Welcome to Reading Narrative Journalism

And welcome to some of the most exciting and challenging readings of our time. The five Chapters of this site are designed as a multimedia textbook of sorts, aiming to help you explore critical methods for reading what is commonly called narrative journalism–specifically, journalistic narrative printed in the U.S. over the last century and a half.

These days, it is often said we are living in a “Golden Age” of this style of writing. And though this site focuses exclusively on U.S. authors, narrative journalism is an international phenomenon as well (see, for instance, the International Association of Literary Journalism Studies). Meanwhile, the “tribe” of narrative journalists is a diverse one, and their writing takes many forms: profiles of famous thinkers or celebrities; exposés of corruption, poverty, homelessness; “long-form” articles and books about international migration, prison experience, gender politics; and much more. We often read these works because we love being caught up in dramatic stories that dive deep into the thing we call “the news.”

And so, perhaps you’ve started taking a course about this kind of writing, or maybe you’re an aspiring journalist yourself, and you want to know the tricks of the trade. Maybe you’re a teacher or scholar looking for classroom exercises. Whatever your interests, this site has many offerings:

- Discussions of some of the most famous writers in this tradition: Joan Didion, Michael Herr, Anne Fadiman, John Hersey, Barbara Ehrenreich and many others;

- Discussion of the standard and experimental stylistic effects those writers use;

- A Glossary of terms and a bibliography of scholarship in the field;

- Discussions of critical issues in the field about “objectivity,” “realism,” and other controversies;

- Study sheets and classroom exercises; and more.

As you can tell, then, this isn’t a standard textbook that teaches you how to be a reporter, or a “style handbook” for polishing your prose. Rather, it’s a site that teaches what’s at stake in reading these exciting texts–and offers an introduction to critical issues around doing so.

The Goals of This Site

That is, much as you might be taught how to analyze a poem, a legal case, or a political speech, this site offers some practical tips on taking apart and arriving at a deeper understanding of journalistic story-telling. Or, as I’ll be saying, it’s about how to become an active, critically-minded reader of narrative journalism. I hope to give you new ways to get into the spirit of what you read, understand more fully what makes this brand of writing so engaging, and discover ways to argue against it, or see some of the limitations of any particular story or article. And, in turn, explore some issues and controversies that have arisen alongside these powerful writings.

Now, I’ll admit, it might seem a little contradictory to be told that you need to learn how to read journalism. Isn’t reading journalism, you might ask, the most straightforward kind of reading one can do?–isn’t it just a matter “taking in” the story that the journalist tells you?

That’s a natural first reaction. We tend to approach works of nonfiction as if they are just providing facts, and our first instinct is to think that there couldn’t be anything very complicated about that. We read journalism simply for the picture of the world it’s presenting, much as if the text is just a window through which we look at the world.

And sure, there are lots of ways you can react to a journalistic article or a book. Maybe you didn’t like a character’s personality, found the voice of the work too cold or distant, or thought there was too much detail or not enough background information. Everyone has different tastes. Or maybe you disagreed with what you thought the journalist was implicitly arguing. But simply reacting or disagreeing isn’t our goal here: instead, our goal is analysis. What we’re after is learning how to be more like a mechanic working on a car engine: you take it apart and then put it back together so that you understand how its parts work together to produce both compelling storytelling and an interpretation of the world(s) it presents.

Really, the first place to start is to embrace the constructed nature of the work of narrative journalism you’re reading. And that means being on the lookout for what I’ll call the “Dimensions” of Narrative Journalism that go into that construction.

What do I mean by that? Well, as you start out, I think it often helps to think of a work of narrative journalism as a little like a “lens” through which we look at the world it presents—a lens like you find on a telescope or a microscope. A lens has edges or (with glasses) a “frame” around it, and of course; sometimes we can see outside those edges. But mainly a lens asks us first to see through it—to see the “world” (and the parts of that world) it selects and recreates for us, brings into better focus. A lens, then, isn’t simply “distorting.” On the contrary: like a pair of glasses, a journalistic lens usually tries to correct or improve our vision, maybe because we have distorted or blurry visions of the world to begin with. A lens can also allow us to zoom in on something more closely, see it better than we otherwise might.

