Understanding Modes and Discourses

“What is Art, but a Way of Seeing?” –Saul Bellow

It’s also helpful, when you’re thinking about Genre and literary appropriations of conventions, to think about the narrative modes that it uses. Essentially, a mode is a constellation of stylistic effects that combine together to elicit a familiar set of responses in readers. Rather than thinking of them as a recipe that a journalist “fills in,” it’s more useful to think of them as “gears” writers shift into. (Typical modes, for instance, are the “sentimental,” the “melodramatic,” the “sensational” and so on. (Click here to see a useful checklist.) Thus a mode may appear only for part of that text, or may coexist with other modes in the same text. So a stand-alone article might be called a “profile.” But “profiling” can also be a mode inside a longer piece.

A mode is sometimes said to be both a set of literary techniques and a “knowledge of reality” behind a text.1 To say Riis’s How the Other Half Lives is Dickensian, again, is not to say that Dickens is being imitated in a rote sort of way. Rather, we’re describing Dickensian moments or phases when a journalist moves into a recognizable or trademark way of writing and seeing, again sending cues to readers about how they might respond.

Take, for instance, the following well-known moment from Riis’s How the Other Half Lives, in which the reporter recreates a visit to a tenement house. It helps to know that Riis often read passages like these out loud, when he was giving his famous public lectures on poverty, taking his listeners on a kind of tour of the slums complete with sound effects and even reenactments of city scenes. Here, he takes them into a tenement:

Suppose we look into one? No. — Cherry Street. Be a little careful, please! The hall is dark and you might stumble over the children pitching pennies back there. Not that it would hurt them; kicks and cuffs are their daily diet. They have little else. Here where the hall turns and dives into utter darkness is a step, and another, another. A flight of stairs. You can feel your way, if you cannot see it. Close? Yes! What would you have? All the fresh air that ever enters these stairs comes from the hall-door that is forever slamming, and from the windows of dark bedrooms that in turn receive from the stairs their sole supply of the elements God meant to be free. . . . Here is a door. Listen! That short hacking cough, that tiny, helpless wail—what do they mean? They mean that the soiled bow of white you saw on the door downstairs will have another story to tell—Oh! a sadly familiar story—before the day is at an end. The child is dying with measles. With half a chance it might have lived; but it had none. That dark bedroom killed it.

“It was took all of a suddint,” says the mother, smoothing the throbbing little body with trembling hands. There is no unkindness in the rough voice of the man in the jumper, who sits by the window grimly smoking a clay pipe, with the little life ebbing out in his sight, bitter as his words sound: “Hush, Mary! If we cannot keep the baby, need we complain—such as we?”

Here again, we see the Dickensian effects I mentioned earlier: the direct appeal to sentiment, again through the death of a child; a strong, evocative narrator offering a powerful indictment of the greed that denies the poor the fresh air “God meant to be free”; the breeding of bitterness and disillusionment in the poor. In the passage above, in fact, Riis seems to be willfully inventing a “what if” scene for his audience’s virtual tour—that is, creating an imaginary journey for his listeners that he probably went on, many times. The Dickensian mode Riis uses asks readers to respond to his reporting not merely as news in the informational sense, but as something with which they might engage their sympathy, empathy, imagination.

That’s what a mode is about: it’s not just a way of seeing poverty but a way of feeling about it, too, too. It is even in the intentional pun Riis uses: as he puts it, his readers are asked to “feel” their way into the tenements. His resorting to direct address (another familiar element in the Dickensian mode) calls out to them, and calls them out. In this sense, then, the scene’s use of a Dickensian literary mode has interpretive power and authority. Readers are asked to picture a world in which particular cases of spiritual suffering might be alleviated by the patronage of a free individual enacting their sentiment for the larger public good. To his own contemporaneous audience, being Dickensian in this scene signaled the humane sensibility Riis was both performing—becoming, as it were, that patron that had once saved him from a similar fate—and asking them to become.

