Conventions, Modes and Discourses in Journalistic Story-Telling

Guiding Questions for This Chapter

What does it mean to say that journalists draw upon literary conventions?—that is, upon specific story-forms that we associate with fiction? What, for instance, would it mean to say a reporter writing about poverty is working in a “Dickensian” style? How does borrowing from the conventions and discourses of literary genres affect the authority of a work of narrative journalism?

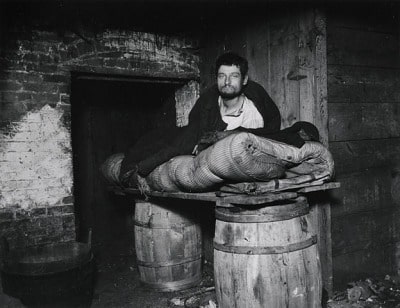

One of the more intriguing episodes in U.S. journalism history takes place in How the Other Half Lives (1889), the exposé by the famous 19th-century reporter and photographer, Jacob Riis. Riis’s photographs have become nearly iconic in the history of American journalism–markers of the emergence of documentary reporting:

Riis himself had suffered extreme poverty, early in life. In fact, in his autobiographyThe Making of an American (1901), he recounted how, in his early years as a recently-arrived Danish immigrant, out of work and without a trade, he had slept on the streets of New York City. Wandering around the metropolis begging and looking for work, he had also picked up, as a companion, a small dog that he had affectionately named “Bob”–who, he tells us, “could always coax a supper out of the servant at the basement gate” by doing jumps and tricks, “while I pleaded vainly and hungrily with the mistress at the front door” (119).

To fight off starvation, Riis had even “taken to peddling books” (119), in particular trying to sell an illustrated copy of Charles Dickens’s Hard Times (1853), the famous reform novel about the dreary lives of factory workers in industrial-era England. Riis had assumed that, triggered by the famous story of the book, potential buyers would react sympathetically to his own plight, and offer help. But even Dickens’s classic seemed to do no good:

Two days without food is not good preparation for a day’s canvassing. We did the best we could. Bob stood by and wagged his tail persuasively while I did the talking; but luck was dead against us, and “Hard Times” stuck to us for all we tried . . . Faint with hunger, I sat down on the steps under the illuminated clock [of the Cooper Institute], while Bob stretched himself at my feet. . . . Tomorrow there was another day of starvation. How long was this to last? Was it any use to keep up the struggle so hopeless? . . . I was bankrupt in hope and purpose. Nothing had gone right; nothing would ever go right; and, worse, I did not care. . . . My life was wasted, utterly wasted (120-121).

But then, miraculously, the two were saved from desperation by a principal from a telegraph school that Riis had previously attended. Telling Riis that selling books was never going to make him rich, the man instead asked him if he would instead like a job as a reporter with a local news agency. And thus, “[a]s in a dream,” Riis was launched upon his famous career. Looking back decades later, the reporter took time to underscore the larger forces at work in his patron’s gesture: ” . . . I saw a hand held out to save me from wreck, just when it seemed inevitable,” Riis would write in his autobiography, “and I knew it for [God’s] hand . . . I bowed my head . . . and prayed for the strength to do the work which I had so long and arduously sought” (123). (Bob, incidentally, was deposited in a proper Christian home while Riis started up with his new employer.)

One might say many things about this particular memory. But perhaps the most relevant point, here, is how thoroughly literary—or, in fact, how completely “Dickensian”–Riis had made this episode in his autobiography. The memory betrays many trademark elements of a Dickens novel: for instance, the very moment the world of poverty had threatened to crush our hero’s hopes and spirits, the benevolent hand of another individual, acting out of simple charity, enacts the humane obligations of a secularized Christian ethos. Poverty is in fact seen by Riis, as it had been by Dickens, as predominantly a spiritual matter, less a matter of exploitation than an experience of hopelessness and despair. His patron’s aid models an instinctual understanding of human needs; even the dog Bob, a symbol of that instinctual spirit of love, provides another recognizable Dickensian touch. Riis also suggests the immigrants will eventually learn how to take their turn in this chain of benevolence—in essence, they will become Americans that way. Riis not only adapts the stylistic tools Dickens used, but the social philosophy behind them. And because much of Riis’s audience made those same associations, citing or using Dickens meant tapping into his readers’ belief-system as well. In this sense, you might think of using a genre as akin to connecting into the warm feelings, the legitimacy, and even the explanatory power that readers associated with Dickens’s work. Or, in other words, plugging into what we call its authority.1

Genre, in fact—the term we generally use for a specific type or category of literature marked by shared features or conventions–is often a word that often comes into play when we begin talking about such literary inheritances. As we’ve already seen in previous Chapters, Hersey borrowed from Thornton Wilder’s Bridge of San Luis Rey, just as Kotlowitz did from Dickens, too. Barbara Ehrenreich, likewise, might be seen as an inheritor of techniques pioneered by Riis himself, and even more by one of his contemporaries, Nellie Bly. This is why you’ll often find commentators refer to literary or narrative journalism as a “border crossing” mode of writing, or a “blurred genre”—that is, a way of writing that blends or hybridizes journalistic approaches with literary techniques. That is also why audiences, it is sometimes argued, find narrative journalism so engaging.

In this chapter, I’m going to lay out different ways to think about Genre as a fruitful concept for understanding the various “story-forms” of narrative journalism. So, in essence, what we’re doing here is deepening the discussions in Chapters 2 and 3–now we’re talking about other ways to understand the dimension of “the story” that not only makes a work of narrative journalism entertaining or “powerful,” but something we accept as authoritative.

