Guiding Questions for This Chapter

What are some of the more “experimental” story-forms and styles that narrative journalists have used?–and what do we mean by the term in the first place? How do we respond to narrative journalists who intentionally include not just their personal reactions to a news story, but their emotional states as well? And how can we best address writings that move beyond realist conventions, or try out techniques that are modernist, postmodern, even what we might call “surrealist”?

I’d like to start this final chapter by reflecting back one of many insights that I’ve learned from my students. It happened during a discussion of Michael Herr’s Dispatches (1977), probably the most famous American war correspondent-memoir of the Vietnam War. At the time, I was presenting the class with some difficult problems regarding Herr’s documentation.

Now, in general, Herr’s memoir is so personal that perhaps we’re already liable to be a little, well, suspicious of some of these tales. After all, Herr has been telling us about having taken psychogenic drugs during some of his combat runs, and he also recalls a vivid, horrific battle scene that turns out to actually be a nightmare he would have, back in New York City, years later (69). (Herr often says that he can’t always tell the difference–and often, neither can we.)

But no, in that class we were discussing an apparent problem of sourcing that comes with stories Herr “collects” from soldiers and other correspondents. Really, stories from two two kinds of sources:

- stories that are either presented as originally told to Herr himself,

- or stories he has heard from others–usually from a single source: a soldier he has met, or a correspondent Herr has known.

Here are some sample openings from these kinds of stories:

A senior NCO in the Special Forces was telling the story: “We was back at Bragg, in the NCO Club, and this school-teacher comes in an’ she’s real good lookin’. . . . (169)

A twenty-four-year-old Special Forces captain was telling me about it. “ I went out and killed one VC [Viet Cong] and liberated a prisoner. Next day the major called me in and told me that I’d killed fourteen VC and liberated six prisoners. You want to see the medal?” (172)

Bob Stokes of Newsweek told me this: In the big Marine hospital in Danang they have what is called the “White Lie Ward,” where they bring some of the worst cases, the ones who can be saved but who will never be the same again . . . ” (174)

As striking as these stories are, Herr seems not to have offered visible corroboration for so many of them. For one thing, some of Herr’s sources are either anonymous or left unidentified. Meanwhile, the style of the stories can seem passed along, as if they were not witnessed but rather overheard or received, like rumors or exaggerations. If the first example above sounds like the start of a joke (“A guy walks into a bar,…”), the others come across as more like re-told stories that have gathered force or simplicity in memory, precisely because they’ve been made more striking by different people re-telling them over time. (That’s doubtless one of the many meanings, as I’ll say below, of “rounds” in one of Herr’s chapter titles, “Illumination Rounds”—these tales may be like “rounds” in the musical sense, a chorus sung over and again.) But as this seemingly shaky pattern of sourcing starts to pile up, our response to Dispatches as a whole may well start to change. In fact, we might even wonder if we’re reading journalism at all.

And so, here’s the question I put to my class: “What do we make of such apparently ‘loose’ sourcing?”–and my students immediately got what I was driving at. What if some of these stories may not just feel like legends—what if they are legends in the sense that they are not stories we can be sure actually happened at all?

And that’s when particularly sharp student raised her hand, and said the following (I’m paraphrasing): from her standpoint, such distinctions about sourcing didn’t really matter, because the thrust of Dispatches was primarily, she said, “phenomenological.” Or, in other words, Herr’s primary intent was to present the experience of Vietnam as it had been perceived, or felt, even if that meant that some things that seemed factual were not precisely or couldn’t be shown to be so. And indeed, if that student was right, her premise suddenly changed the rules of what we were reading almost completely. Because now, things that are told to Herr with single sources, or overheard or passed along or indeed originally fables, and yes even outrageous claims and even drug-induced hallucinations–well, practically all of it could now be justified as conveying how the war felt to Herr, was perceived by him—and indeed, how it may have felt to many of his subjects as well. That, after all, my student pointed out, Herr’s intent was not simply to tell us what Vietnam had been like, but to re-create something like a virtual-reality sensorium for the act of reading itself. Maybe these “legends” got closer to his true experience of the Vietnam war than more mundane facts he might have gathered about it.