Inevitably, though, the lens also necessarily causes some things to be less in focus, perhaps things that are in the foreground or in the background or outside the lens altogether. And that’s how you can begin to critique a work of narrative journalism, as well. When I say a work of narrative journalism is a constructed “interpretation,” this is what I will mean: that it shapes our understanding of its topic (poverty or war or immigration, and so on). A work of narrative journalism is not, therefore, a window or a mirror: instead, it causes our line of sight to be reshaped so that we see in a particular way. And like any lens, many things go into its construction–many dimensions are built into it.

So, what Are those Dimensions?

Here are 4 that are foundational to the work of the Chapters ahead:

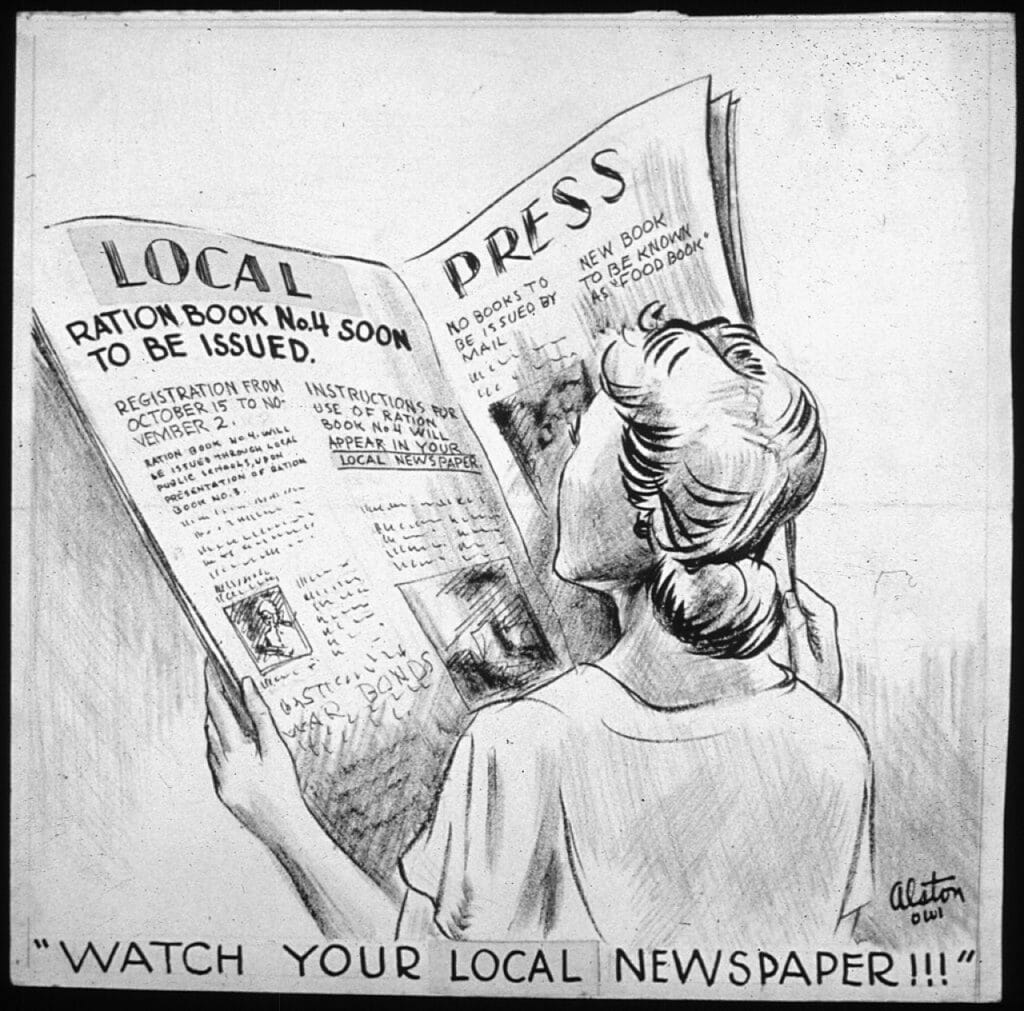

Dimension #1. Legwork. You’re probably familiar with this term: it’s the word journalists generally use for the research they put into their story. Long-form journalism usually has loads of research behind it. But for this site, I also want you to think of legwork in a more specific sense: as a word more like “the journalist’s footsteps,” the record of the path that the journalist went on while making their account. Re-trace where the journalist went, who they talked to, the patterns you can see in their itinerary. Where was information to be found in their news story, and how did the journalist get there?

Dimension #2. Narrative. We often start out thinking this is a fancy way of just saying “story”–or sometimes the “plot” of what we’re reading. And it’s true: we love a good story; as John Hartsock has written, we often remember events better if they are put into the form of a story rather than having them just explained or described to us. (Hartsock 19). But to begin with this site, try out this fuller idea: that a narrative is a set of events, selected and arranged in a particular order, recounted from a particular point of view. Notice that there are components to this definition:

- what events are selected for us to examine,

- how they are put into a sequence or order (which is first; which is dealt in depth; how time is organized)–and

- how they are told from a particular vantage point (one person or more; a point in time; with what knowledge in hand).

A good synonym for this sense of narrative is “story-form.” That is, journalists will give their stories a structure or design, a “shape.” For instance, maybe a story about the war in Iraq will follow a battalion of soldiers through five specific characters. Or perhaps it will adopt a different structure, change the “vantage point” from which we see things–for instance, splitting the story-telling between a commanding officer, then a foot soldier, then a medic. It’s also helpful to think of what you read as constructed like the acts of a play: you break down a long-form narrative into parts, and decide what is the first act, the second, the “reveal” and so forth. Sometimes that means a “dramatic climax” will appear, as in the diagram below:

Dimension #3. News content. Obviously, we read works of long-form journalism to get a deeper sense about pressing social issues or conditions–about poverty, about what it’s like to be a prison guard, or a soldier in war. But by news content, we mean more than this: it’s a phrase for how particular issues about a subject have come to matter to us, as readers. Or, in some cases, a journalist’s case for why they should matter: why they have value, “worth,” in ways we perhaps haven’t considered. For example: that people are “poor” isn’t news: specific things about the poor are. And so, for instance, a writer may focus on children’s exposure to violence as an effect of poverty; how they experience foster care–and so on.

Dimension #4. And finally, pay attention to the subjects within a work of journalism. You might think by “subject” we mean the “topic” of a given work. But in this site I’m using the word more like scientists or social scientists use it: as a word for the persons who are depicted in the story. That is, in any work of journalism, the reporter has usually come to rely upon—or, in some instances, modify or contradict—the story told by the actors or players in the tale that is being told. Subjects can play many roles. Perhaps these people are sources for the story; perhaps they are characters at the center of what we’re reading; perhaps they’re on the edges of the action, and we barely notice them. What I’m going to be suggesting, though, is that one of the best ways to achieve an active, critical reading is to tease out how those subjects might themselves tell their story, and compare it to the one you’re actually reading.

(As you may know, there are lots of professional and ethical issues, these days, about how journalists form relationships with their subjects; when and where the story a journalist tells departs from the subject’s, and when it doesn’t; and whether the subject of a news narrative is given enough “voice” of their own.)

Often, analyzing a work of narrative journalism means playing off one of those “dimensions” against another–and, as I’ll be saying, seeing if you can keep all four in mind. For instance, you might ask: how did the pattern in the legwork reflect what a journalist thought was important–and thereby shape the narrative? Or, did the journalist simply re-tell the subject’s story–or did the journalist choose distance, depart from that story? Or how did the shape of the narrative–which characters were chosen, how many, whether we got into their point of view–affect what we were able to see about the subjects’ lives?