I’m also going to suggest that it’s a bit more productive to think about genre in three more specific ways– what I will be calling the conventions, modes, and discourses that journalists call upon. And I’m going to finish the Chapter by discussing a terrific narrative journalist, Ann Fadiman, who “mixes” these modes in one piece of writing. That’s because she shows us that using a genre isn’t simply for “literary” power–it’s also about calling up the interpretive authority of what we read. For it turns out that sometimes, in fact, narrative journalists may even pick a tool or a passage that, strictly speaking, wasn’t “literary” in its original form, at all. Rather, they can plug into the authority of other ways of thinking or writing in their society. In either case, however, genre matters for narrative journalism a great deal, indeed.

Resistances to Mixing Journalism and Literature

By and large, as I’ve said, scholars use the term “genre” to point to the fact that story-forms fall into types, But these can be different kinds of literary borrowing:

- Again, writers of narrative journalism have been known to imitate specific novels well known for their experimentalism and power: George Packer has recently re-tooled the panoramic, collage effects of John Dos Passos’s USA trilogy to describe The Unwinding (2013) of social and political authority in the post-Iraq U.S. In 2002, returning foreign correspondent Philip Gourevitch adapted the “case file” approach of the procedural mystery, made famous by fiction writers like Ed McBain, to a nonfiction modern murder story in A Cold Case (2001).

- types determined by plot patterns, the appearance of certain characters, even signature ways of talking to readers. For instance, contemporary portraits of prostitution or sex trafficking often call up genre patterns extending back as far as Daniel Defoe’s Moll Flanders (1722), or Stephen Crane’s “Maggie A Girl of the Streets” (1893). Journalistic exposés of organized crime, like Peter Maas’s Serpico (1968) or Nicholas Pileggi’s Wise Guy (1985) reveal debts, conscious and otherwise, to 19th-century portraits of street urchins and criminals, and even the heroes of Horatio Alger; Barbara Ehrenreich, as I’ve suggested, has drawn on elements of the picaresque tradition.

Indeed, even some of the strongest defenders of narrative news writing these days will deny that there is any “gap” at all between what you report, and the story-form you choose to tell: that kind of transparency is, they say, the hallmark of good journalism.2

However, as you may know, you can also easily find voices in the journalism profession itself who have distrusted the very idea of introducing literariness into so-called “hard” news. Editors often tell young writers that if they want to write stories in a literary sense, they are better off sticking to recognized sub-genres from the field itself (like the immersion story or the profile.) (I will say more about the genre of the profile below). Some will argue that the application of a particular set of conventions to a given story can undermine solid reporting. When Susan Sheehan has used the New Yorker profile style for portraits of the poor or the criminal, for instance, she has won wide acclaim. But some readers and reviewers have taken her to task, finding that the condescension and “clinical” snobbery of the magazine bleeds into her picturing. And so forth.3

Meanwhile, you don’t have to look very far to find even accomplished narrative journalists bristling at the very idea they are bound by the genre conventions of the past. Their logic often goes like this: if a reporter’s primary goal is to “get the story,” in the news-content, empiricist sense I outlined in Chapter 2, then why should a given set of facts that reporter uncovers conform to literary conventions at all? Shouldn’t that set of facts, by definition, follow its own patterns? And so you can find very fine writers saying, for instance, that they’re not doing an “undercover” expedition in the traditional sense, or not writing a “muckraking” exposé even when it seems like they are.4 It’s as if they realize someone is out there ready to discount them for being too “literary.”

Looking at one well-recognized journalistic genre—political travel correspondence–might indicate the double bind narrative journalists can find themselves in. As the name itself suggests, travel (and even some war) correspondents were, in the mid-nineteenth century, letter-writers: before the advent of the telegraph, such a person might be a temporary resident of a foreign country, a diplomat stationed there, even a soldier, who wrote longer, reflective pieces and sent them back to American newspapers and magazines. In print, the format was very much that of a traveling lecture, a format that even Riis was echoing when he used lantern-slide presentations to exhibit his photographs. (Riis in fact refers to himself as something of a “war correspondent” [How The Other Half Lives, 71]). And as the conventions of the travel-correspondent genre developed, the customary functions of such a figure were that he (typically he) should measure his host country’s capacity for democratic governance—in more heroic and jingoistic veins, the correspondent often cast himself as the representative of that ethos—and, often just as overtly, to measure the natural resources suitable for economic development, obviously not just by the locals but by his home (U.S.) audience. As Mary Louise Pratt has shown, the conventional panoramic vista offered by the travel writer implicitly encoded an elite distance and removal from the social and political turmoil on the ground—and, if it is not obvious, racism, paternalism, and exoticism were the rule of the day, not the exception.5 And perhaps also needless to say, traveling with American armies—following, that is, another set of conventions that put empathy with soldiers at a premium—might easily reinforce the conventional hierarchies and myopia of the genre supposedly devoted to assessing a country’s suitability for “development” even more.

Now, given all that baggage, you can imagine why a contemporary journalist might well be likely to disown the genre form altogether—and many successfully do. Some, like Joan Didion in Salvador, may try to parody the idea of a nortamericano observer who has no way of understanding El Salvador’s violent chaos (see my discussion of Didion in Chapter 5); others, like Dexter Filkins in Iraq, try to engage and honor the forces of democratic sovereignty within the indigenous population, rather than just writing about American soldiers; some like Philip Rieff writing on Los Angeles, may invert the traditional hierarchy and claim this U.S. city is now the “capital” (his pun intended) of so-called Third World. But even though writers of reportage do push back against the weak spots of their inherited conventions, the interpretive work we do as readers often asks us to consider whether these escape routes are fully successful. Or, instead, whether reporters fall victim to the perils of a pack mentality or parachute journalism, which reinforces the practice of quick-hit visits by journalists not immersed (or embedded) at all, and thus falling back on threadbare genre forms. Indeed, in these moments genre itself seems less like an interpretive tool and more like—well, like flypaper.