It’s also important, however, to see that this Dickensian mode is only part of Riis’s overall strategy—in fact, he is mixing different modes to enhance the emotional impact and authority of what he writes and photographs. For instance, some scholars have recently suggested that a scene like the one above was often regarded as a Christian parable of sorts, that asked Riis’s readers to see through the material world to its spiritual essence. It was a timeless tale they would recognize form the Bible (a mother named Mary, after all, and a child with no place to sleep).You can see that kind of representation in the “Madonna”-like sketch that patterned itself after one of Riis’ photographs:2]

But that’s only one of the modes that may be at work here. On top of that, the passage above also makes use of modes developed in the story-form of the urban tour or travel narrative of the mid-nineteenth century. This mode had been part of a long tradition of journalistic sketch work of the city that had appeared in newspapers and reform texts for a long time. The signature effect was that of a narrator who was a knowledgeable walker in a city who directly addresses an innocent reader who accompanies him through the alleys and byways of urban locations and undergrounds. Versions of this story-form were commonplace in the so-called “Sunlight and Shadows” narratives of the 1870s and 1880s, and had been developed earlier by reporters like George Foster, author of New York by Gas-Light (1850). Here’s a passage from Foster’s work that applies the mode of the underground voyage into a labyrinth of darkness that only the criminal can pretend to know:

So, then, we are standing at midnight in the center of the Five Points. Over our heads is a large gas-lamp, which throws a strong light for some distance around, over a scene where once complete darkness furnished almost absolute security and escape to the pursued thief and felon, familiar with every step and knowing the exits and entrance to every house .. [with each room only] a little less gloomy and terrible than the grave itself, to which it is the prelude.

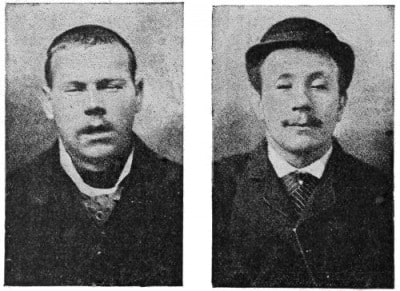

In addition to following a writer like Foster, however, Riis was also tapping into quite contemporary ways of thinking that were outside traditional literary or journalistic traditions per se. Because he actually walked the city in the company of charity workers, police officers, and health department officials, Riis’s published text thus drew on the ways of seeing and interpreting that such new forms of social control, public management, and data-collection entailed. In fact, as you can see from the paired photographs below, Riis’s photographs of street gang members paralleled the emergence of galleries of criminals that you can find, for example, in one of the most popular crime books in the late 19th century, Professional Criminals of America, written by the New York Police department’s chief investigator Thomas J. Byrnes. Such galleries were not only used to keep track of local criminals, but to apply the Victorian pseudo-science of anthropometrics (that is, the measurement of physical features) as a way to classify criminals by type:

Visual modes appeared, as well, not only in the photographs or sketches Riis included. How the Other Half Lives has charts like the one you see below, again drawing on social-science modes of explanation:

In other words, if the Dickensian mode of How the Other Half Lives called up sentiment and notions of charity, Riis blended it with the originally Utilitarian practices of charity reformers who had been, at least since Henry Mayhew’s London Labour and the London Poor (1840/1851), documenting the lives of the disadvantaged en masse. That is, these ways of seeing had in many ways built our modern conception of “the poor” as people to be measured in the aggregate, assessed for their demographic statistical profile (as, here, in birth and death rates). A similar strategy is evident in Ida B. Wells’s Red Record (1896), in which Wells might be said to have “patched together” accounts of lynching from other newspapers. But her strategy, of course, was to use the authority of white newspapers and their editors–that was how her statistics gathered force. In other words, such modes of journalistic story-telling also drew upon the authority of interpretive powers outside recognized literary genres or modes. That is, they drew upon aspects of ways of writing and thinking that have been developed in academic disciplines like anthropology, History, or psychology, or in professional practices like policing, public health or medicine. The critical term we often use for these ways of thinking is discourses: a term we might define as the systematic ways of thinking, interpreting, and writing that characterize a particular field of formal inquiry.

As How the Other Half Lives shows, material from such discourses, of course, can appear in narrative journalism very nearly “as is”—that is, cited or quoted directly, as forms of expertise that inform a given storyline. For example, a journalist might pause to cite recent research from brain science or anthropological studies of a given subculture; indeed, in many cases, long-form feature writing can be built around reporting on such discoveries, as the reporter will explain in the conventional “nut graph” paragraph or moment in their article. Indeed, conventional forms of reporting surrounding legal case use the courtroom as a pretext for introducing such testimony, and allowing the larger debates within a given field of inquiry to grow, accordingly. As New Yorker reporter Calvin Trillin once put it, journalists are almost “always working in someone else’s field of expertise” (as qtd. Boynton, 390) That, again, is using a discourse. And the truth of it is that even the most formal of professional discourses also have their own conventions, modes, and ways of seeing—their own ways of casting and interpreting characters, describing cause and effect, drawing conclusions and so forth.