The 5 Main Chapters of This Site

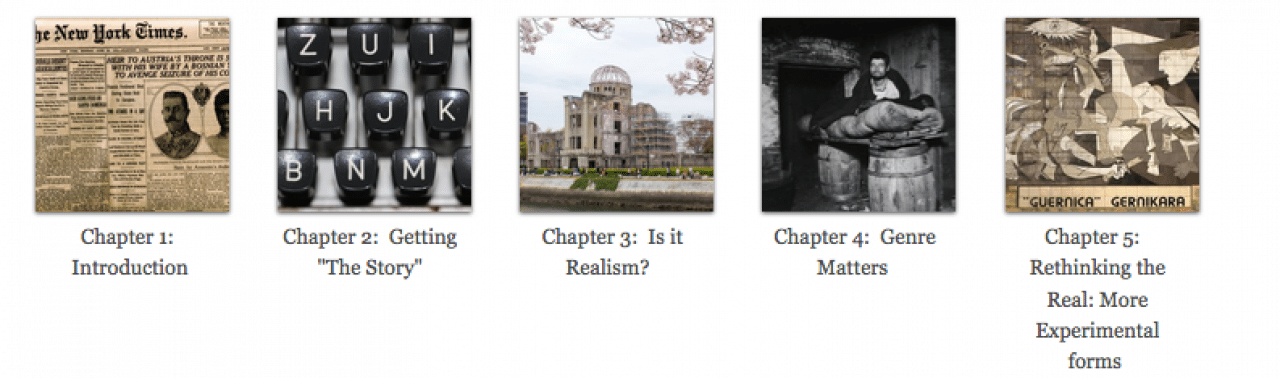

As you can see on the “Table of Contents” page, there are five chapters that provide the main narrative line of this site:

- Chapter 1, which you’re reading now, gives an overview of this site and lays out some “first principles” for the chapters that follow;

- Chapter 2, which discusses the different meanings that journalists attach to the idea of “the story”–and how to start reading for those “four dimensions” ;

- Chapter 3, which discusses why so many journalistic stories seem “realistic,” and the many ways they create that literary effect;

- Chapter 4, which talks about how narrative journalists use different literary genres and conventions, thus shaping the social and political interpretations they offer; and

- Chapter 5, which discusses some of the more famous of “experimental” and “New Journalistic” techniques writers have used over the years.

- There is also a brief “Afterword” at the end of these Chapters, looking back on the project as a whole.

And so, to summarize. . .

I also think you can get a good sense of my goals here by considering a question that originally came from one of my own students–who asked the following: “When we read a work of narrative journalism, what should we be looking for, paying attention to, and thinking critically about? That’s what I’m going to be trying to do in this site: to show you what it helps to be looking for.

And again, the central premise behind Reading Narrative Journalism is that works of narrative journalism are especially unique and challenging precisely because, unlike many other kinds of texts we encounter, arriving at a critical reading typically involves thinking about more than one of the four crucial dimensions I’ve outlined at a time. Or, as I’ll be saying, “Reading in 4-D.”

So: feel free to get started!

But….maybe before you do…

You might want to browse through a set of responses to Frequently Asked Questions that you might still have. These are listed below, at the end of this Introduction:–for example, “Is there a Shorthand Definition Narrative Journalism? or “Is there a Set of Rules for Writing Narrative Journalism”?–or How are Those Rules Enforced?” (See these FAQ’s listed in the menu to your right).

Likewise, you’re encouraged to look around the Table of Contents a bit and “dip into” a few reflections I”ve grouped together under different headings. For instance, you might look at the grouping I’ve called “Short Takes.” There are shorter entries there, for instance, on concepts like “objectivity,” a few glossary terms you can glance at before starting, tips on paper writing and more. You might think of these as “warm up” exercises, or places to turn if you have questions still unanswered.

Finally, in the table of contents you can also find a “Glossary ” that will include some of the more technical terms I will be using along the way. Those terms will also be flagged by underline words in each chapter. As one example, if you’re still unclear about what I mean about “the subject” above, you could look at the glossary item on “reading for the subject”.