So how do we adjust our thinking on these subjects?—since, once again, I’d insist on three points:

- First, that you might be better thinking about genre as a set of inheritances or tools–former ways of writing–that are modified or readapted to new social or political conditions. That is, isn’t just about the story-form being “re-used.” It’s about it being changed (and, as we’ll see, sometimes blended with other genres in new ways.

- Therefore, some of the best narrative journalists don’t just “adopt” a genre and apply it in a rote fashion; indeed, sometimes the best adaptations can be those that know the rules but subtly depart from them.

- And furthermore, that what really matters for you as a reader is mixing empathy and critique: you try to “get into the head” of the writer and see how such genre conventions have been revised–in other words, why the reporter used those . And then, as you assess as how such inheritances have shaped the interpretive work that a work of narrative journalism does, you look for “how well” it’s done. (See some exercises in this technique here).

What other tools, in short, can we discover that help us figure out, more substantively, how adapting more recognizably literary conventions shapes a given journalists’ work?

Being More Precise about Genre

First of all, it’s helpful to recognize that genre turns out to actually be contingent upon smaller, more specific elements–what we call conventions, or the parts that make up the whole. We call these literary devices “conventions” because they have acquired importance, primarily in establishing expectations in readers. These expectations may be not just about stylistic elements, but about the proper emotional response, or the worldview, implicitly encoded in the convention.

In some ways, it’s helpful to think about these conventions a a bit like ingredients in a given Genre’s recipe: it really depends on how much of them are applied, and what they are mixed into. In fact, conventions can cross over from one genre to another–and when they do, they can be used to different ends. For instance, fairy tales conventionally begin with a young child who has been orphaned or abandoned—a story-pattern that one finds reapparing in the nineteenth-century sentimental novel, and also narrative journalism about today’s foster care system. Modern hard-boiled detective mysteries often used the convention a “crime under the crime”—that is, a larger pattern of social or political corruption that is revealed when a detective starts out thinking they are merely solving a murder. That convention reappears in journalistic exposés, too.

Conventions aren’t only about plot patterns, too:

- Sometimes conventions can be matters of narrative voice—the sentimental novel, for instance, often used “direct address” to the reader (called out to with a “you”). (Think about how important this is to today’s podcast or digital journalism.

- Sometimes it can be about how the narrative pattern shapes the architecture of the text as a whole. For instance, in journalism about the city in the 19th century,the urban world is often divided into two halves, upper and lower, with the latter being described a labyrinth or maze). Writers of exposés like Riis, Crane, Bly and Jack London in fact established a convention based on that idea.

- It can be a convention about how reporters themselves are described: in exposé, it’s not uncommonly a story of the heroic reporter who seems to dive down into the world of the “lower half,” as writers like Ehrenreich, William Vollman, and so many others have. And as I’ve suggested in Chapter 3, certain story-form conventions re-adapt the idea of the “crossing over” as the entry into another world or country; the writer’s sense of dislocation or disorientation, especially in the loss of one’s upper-world identity and skills; the fears of drowning, having one’s body inundated or overcome; the crossing back across the social threshold, and the feeling one is “saved” but also marked—and more.

One could certainly list dozens of other journalistic conventions that have shaped different journalistic genres . Just think how many times you’ve read the news story that uses a struggling family as a microcosm of failures in the welfare system, or that uses a murder trial as an entrée into a particular city or region, or interviews celebrities as they plays out the string at the end of a career. These are templates for “story-forms” that may well have originated in literary stories but have come to inhabit the journalism trade for some time.

But as I’ve already suggested, conventions are modified over time: writers break rules and readapt the form they’ve been using–and, if you understand what I mean, you have a new set of conventions that subsequent journalists will work with.

Take the example of the “profile,” a genre term thought to be invented by the staff of The New Yorker in its early years. While today we tend to use the term “profile” to refer to an intensive, detailed, deeply nuanced biographical portrait. Yet in fact originally in The New Yorker the word reflected a parallel idea in the visual arts: the profile was literally a sideways view, as in a sketch or pencil drawing. Back then, New Yorker editors actually wanted a portrait in writing that was less than three-dimensional, more oblique and ironic and even light hearted. That is, the mode was originally more comic, brisk and metropolitan, focusing on the idiosyncrasies of Manhattan personalities. Only in the late 1930s did what we assume is the trademark form, the “accumulating” of fact upon fact, come into being. By then, as Ben Yagoda has put it, “as if the writer were continually circulating around the subject” until arriving at something like the three-dimensional study we would recognize now[1] (137). Yagoda also tells us that John Hersey, tired of the upper-class tone of the metropolitan observer and man-about-town, asked his editor if he could do a “fly on the wall” version in which his own presence was not discernible–a choice that partly led to the style of Hiroshima (Yagoda 251). Later still, editors would urge Lillian Ross or Rachel Carson or Calvin Trillin to break out of the biographical mode itself, and apply the “profile” idea to the motion picture industry, to the natural world, or to small-towns in the Midwest—or, even later, in Susan Sheehan’s case, to a schizophrenic or a prisoner or a welfare recipient.

