A Classroom Exercise on Joan Didion’s Salvador

(Two Different Workshop ideas are actually listed here.)

One of the more intriguing dimensions of Joan Didion’s reportage is the way that it imitates experimental and sometimes postmodern techniques from the visual arts–painting, photography, or architecture, in particular. In many instances, she actually mentions what has inspired her, in a given book, as a clue to how she is re-adapting techniques from these arts to her writerly style. These workshops are about exploring that borrowing.

For instance, in her book about the exile Cuban community in and of Miami (1987), she talks about the exhibition of the performance artist and public sculptor Christo entitled “Surrounded Islands,” in which eleven islands in Biscane Bay were surrounded by millions of acres of floating pink polypropylene fabric, as you can see in the images in the link in the right hand margin here .

Taking her lead from Christo’s art, you might say that Didion herself “surrounds” Miami in seemingly surreal, postmodern effects– where the features of Miami’s landscape, in its art and its local architecture, become clues to its social life and political intrigue. As examples of this “borrowing” from the arts, I have reprinted, below, a couple of selections from Didion’s Miami: one that mentions Christo’s experiment; another that comments on a local architectural firm, and the style of its own building. Altogether, they suggest how Didion is transposing the visual to the textual.

From Miami, on Christo:

“During the time I had spent in Miami many people had mentioned, always as something extraordinary, something I should have seen if I wanted to understand Miami, the Surrounded Islands project executed in Biscayne Bay in 1983 by the Bulgarian artist Christo. . . . It seemed that the pink had shimmered in the water. It seemed that the pink had kept changing color, fading and reemerging with the movement of the water and the clouds and the sun and the night lights. It seemed that this period when the pink was in the water had for many people exactly defined, as the backlit islands and the fluorescent water and the voices at the table were that night defining for me, Miami. (38)

Again, from Miami, talking about the local postmodern architecture:

“A certain liquidity suffused everything about the place. Causeways and bridges and even Brickell Avenue did not stay put but rose and fell, allowing the masts of ships to glide among the marble and glass facades of the unleased office buildings. The buildings themselves seemed to swim free against the sky: there had grown up in Miami during the recent money years an architecture which appeared to have slipped its moorings, a not inappropriate style for a terrain with only a provisional claim on being land at all.

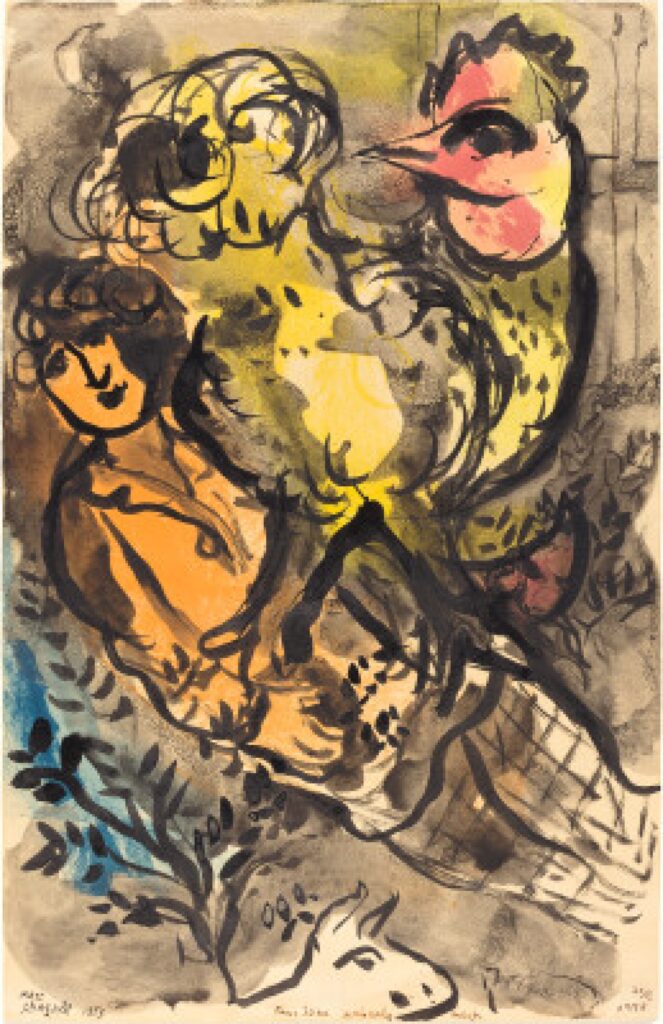

Surfaces were oblique, opalescent. Angles were oblique, intersection to disorienting effects. The Architectonica office, which produced the celebrated glass condominium on Brickell Avenue with the fifty-foot cube cut from its center, the frequently photographed “sky patio” in which there floated a palm tree, a Jacuzzi, and a lipstick-red spiral staircase, accompanied its elevations with crayon sketches, all moons and starry skies and airborne maidens, as in a Chagall.”