Here are the FAQ’s:

=============================================

FAQ #1: How is narrative journalism defined?

As you may already know, the body of writing covered by this site goes by various names: “literary journalism,” “narrative journalism,” or “long-form journalism,” to name just a few. Again, what these terms all refer to is journalistic writing that puts matters of pressing public interest into the form of a story–for example, with “characters,” a plot line, and so on–and tells that story from a particular point of view. (Here, you can also look at the Glossary entry on “narrative.” ) For example, narrative journalism would include

- accounts of poverty in the United States like Jacob Riis’s How the Other Half Lives (1889), Alex Kotlowitz’s There Are No Children Here (1992), or Adrienne Nicole LeBlanc’s Random Family (2003);

- John Hersey’s classic Hiroshima (1946), a book about the days immediately following the dropping of the atom bomb on Japan;

- accounts of migration, like Isabel Wilkerson’s masterful story, The Warmth of Other Suns (2010), or Sonia Nazario Enrique’s Journey (2006);

- or works like Michael Herr’s Dispatches (1977), David Finkel’s The Good Soldiers (2004), or Helen Thorpe’s Soldier Girls (2014), which convey the experiences of men and women in and after wartime.

Of course, that list might include other nonfiction works on important subjects like postcolonial conflict, transnationalism and globalization, the prison boom, contemporary sports, the drug wars, and more–by writers such as Joan Didion, Anne Fadiman, Michael Lewis, Katherine Boo, Michael Massing, Cristina Rathbone and many others.

FAQ #2: Does It Go by other names?

Well, for starters, you can see that I’ve already been using different labels for the kinds of texts that I’ll be discussing on this site. Most often I will use three different terms: along with “narrative journalism,” I will call them works of “reportage,” or “long-form journalism” as well. Of late, some have also taken to calling such texts forms of “slow journalism,” to refer to the extensive immersion, intensive research, gradual editorial development and aesthetic care that they commonly entail. (If everyday news is “fast food” narrative journalism is not.)

Now, to specialists, even these three labels signal not only subtle descriptive differences, but different institutional and national histories as well. For example, “reportage” is commonly assumed to derive from French, where it usually refers to a long tradition of documentary-style reporting. Many scholars would prefer that we use “reportage” to refer to investigative reporting or exposé. Likewise, in the U.S., the label “long-form” often refers to news features and magazine pieces, not only to books. For example, Leon Dash’s portrait of the impoverished, drug-dependent Rosa Lee (1996), which runs some 279 pages, or Sherri Fink’s 576-page Five Days at Memorial (2013), about Hurricane Katrina and a New Orleans hospital, both began as newspaper features. Other writers prefer to use the term “literary” journalism, because they’re interested in literary status or closer connections to traditions in fiction and memoir. Many of these scholars that tend to see today’s narrative journalism as an off-shoot of the “New Journalism”—that is, experimental forms of narrative journalism associated with writers such as Tom Wolfe, Truman Capote, Joan Didion, Michael Herr, or Norman Mailer—forms like those I will discuss in more depth in Chapter 5.

A great deal of useful critical thinking, history, and literary interpretation has been raised by scholars investigating these terms, too. (And I have samples of them in the resources sections of this site.)

There are some good reasons, though, not to get too hung up on labels when you’re starting out. Any time you establish one definition, or start setting up a “norm” for a particular group of texts–well, before long, you start excluding other kinds of work you should be thinking about (and reading). And as I will explain further in Chapter 4, there are problems in thinking of narrative journalism as a single genre unto itself–or as one “thing” we might define or classify. There’s just too much variety of style and investigative technique.

FAQ#3: Is there a set of “Rules” for Narrative Journalism?

What rules do narrative journalists work by?–and how are these rules enforced? There’s been a lot of ink spilled on this question. Here are some rough guidelines:

First, by calling a written text a work of journalism, we’re assuming that it is a “factual” or nonfictional account, and it is aimed at exploring issues of common or public interest. Specifically, we assume that its content is “verifiable,” in the sense that we assume that someone else, given the notes or supporting documents, reproduce the same information as the the long form reporter we’re reading did. (For example, suppose another journalist or editor went back to re-check the quotes from a given long-form journalist’s interview. In theory, either a tape, or reporter’s notes, or the person interviewed would confirm what was quoted or, to use the key work journalists use, attributed.)1 .