As I’m sure you know, writing a work of narrative journalism isn’t like baking a cake, with the reporter just adding in the literary ingredients–as if these literary designs are mere “flavoring.” Rather, as I’ve suggested in my opening about Jacob Riis, these changing conventions carry interpretive weight with audiences–as it were, the power to explain the world for readers.

Understanding Modes and Discourses

“What is Art, but a Way of Seeing?” –Saul Bellow

It’s also helpful, when you’re thinking about Genre and literary appropriations of conventions, to think about the narrative modes that it uses. Essentially, a mode is a constellation of stylistic effects that combine together to elicit a familiar set of responses in readers. Rather than thinking of them as a recipe that a journalist “fills in,” it’s more useful to think of them as “gears” writers shift into. (Typical modes, for instance, are the “sentimental,” the “melodramatic,” the “sensational” and so on. (Click here to see a useful checklist.) Thus a mode may appear only for part of that text, or may coexist with other modes in the same text. So a stand-alone article might be called a “profile.” But “profiling” can also be a mode inside a longer piece.

A mode is sometimes said to be both a set of literary techniques and a “knowledge of reality” behind a text.6 To say Riis’s How the Other Half Lives is Dickensian, again, is not to say that Dickens is being imitated in a rote sort of way. Rather, we’re describing Dickensian moments or phases when a journalist moves into a recognizable or trademark way of writing and seeing, again sending cues to readers about how they might respond.

Take, for instance, the following well-known moment from Riis’s How the Other Half Lives, in which the reporter recreates a visit to a tenement house. It helps to know that Riis often read passages like these out loud, when he was giving his famous public lectures on poverty, taking his listeners on a kind of tour of the slums complete with sound effects and even reenactments of city scenes. Here, he takes them into a tenement:

Suppose we look into one? No. — Cherry Street. Be a little careful, please! The hall is dark and you might stumble over the children pitching pennies back there. Not that it would hurt them; kicks and cuffs are their daily diet. They have little else. Here where the hall turns and dives into utter darkness is a step, and another, another. A flight of stairs. You can feel your way, if you cannot see it. Close? Yes! What would you have? All the fresh air that ever enters these stairs comes from the hall-door that is forever slamming, and from the windows of dark bedrooms that in turn receive from the stairs their sole supply of the elements God meant to be free. . . . Here is a door. Listen! That short hacking cough, that tiny, helpless wail—what do they mean? They mean that the soiled bow of white you saw on the door downstairs will have another story to tell—Oh! a sadly familiar story—before the day is at an end. The child is dying with measles. With half a chance it might have lived; but it had none. That dark bedroom killed it.

“It was took all of a suddint,” says the mother, smoothing the throbbing little body with trembling hands. There is no unkindness in the rough voice of the man in the jumper, who sits by the window grimly smoking a clay pipe, with the little life ebbing out in his sight, bitter as his words sound: “Hush, Mary! If we cannot keep the baby, need we complain—such as we?”

Here again, we see the Dickensian effects I mentioned earlier: the direct appeal to sentiment, again through the death of a child; a strong, evocative narrator offering a powerful indictment of the greed that denies the poor the fresh air “God meant to be free”; the breeding of bitterness and disillusionment in the poor. In the passage above, in fact, Riis seems to be willfully inventing a “what if” scene for his audience’s virtual tour—that is, creating an imaginary journey for his listeners that he probably went on, many times. The Dickensian mode Riis uses asks readers to respond to his reporting not merely as news in the informational sense, but as something with which they might engage their sympathy, empathy, imagination.

That’s what a mode is about: it’s not just a way of seeing poverty but a way of feeling about it, too, too. It is even in the intentional pun Riis uses: as he puts it, his readers are asked to “feel” their way into the tenements. His resorting to direct address (another familiar element in the Dickensian mode) calls out to them, and calls them out. In this sense, then, the scene’s use of a Dickensian literary mode has interpretive power and authority. Readers are asked to picture a world in which particular cases of spiritual suffering might be alleviated by the patronage of a free individual enacting their sentiment for the larger public good. To his own contemporaneous audience, being Dickensian in this scene signaled the humane sensibility Riis was both performing—becoming, as it were, that patron that had once saved him from a similar fate—and asking them to become.

It’s also important, however, to see that this Dickensian mode is only part of Riis’s overall strategy—in fact, he is mixing different modes to enhance the emotional impact and authority of what he writes and photographs. For instance, some scholars have recently suggested that a scene like the one above was often regarded as a Christian parable of sorts, that asked Riis’s readers to see through the material world to its spiritual essence. It was a timeless tale they would recognize form the Bible (a mother named Mary, after all, and a child with no place to sleep).You can see that kind of representation in the “Madonna”-like sketch that patterned itself after one of Riis’ photographs:7]

But that’s only one of the modes that may be at work here. On top of that, the passage above also makes use of modes developed in the story-form of the urban tour or travel narrative of the mid-nineteenth century. This mode had been part of a long tradition of journalistic sketch work of the city that had appeared in newspapers and reform texts for a long time. The signature effect was that of a narrator who was a knowledgeable walker in a city who directly addresses an innocent reader who accompanies him through the alleys and byways of urban locations and undergrounds. Versions of this story-form were commonplace in the so-called “Sunlight and Shadows” narratives of the 1870s and 1880s, and had been developed earlier by reporters like George Foster, author of New York by Gas-Light (1850). Here’s a passage from Foster’s work that applies the mode of the underground voyage into a labyrinth of darkness that only the criminal can pretend to know:

So, then, we are standing at midnight in the center of the Five Points. Over our heads is a large gas-lamp, which throws a strong light for some distance around, over a scene where once complete darkness furnished almost absolute security and escape to the pursued thief and felon, familiar with every step and knowing the exits and entrance to every house .. [with each room only] a little less gloomy and terrible than the grave itself, to which it is the prelude.