View URL

The interesting thing about these “borrowings”, however–and now, connections to Salvador might occur to you–is that these techniques aren’t just about the “look” of Miami. Rather, these reflections also seem to help Didion explore the circulations and “flows” of social life, political power–and the strangely indirect or even oblique way that the citizens of Miami think about or talk about their home city. Thus, also from Miami, a few selected passages, below, talking about the local political context. Try to notice how each of them seems to pick up on the motifs, the imagery, and the settings described above, but tries to apply those techniques to social and political analysis:

On the local political conspiracies involving Cuba and the U.S.:

“There was a flickering through this presentation of the government’s evidence a certain stubborn irritability, a sense of crossed purposes, of cultures not exactly colliding but glancing off one another, at unpromising angles.” (104)

“Local money tended to move on hydraulic verbs: when it was not being washed, it was being diverted, or channeled through Mexico, or turned off in Washington. Local stories tended to turn on underwater plot points, submerged…or fluid connections . . .I recall trying to touch the bottom of one such story . . .” (32)

“In this mood Miami seemed not a city at all but a tale, a romance of the tropics, a kind of waking dream. . . Just as any morning could turn lurid, any moment could turn final, again as in a dream.” (33-34)

“Surfaces tended to dissolve here. Clear days ended less so.” (36)

=============================================

So, here’s your assignment:

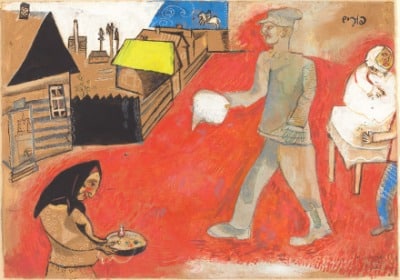

Each student (or pair of students) in these workshops will be assigned the task of drawing similar connections between the visual arts and the book that is in many ways a “prequel” to Miami, Didion’s book Salvador (1983) . From reading this text, you’ll see that Didion explicitly or implicitly calls up two quite different traditions from the visual and plastic arts:

- (A) the conventions of “surrealist” representation (some may think her book title alludes, for instance, to Salvador Dali); and

- (B) the style of Brutalist architecture (sometimes called “The New Brutalism”).

What Each Workshop Entails

Workshop A will be about Didion’s allusions to Surrealism

Workshop B will be about Didion’s Allusions to Brutalist Architecture.

To examine this “borrowing” more closely, each student (or pair of students, if that’s what you prefer) will be responsible for compiling three things:

- An image illustrating one of those two schools of representation (much as I have included the images of Chagall or Miami architecture above)

For workshop A, consider paintings you can find online by Salvador Dali, you might try the Dali Museum-Theatre in Figureres, Spain.

For workshop B, consider images of Brutalist architecture, try these links:

a building at UMass Dartmouth, profiled by the Boston Globe;

a building at Yale, profiled by the New York Times; and

a building in Orange County, California, under dispute, also reviewed by the New York Times. - A quotation (a short paragraph or group of sentences will do) from a scholarly source that clarifies some of the ideas behind that school of representation (see below on recommended sources)

For either of these subjects, use Dali or “Brutalism” in books.google.com. Or, you can go to your school’s library and try the database links there.

On Brutalist architecture, you can try the Avery Index to Architectural Periodicals. (like books.google.com or scholar.google.com, or the web more generally. - and a set of short passages or groups of lines from Salvador that invites a provocative comparison to what the image or the quotation suggest is characteristic of the style, and the uses to which Didion is putting it. I’d also like you to reflect, informally, on what techniques or ideas the comparison suggested to you.

You can see a sample of what a submission might look like by using the link on the main “Resources for Teachers” page.