Some writers have worked out corollaries from that basic rule that attempt to see narrative journalism in what you might call “trade-friendly” terms:

- For example, as one writer (Mark Kramer) has put it, many assume that it should be a given that the long-form journalist will “[create] no composite scenes, no misstated chronology, no falsification of the discernible drift or proportion of events, no invention of quotes, no attribution of thoughts to sources unless the sources have said they’ve had those thoughts.”

- John McPhee of The New Yorker, likewise, has written that ‘[y]ou don’t make up dialogue. You don’t make a composite character. . . . And you don’t get inside their [characters’] heads and think for them.”2

- or, you can look at a few other narrative journalists’ video lectures and essays I’ve collected, too, in the video Interviews and lectures on this site.)

This preliminary list of rules would indeed define the governing standards for the vast majority of narrative journalists, particularly those who write for established magazines or newspapers. or respected book publishers. That’s why I suggest they might be seen as “trade friendly.” But keep reading…

FAQ #4: How are those rules enforced?

Newspapers and magazines and well-regarded nonfiction book publishers do employ fact-checkers, and require note-taking or documentation by their reporters. They also often insist upon double-checks that, for example, require that, if a journalist says something unflattering about someone in a news story, that person should be allowed to comment on it before going to press. And so on. There are strict institutional no-nos, in particular, about what is typically called any kind of invention (in short, making anything up). Thus, the “poetic license” commonly granted autobiography, or sometimes “creative nonfiction” (CNF; see below), are not only typically frowned upon, in the trade or in journalism schools–they are commonly regarded as taboo. That is, when it is discovered that a narrative journalist didn’t stick to the facts, they will only fall farther down the hierarchy of the newsroom, and in worst-case scenarios they will be fired and/or drummed out of the profession. Even if you’re not an aspiring journalist, sooner or later you’ll hear about the misadventures of Jayson Blair, or Stephen Glass, or Michael Finkel–let alone the made-up stories by freelancing authors like Greg Mortenson, James Frey and others.3

Long before the recent controversies over social media and “fake news,” it was obvious that there were reporters who could indeed end up either abusing the trust their employers (and us) have put in them, or capitalizing on the reading public’s thirst for sensation by exaggerating or inventing “fact”-based stories. Even well-intentioned long-form reporters can fall into errors of fact created by relying too much on their sources, on unreliable informants, or on manipulative public figures; news offices can be bureaucracies like any other, and sometimes the buck gets passed and stories go to print that never should have. And retractions are costly and embarrassing. If you’ve spent any time in a journalism course, you probably have been told that the rules I’ve outlined are ironclad, and that would appear to be that. No exceptions.4

However, in practice, it’s really not ever quite that straightforward. For one thing, even the most vocal defenders of these golden rules are sometimes forced to admit that, given the complicated system of news production behind these texts, these standards of verification are not always so easily enforced. Breakdowns in the newsgathering and fact-checking system happen pretty frequently, and many notorious scandals have appeared (and not just in the U.S.) over the past fifty years or so. Fact-checkers or vigilant editors can’t catch everything, and there’s more wiggle room in news production to begin with. In fact, some think that journalism as a system has actually been designed to provide a measure of personal autonomy for reporters. A good deal of the ethical rules behind what reporters actually do are what we might call “self-regulating” rules: reporters don’t always have someone looking over their shoulder all the time. Rather, the system largely works by assuming that reporters–espeically long-form reporters do their work by having internalized the professional-ethical rules that they carry out into the world with them. Thus, when a reporter says they witnessed something, readers usually take for granted that they really did, even when we might have to admit that there was little way a newsroom (or anyone else) could actually have verified the story itself. In short, it can involve a leap of faith.