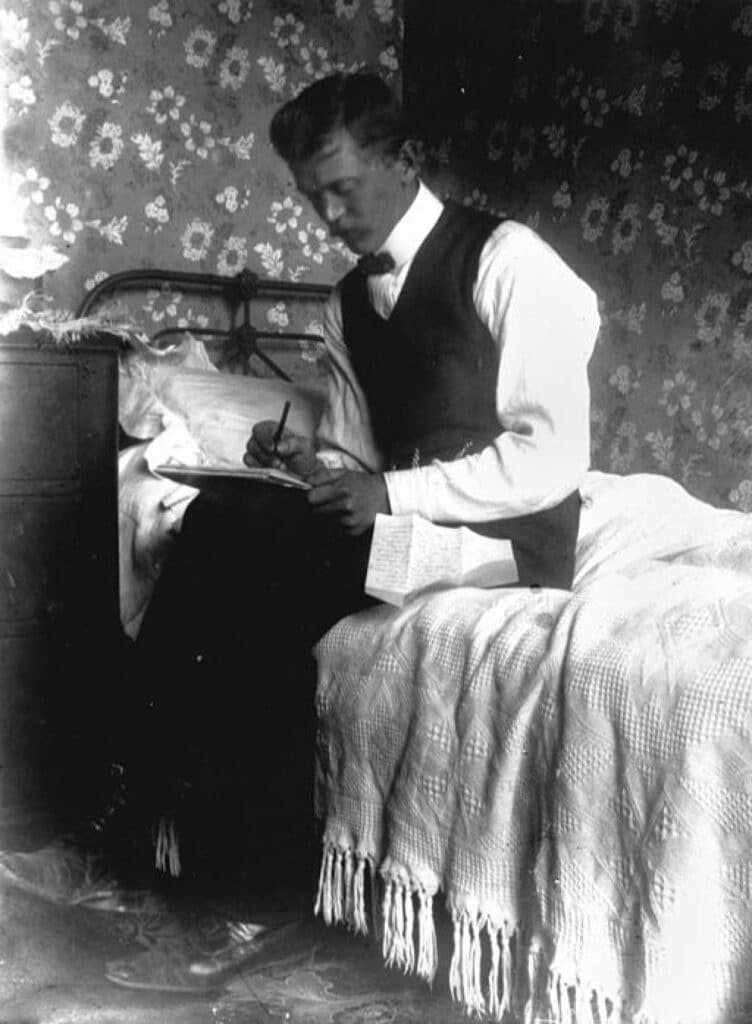

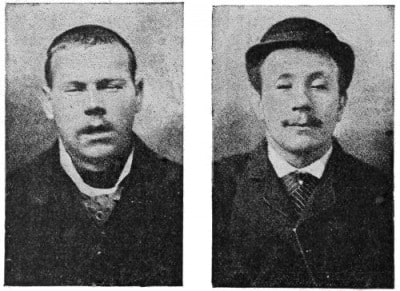

In addition to following a writer like Foster, however, Riis was also tapping into quite contemporary ways of thinking that were outside traditional literary or journalistic traditions per se. Because he actually walked the city in the company of charity workers, police officers, and health department officials, Riis’s published text thus drew on the ways of seeing and interpreting that such new forms of social control, public management, and data-collection entailed. In fact, as you can see from the paired photographs below, Riis’s photographs of street gang members paralleled the emergence of galleries of criminals that you can find, for example, in one of the most popular crime books in the late 19th century, Professional Criminals of America, written by the New York Police department’s chief investigator Thomas J. Byrnes. Such galleries were not only used to keep track of local criminals, but to apply the Victorian pseudo-science of anthropometrics (that is, the measurement of physical features) as a way to classify criminals by type:

Visual modes appeared, as well, not only in the photographs or sketches Riis included. How the Other Half Lives has charts like the one you see below, again drawing on social-science modes of explanation:

In other words, if the Dickensian mode of How the Other Half Lives called up sentiment and notions of charity, Riis blended it with the originally Utilitarian practices of charity reformers who had been, at least since Henry Mayhew’s London Labour and the London Poor (1840/1851), documenting the lives of the disadvantaged en masse. That is, these ways of seeing had in many ways built our modern conception of “the poor” as people to be measured in the aggregate, assessed for their demographic statistical profile (as, here, in birth and death rates). A similar strategy is evident in Ida B. Wells’s Red Record (1896), in which Wells might be said to have “patched together” accounts of lynching from other newspapers. But her strategy, of course, was to use the authority of white newspapers and their editors–that was how her statistics gathered force. In other words, such modes of journalistic story-telling also drew upon the authority of interpretive powers outside recognized literary genres or modes. That is, they drew upon aspects of ways of writing and thinking that have been developed in academic disciplines like anthropology, History, or psychology, or in professional practices like policing, public health or medicine. The critical term we often use for these ways of thinking is discourses: a term we might define as the systematic ways of thinking, interpreting, and writing that characterize a particular field of formal inquiry.

As How the Other Half Lives shows, material from such discourses, of course, can appear in narrative journalism very nearly “as is”—that is, cited or quoted directly, as forms of expertise that inform a given storyline. For example, a journalist might pause to cite recent research from brain science or anthropological studies of a given subculture; indeed, in many cases, long-form feature writing can be built around reporting on such discoveries, as the reporter will explain in the conventional “nut graph” paragraph or moment in their article. Indeed, conventional forms of reporting surrounding legal case use the courtroom as a pretext for introducing such testimony, and allowing the larger debates within a given field of inquiry to grow, accordingly. As New Yorker reporter Calvin Trillin once put it, journalists are almost “always working in someone else’s field of expertise” (as qtd. Boynton, 390) That, again, is using a discourse. And the truth of it is that even the most formal of professional discourses also have their own conventions, modes, and ways of seeing—their own ways of casting and interpreting characters, describing cause and effect, drawing conclusions and so forth.

