(Examples below taken from Didion’s Miami [1987]) This is what I suggested to students:

The following is supposed to be a model of what your submission for this exercise might look like, if you were working on Didion’s book Miami (1987)rather than Salvador. Please note: if you email your reflections to me in WORD format, I will place them into a MediaKron page or PowerPoint for class viewing.

As you can see from the below, for these reflections, you can use the first person, and range around different sources and ideas. Please be sure to put your bibliographical citations inside the body of your own reflections (as they are below). The spirit of this exercise is–

- to offer up material that the class can run with; and

- to be scholarly but also speculative and creative–feel free to “place material” in your reflection even if you’re not quite sue what it means. Even impulsive juxtaposition can have its own rewards!! Thanks.

And so, here’s what your submission might look like:

====================================

__________ [ your name or names]

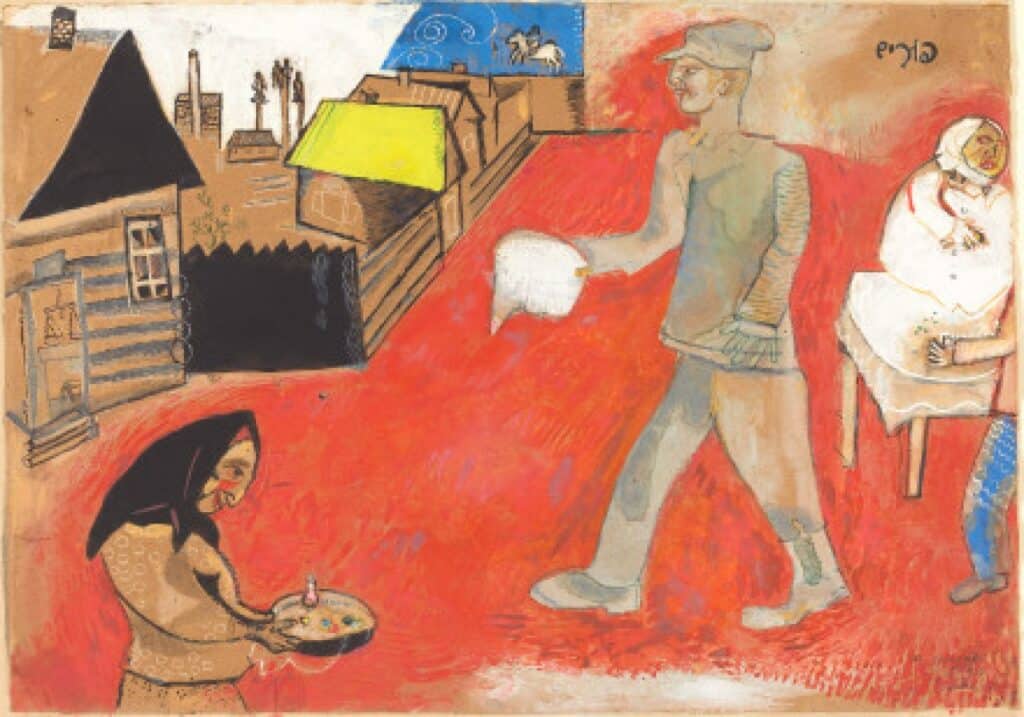

I was [We were} inspired by the references to Marc Chagall in Miami. Although there are many different ways one could make connections to Chagall–Didion talks a lot about “angles” and “bottomless” stories and references dreams several times–I chose to focus on Didion’s apparent interest in the relationships between “dreamscapes,” subjectivity, and proportionality in memory To make this comparison, I [we] chose a painting by Marc Chagall, entitled

Purim,” from 1917. According to scholars Ingo F. Walher and Rainer Metzger, in many of his paintings Chagall chose to use “sectional, sliced images” that “achieve a pictorial unity through the yoking motifs taken from different realms of given reality”–archetypal, geometric, and details from everyday life, like milking cows or dancing–and to juxtapose them in a Cubist way, so that they come to “stand for a reality beyond the visible world, for an imaginative realm in which memories become symbols.” In this way, he creates “an autonomous world dependent on nothing but his own psychology.” (Mark Chagall: Painting as Poetry [N.P.: Barnes and Noble, 1986], p. 20). As Victoria Charles has put it, “[i]n his dreams man often feels himself to be small. Spatial relationships and the proportions of objects are confused” (Marc Chagall, [N.P.: Parkstone International, 2011] p. 75).

I [we] thought our class might compare the above to the following passages from Didion’s Miami:

“There was a flickering all through this presentation of the government’s evidence a certain stubborn irritability, a sense of crossed purposes, crossed wires, of cultures not exactly colliding but glancing off one another, at unpromising angles” (104).========“In this mood Miami seemed not a city at all but a tale, a romance of the tropics, a kind of waking dream. . . Just as any morning could turn lurid, any moment could turn final, again as in a dream.” (34)=========“There was about this account a certain foretold quality, a collapsing of sequence, as in a dream, or an accident report taken from the sole survivor” (112).

I have my own [We have our own] ideas about these passages, but I’ll let the class offer up their own. But I’d/We’d also like to highlight three elements that seem to come out of Didion’s passages:

- complicated ideas about sequencing–that’s what she seems to mean when she speaks of “dreams” or “waking dreams,” or things “foretold”

- ideas about how a mood or a genre can “collapse,” change course;

- and as a result, cultures and personalities that become “angular” and out of control.

===============

So, that’s what a student’s reflection might look like.