Ethical lapses can also happen, however, because not all journalists have internalized these “in-house” norms of the profession. Freelancers are commonplace in the trade, and sometimes they aren’t subject to the same oversight, or have the same rigorous training, as staff writers have had. Meanwhile, a good many journalists don’t see themselves as bound by the same strict rules as other professions at all (or, let it be said, the same rules as academic investigators who must answer to Internal Review Boards [IRB’s] regarding the ethics of their work.)5 Instead, they will say, creating a work of narrative nonfiction can involve very tricky negotiations, often involving adversarial relationships with sources and subjects, occasional rule-bending. Sometimes, for example, a long-form reporter will disguise a source’s name or location to protect that source’s confidentiality. And in fact, instances of provable invention in works claiming to be “journalistic” represent only a tiny fraction of the trade. (The sensational lapses just get more ink.)

So, what do you do as a reader?

Well, I think it’s best to keep a level head, and balance a healthy respect for the norms of journalistic practice with an alertness to when these norms might not always be working to perfection. And be aware that a mistake of one kind or another–and even a moment when a journalist “disguises” their sources–doesn’t cancel out the legitimacy of the entire work. As notorious as some scandals have indeed been, they can also be something of a distraction when it comes to absorbing the primary business of Reading Narrative Journalism–which, again, is learning to read the interpretation of the journalist critically in the first place.

In other words, active, critical reading is often the best check against abuses of the rules–and it’s something you do as a reader. That’s why I’m emphasizing it on this site.

FAQ #5: Is “Creative Nonfiction” journalism?

However, as you may already know, there is another school of thought out there that often challenges the very notion of narrative journalism itself. Some will say that the kind of writing examined in this site should more accurately be grouped within the broader category of “creative nonfiction” (CNF) rather than distinguished from it. In other words, these thinkers view narrative journalism simply as a subset or wing of CNF. (Or, perhaps a more traditional form of CNF.) The only real difference between the two kinds of writing, some of this school of thought will say, is that writers of creative nonfiction are more candid or self-conscious about the fact that any move in the direction of “making a narrative” it is, by definition, engaging the arts of imaginative reconstruction and even, yes, invention.

Journalists, these folks will point out, are subject to the same kind of fallibility of memory, the temptations to impose their thoughts and feelings on their subjects, and so on; the more meaningful way to think about what we should call CNF, these critics will say, is to regard it as a “border-crossing” or “genre bending” form that blends (or, if you like, creates a “hybrid” or “mash up” of) journalism and fiction. Some of these critics will even extend this argument further, and say that invention invariably creeps into the form, despite those “rules” I quoted earlier from writers such as John McPhee or Mark Kramer. CNF advocates often point to the fact that writers like Truman Capote and Michael Herr (or, on the international front, Ryszard Kapuscinski or George Orwell) are now acknowledged to have invented characters or scenes in their books.6 Not uncommonly, in fact, this controversy quickly becomes part of what the so-called “fact-fiction” debates around journalistic invention. As you may be sensing, such debates7 can be quite divisive, even polarizing. If journalists can be close-minded about CNF and about “postmodern” writing generally, sometimes CNF writers and scholars can be dismissive about “old-fashioned” claims to journalistic authority.

So, how can we sort this out?

My own “take” is that the polarization of these debates is usually unnecessary. Reading Narrative Journalism, in fact, is meant to show you how each side in this debate has something to offer you. My hope, in fact, is that if you move through the chapters of this site, you’ll see why. That is, in Chapters 2 and 3, starting with the professional “rules,” I try to explain why what I call “empiricist ” norms and values have persisted in American journalism, and why (in turn) so many writers prefer “realistic” forms of story-telling. But gradually, and especially in Chapters 4 and 5, I try to shift course a bit, to introduce some of the insights of CNF scholarship (and academic criticism more generally), to show how they can aid our understanding of narrative journalism, too. Chapter 5, in particularly, takes up what is roughly called postmodern experimentation, the very thing that some of journalism’s defenders seem to be so nervous about. The idea that literary technique (even postmodern techniques) intrinsically constitute a threat to the journalistic character, much less the authority, of a given work of reportage–well, that complaint needs re-thinking.8 On the other hand, CNF scholars and writers are also often too quick to dismiss the public investment in journalism–indeed, the fact that we are all, as the sociologist C. Wright Mills once put it, deeply dependent on the “second-hand worlds” that journalists (among others) create for us.9

And that’s one of the main goals of the site you are reading: to strike a balance. And that’s also why we have to think hard about our own role as readers when we come to reading narrative journalism. Why do we read it?–for what purposes? And in turn, if you’re starting out, what do I think you should be reading “for”?