The Example of Anne Fadiman

In fact, that last idea is connected to what I mean to highlight to close this Chapter. I want to explore what happens when a reporter does more than quote experts in a given field. Rather, I want to turn to those moments when a journalist shifts the very substance of their own story-telling into these other, extra-literary discourses.

Let’s imagine, say, a hypothetical traffic accident–and 3 different people who arrive after it. What will they do?

- If a Good Samaritan doctor arrives on the scene, typically they will treat the drivers of the cars as if they are injured patients, and ask them a set of questions to see if and where they are hurt or in shock;

- But if a lawyer comes upon the same accident, they will very likely begin to advise the drivers about what to say and what not to;

- A police officer, finally, will act differently from both doctors and lawyers, perhaps taking everyone’s account of the crime, measuring distances and skid marks, re-directing traffic around the accident, and so on.

Now, it’s the same scene to all of them—but they see it, interpret, and write it up in completely different ways. And that’s because, working as professionals in different fields, they’ve been trained to use the vocabularies and techniques that define those fields–their discourses. (The same thing can happen to you when you write a paper for a different course in a different discipline.)

To illustrate how this can happen in a work of narrative journalism, I’m going to list, below, four different passages from a brilliant, prize-winning work of narrative journalism, Anne Fadiman’s The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down (1997). In Fadiman’s case–rather than just using one discipline’s “lens”–it’s a bit more like what is called a Phoropter, above–that is, the device in which we are asked to shift through different lens to align a “total” precise vision. Sometimes when a reporter shifts between discourses, it’s as if they’re flipping through different lenses.

At its core, Fadiman’s book concerns a very tragic medical case involving the daughter of a refugee couple of Hmong descent, spouses named Fao Kao and Foua Lee, who migrated with their children to the United States after the Vietnam war. They have just arrived in Merced, California, when their daughter Lia begins to develop symptoms of epilepsy, and the family turns to a local community hospital for help–and where, soon, just about everything goes wrong. Below are the four passages—from different phases of the book, in sequence. I’ll provide brief introductions for each.

First, a passage from the opening of the book, describing the culture of the Hmong people, and in particular their views of childbirth:

. . . no Hmong woman of childbearing age would ever think of setting foot inside a cave, because a particularly unpleasant kind of dab [spirit] sometimes lived there who liked to eat flesh and drink blood and could make his victim sterile by having sexual intercourse with her. Once a Hmong woman became pregnant, she could ensure the health of her child by paying close attention to her food cravings. If she craved ginger and failed to eat it, her child would be born with an extra finger or toe. If she craved chicken flesh and did not eat it, her child would have a blemish near its ear. . . When a Hmong woman felt the first pangs of labor, she would hurry home from the rice or opium fields, where she continued to work throughout her pregnancy. It was important to reach her own house, or at least the house of one of her husband’s cousins, because if she gave birth anywhere else a dab might injure her. (4)

Then, later, a passage where we begin to see what adjusting to America does to the self-esteem of Hmong the mother we’ve been following:

Later, when I complemented Fou on her beautiful needlework, she said matter-of-factly, “Yes, my friends are proud of me because of my paj ntaub [The Hmong name commonly given to a form of embroidered textile art.] The Hmong are proud of me.” This is the only time I ever heard her say anything kind about herself. She was otherwise the most self-deprecating woman I had ever met. One night, when Nao Kao was out for the evening, she remarked, out of the blue “I am very stupid.” When I asked her why, she said, “Because I don’t know anything here. I don’t know your language. American is so hard, you can watch TV all day and you still don’t know it. I can’t dial the telephone because I can’t read the numbers. If I want to call a friend, my children will tell me and I will forget and the children will tell me again and I will forget again. My children go to the store to buy food because I don’t know what is in the packages. . . . too many sad things have happened to me and my brain is not good anymore.” (103)

Then, a bit later along, we are shown that this particular family’s status as refugees derives, in part, from the fact that they were forced migrants from Laos, following the recruitment of their people into aiding the U.S. during the Vietnam war:

In Laos, [the Hmong] had already proven their mettle as guerrillas during the Second World War, when they fought in the side of the Lao and the French during the Japanese occupation, and after the war, when, similarly allied, they resisted the Vietminh. The CIA thus conveniently inherited a counterinsurgent network of Hmong guerillas that the French had organized in northern Laos two decades earlier (127). . . . In the United States the conflict in Laos was called the “Quiet War”. . . But for the Hmong, the war was anything but quiet. More than 2,000,000 tons of bombs were dropped on Laos, mostly by American planes attacking communist troops in Hmong areas. There was an average of one bombing sortie every eight minutes for nine years. Between 1968 in 1972, the tonnage of bombs dropped on the Plain of Jars alone exceeded the tonnage dropped by American planes in both Europe and the Pacific during World War II. (131-2).