In the next Chapter, as I’ve said, I’ll expand upon the four different ways we can approach “the story” in a work of long-form or narrative journalism. And how, in turn, we can begin to unlock the balancing act behind it. Thanks.

Notes

- Note that here I am saying the “quote” or the attribution, not the same “story.” On this kind of variability, I often send students to Robert Karl Manoff, “Telling the News By Writing The Story,” in Manoff and Michael Schudson, eds. Reading the News : A Pantheon Guide to Popular Culture (New York: Pantheon, 1986). ↩︎

- This is list from Mark Kramer, as quoted in Norman Sims and Mark Kramer, Literary Journalism: A New Collection of the Best American Nonfiction (New York: Ballantine Books, 1995): 25. McPhee as quoted in Bill Kovach and Tom Rosensteil, The Elements of Journalism (New York, Crown Publishers, 2001), p. 78. I have relied on Kovach and Rosensteil, as well, for their idea that “objectivity” is a method; see also Gaye Tuchman, “Objectivity as Strategic Ritual: An Examination of Newsmen’s Notions of Objectivity,” Journal of American Sociology 77, no. 4 (1972): 660–79. For a helpful overview of more recent scholarship on this often-misused and misunderstood concept, see Mark W. Brewin, “A Short History of the History of Objectivity,” The Communication Review 16, no. 4 (2013): 211–29. ↩︎

- Jayson Blair invented stories and sources for The New York Times ; Stephen Glass for The New Republic. Greg Mortenson, author of Three Cups of Tea (2006), and James Frey, author of A Million Little Pieces (2003), were challenged around independent memoirs they had written. ↩︎

- For a good introduction to these in-house practices, and where they can go wrong, see the Columbia Journalism School report on the Rolling Stone story alleging gang rape at a fraternity at the University of Virginia, at Rolling Stone’s investigation: ‘A failure that was avoidable’ – Columbia Journalism Review ↩︎

- Journalists are often said to be legally exempted from so-called “IRB’s,” out of First Amendment considerations. See the article in the “Authors and Editors on Method” section of this site, by Charles Seife, on this matter. ↩︎

- One fine discussion of this kind of dispute is Ben Yagoda’s review “Fact Checking ‘In Cold Blood,’” in Slate 20 March 2013, and hopefully still available online at Fact Checking “In Cold Blood.” ↩︎

- While is true that some rapprochement has been ongoing, for example in graduate creative writing and English programs, many professional journalists and editors remain distrustful of the label “CNF” itself, even if writing programs are not.. ↩︎

- On the other hand, I can also find myself feeling that some of the arguments against journalism coming from CNF advocates can be a little wobbly, too, at times. Perhaps the biggest flaw in the case made by CNF’s most extreme devotees (at least in the U.S.) is that they underplay the public investment in the canons and rituals of verifiability. (Even when the public distrusts the “media” generally, as it does now, it often remains invested in its ideals.) Just ask anyone about how they feel about being misrepresented, themselves. I would myself insist that we can and always should contest the interpretations these acts of reporting have given us. But we need to do so without falling into the easy out that “all reporting is subjective” when, in fact, this misconstrues what the clearest notions of journalistic views of objectivity are. These conflicts are evident in John D’Agata and Jim Fingal, The Lifespan of a Fact (2012). ↩︎

- C. Wright Mills, “The Man in the Middle,” The Politics of Truth: Selected Writings of C. Wright Mills. ↩︎