And then, finally, a scene towards the end of the book where the author, Anne Fadiman herself, is waiting in a restaurant in Merced to meet a Hmong community leader named Jonas Vangay. Jonas, we discover, is a multilingual, transnational intellectual and activist who has devoted his life to helping his community adapt to the U.S.:

The restaurant’s hostess, who wore a silver lamé top and a mini-skirt, asked me whom I was waiting for. “A Hmong man who has helped me with my work,” I said. The hostess looked surprised. “I just moved to Merced,” she said, “and I don’t know it nothing about the Hmongs. I just saw my first one today. My boyfriend said, That’s a Hmong. I said, How can you tell the difference? They just look like Chinamen to me. My boyfriend says they are the worst drivers in the world. When he sees one, he goes clear ‘cross town to stay away from them! I guess Hmongs don’t come to restaurants like this very often.” (They sure don’t, I thought. And by the way, you’re not fit to polish Jonas’s boots.) (248)

Now, perhaps all of this feels much like a novel. And we’re certainly accustomed, for instance, to seeing writers “step back” in time, or to use individuals to make broader generalizations. If we’re of a literary mind, as well, perhaps we’ll notice that Fadiman makes several references to the Joad family of John Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath (1939); perhaps we will think of the scenes I quoted earlier from Jacob Riis.

However, Fadiman is actually mixing discourses. For example, the first passage above asks us to read anthropologically: she’s using an ethnographer’s discourse that asks us to see the family as an instance of cultural practices. We see this family not only as individuals, but as representatives of a cultural group or subgroup. Let me reprint parts of the passage, with some highlighting of the anthropological discourse behind it:

. . . no Hmong woman of childbearing age would ever think of setting foot inside a cave . . .

Once a Hmong woman became pregnant, she could ensure the health of her child by paying close attention to her food cravings. . . .

When a Hmong woman felt the first pangs of labor, she would hurry home from the rice or opium fields, where she continued to work throughout her pregnancy. . . (4)

In short, the mother here serves to “illustrate” a supposedly typical or normative behavior of her ethnic group. Lia’s mother is surrounded by “shoulds” and “musts”—she is governed by norms of her society and upbringing.

But then look what happens in the second passage. Not only is the name of Lia’s mother finally revealed; she actually begins to speak against or about what Hmong culture expects of her (and that she may not fit). (For example, Fadiman writes “She was otherwise the most self-deprecating woman I had ever met,” a discourse that singles her out.) And that’s because Fadiman has shifted into a discourse reflects presumptions in discourses that we commonly associate with psychology rather than anthropology. As a result, Foua is now given “depth” and individuation—indeed, she is allowed “unburden” herself in our presence as a possible path to health or relief. In turn, that helps us notice that the anthropological “generalization” about her not only didn’t fit, it may even have prevented her from speaking as herself. And thus, in a subtle way, Fadiman introduces the complex idea that simple tolerance of knowledge of “Hmong culture” and customs might not actually accord Lia or her family what U.S. medical care says about itself: that it provides individual care.

But in the third passage, we also learn that Fou’s sorrow is not solely attributable to the illness of her daughter, nor to the stigma of supposed cultural ignorance. And that’s because, of course, the fourth passage shifts into recognizably Historical discourse. (For instance, we hear that “they fought in the side of the Lao and the French during the Japanese occupation,” and they are enumerated in terms of the tonnage of bombs falling upon them.) It’s not that History hasn’t been present before—indeed, as some theorists have put it, narrative is itself “the manifestation in discourse” of particular ideas about the structure of time.[8] But even so, we can see that Fadiman is talking about geopolitical strategy and military convenience; she shifts into statistical counts, breaking numbers of bombs down into different time intervals so as to measure their possible traumatic impact (and thus a source of distress for Fou’s own family). And then Fadiman resorts to another familiar Historian’s tool: large-scale contrast built around irony, so as to call up how the “lost” or secret history of the Hmong (which we are now reading) might be as dramatic as the epochal-making stages, European and Pacific, of national identity in the past. History isn’t any longer a backdrop here: rather, it carries weight, tonnage and time, into the “now” of the narrative we’ve been reading.

And then the fourth passage—which moves back to the present, and show us Fadiman herself coming into her own book as the more personally involved investigator, the one who has accumulated views based on the intimacy with her subjects we’ve seen developing in the book. The discourse here is closer, now, to that of memoir—less, perhaps a “systemic” discourse than one that draws upon personal experience and emotion, recreating the actions of the creator of the narrator we’ve been following—and one here who “takes a view” in a particularly strong way: expressing anger, and perhaps even some frustration at the very inversions of “cosmopolitan-ness” and “primitiveness” around Hmong identity that her own investigative journey has taken her on.

Takeaways

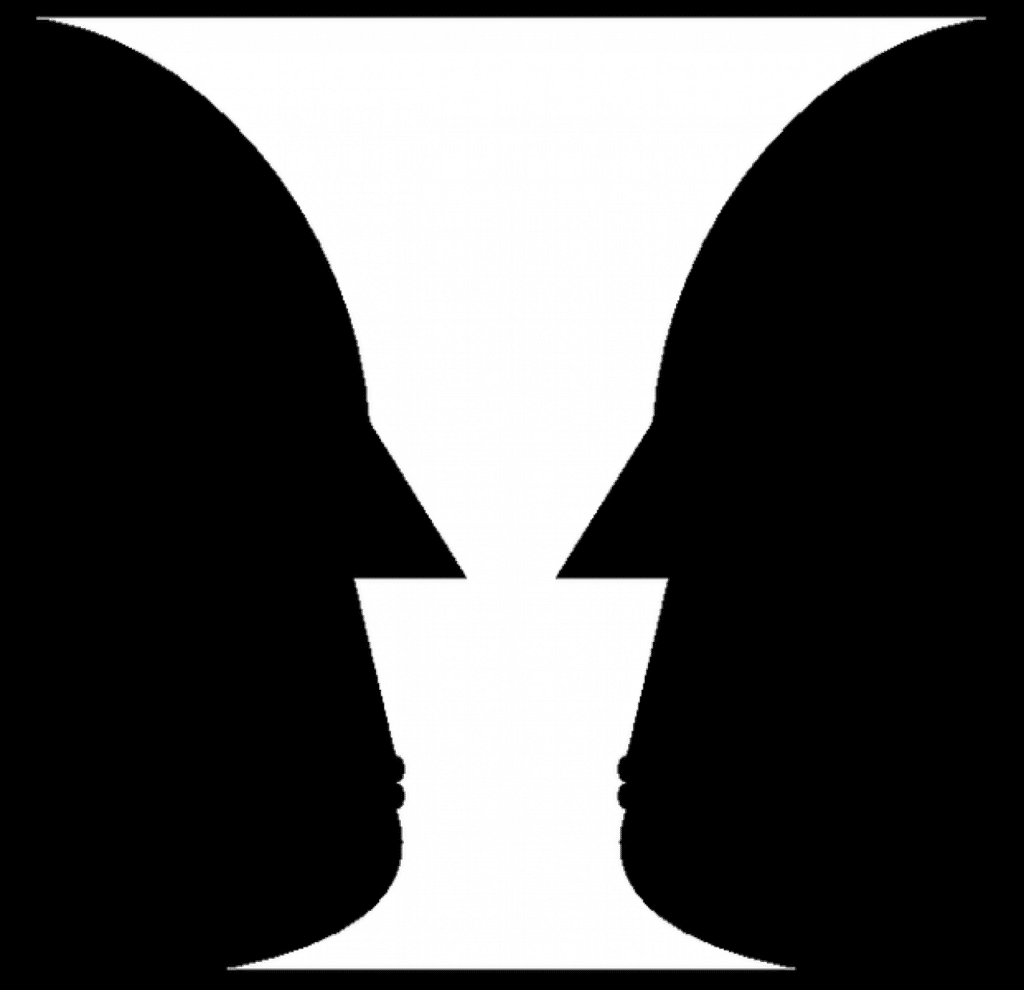

Fadiman is unique in how self-consciously she deploys these different discursive modes, and in seeing ways in which each one is partial or incomplete. Indeed, at one point, she expresses her view, illustrated by the visual aid I’ve put here, that “[s]ometimes [she] felt that the Hmong of Merced were like one of those visual perception puzzles: if you looked at it one way you saw a vase, if you looked at it another way you saw two faces, and whichever pattern you saw, it was almost impossible, at least at first glance, to see the other”(237). But this comparison itself also suggests how Fadiman allows one discourse to revise the other, complement it in the sense of filling in what the rival or previous discourse left out. Each piece of the perceptual puzzle complements but is not in itself complete. What we’re assembling is more like a mosaic than a completely cohesive portrait: these conventions, modes and discourses often fit together only roughly, and sometimes their interpretive drives actually compete with each other for meaning. At times, as well, we see the gaps between them. That is, instead of seeming like a “seamless” story–an effect of realism I referred to in Chapter 3—it’s as if your text starts showing all of it seams. Or, you might say that it starts to look more like a quilt, a scrapbook, or even an abstract collage.

There are other books that perform this mixing of modes. Isabel Wilkerson’s Warmth of Other Suns (2010), for example, shifts from an “epic” mode to historical debates and to personal reminiscences about the experiences of her own mother. Emma Larkin’s brilliant Finding Orwell in Burma (2005) blends biography, travel writing, colonial history, and even a bit of literary criticism. What this tells us is that sometimes the authority of a work of reportage is not only contingent on direct witnessing, but on feeding off the interpretive frameworks of other discourses, such as those from literature or social sciences or History. From ways of seeing and explaining that are already authoritative in our eyes. And as a reader, sometimes your job is to compare one or more element to another: to let the conventions, modes, and discourses speak to each other.

In my final chapter, I mean to look at what happens when journalists push things even further–into more experimental, and sometimes even postmodern modes–that again help us to rethink the basis of journalistic authority itself.

A Study Sheet on Genres and Modes

Common Literary and Journalistic Modes

Notes

- All page citations from Riis’s How the Other Half Lives come from the Google books edition. Ben Yagoda, About Town: The New Yorker and the World It Made (New York: Scribner, 200), 133 ff. I have discussed this phase of Riis’s study in “”Markets and Players: Plotting Poverty and Citizenship in Matthew Desmond’s Evicted,” Journal of American Studies , Volume 56 , Issue 1 , February 2022 , pp. 167 – 190. ↩︎

- Roy Peter Clark, “The False Dichotomy and Narrative Journalism,” Nieman Reports 15 Sept. 2000. ↩︎

- For one such critique of Sheehan see, for instance, Richard Rodriquez’s review of Life for Me Ain’t Been No Crystal Stair, in the Washington Post, 10 October 1993. ↩︎

- See, for instance, Ehrenreich’s disavowal that she is writing “undercover” journalism, in the Introduction to Nickel and Dimed, p. 6. ↩︎

- Mary Louise Pratt, Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation (London: Routledge, 1992). ↩︎

- I have drawn here on Augustin Zarsosa, “Melodrama and the Modes of the World.” Discourse 32 (Spring 2010): 326-255. ↩︎

- There has been a good deal of recent commentary on the religious dimensions of Riis’s photography and lectures; see, for instance, Gregory S. Jackson, “Cultivating Spiritual Sight: Jacob Riis’s Virtual-Tour Narrative and the Visual Modernization of Protestant Homiletics,” Representations (Summer 2003): 126-166. ↩︎