Now, it’s important to be clear here. It’s not that this explanation would satisfy everyone. Not all readers, for instance, would pick up such a distinction as they read. We might also legitimately ask: “how it felt to whom?” For instance, if we apply our “4-D” criteria to vetting the book’s interpretive thrust, we might come to feel that Herr’s representation of the Vietnam war is hardly reflective of the experience of the Vietnamese themselves. In fact, Herr often presents the Vietnamese in Orientalist, and some would say racist terms. (Asians as inscrutable or uncanny, and so on.) That Herr would later be on record saying that a couple of the most central characters in his book were actually invented doesn’t help, either (though sometimes I think it is Herr’s “confession” that is really the invention).1

My main hope in this final Chapter, however, is that you can leave Reading Narrative Journalism thinking about varieties of stylistic experimentation in a different way. I will proceed in three phases. Starting out, I’m going to explain why certain journalists do modify or abandon the mainstream or “realist” norms that I’ve described in Chapters 2 and 3. Second, I’m going to look at forms of testimonial journalism, circling back to Herr’s approach in Dispatches. And thirdly, I’m going to take an extended look at a quite controversial, indeed experimental work of narrative journalism: Joan Didion’s Salvador (1983), a book that offers not only an account of a civil war in Latin America, but a harsh critique of how the American media represented that conflict. In fact, all through this Chapter, I’m going to suggest that many works of experimental journalism can, like Salvador, be read as “meta-journalism”–that is, as a journalistic work that is partly about reporting and its pitfalls and perils.

I hope you won’t pass over that last point too quickly. And that’s because, when we resort to using such terms—phenomenological, testimonial, postmodern, metajournalistic, and so on—it’s pretty easy to mistake the motivation behind experimental narrative journalism as purely a quest for “stylishness,” a desire to look avant-garde for its own sake. But in this Chapter, I will try to persuade you that experimentation in reportage often reflects a serious attempt to grapple with the the reigning assumptions about how we perceive, process, and depict experience. Some of our most experimental forms of narrative journalism are also, quite often, offering critiques of “standard” media practicies.

And sometimes reporters are compelled to invent new forms to meet seemingly impossible conditions. How does one “document” empirically, for instance, the horrors of authoritarian or totalitarian societies, whose very nature is to cover their own tracks, hide their own violence and repression? Or, how does one write about a postcolonial civil war where death has become so prevalent as to seem routine? Faced with such challenges, narrative journalists often re-shape their style to fit and reflect the conditions, the “givens,” of the nearly-impossible worlds they report on. In short, even the most experimental of styles can be born of necessity.

The Varieties of “Experimental” Journalism

But what would make a work of narrative journalism “experimental” in the first place? After all, there are lots of examples of the mixing of modes I discussed in Chapter 4: for instance, Tom Wolfe’s satirical, over-the–top “downstage narrator” (that is, where Wolfe throws his voice into the speech of characters), or Norman Mailer’s decision to make a mock version of himself in his New Journalistic masterpiece, Armies of the Night (1968). You can also find alternative forms of immersion reportage in the magazine writings of early-twentieth century female sociologists, writing about what it was like to be a waitress or a department store worker; encyclopedic, globe-traveling documentary works like William Vollman’s Poor People (2007), or moving novelistic accounts like Katherine Boo’s Behind the Beautiful Forevers (2012); experimental and yet still realist forms of Nature writing, gender crossover or disguise, travel and political criticism, and more.

However, some of the more significant examples of experimental narratives derive from a rather surprising fact: that many journalists feel that the conventional modes of everyday reporting, even those that can seem “realistic,” don’t actually reflect what its actually like to be “on the scene“–its “felt experience,” how “unreal” it can feel, or simply the actual, on the ground conditions that they face when trying to report.

What do I mean by that? Well, for example, perhaps they feel that the powers of an omniscient or third-person narrator are largely an illusion best left to actual novels. That is, in fiction, omniscience typically gives both the author and their reader the power to see things that no one actually has in real life. (We cannot, for instance, read others’ minds, or see into houses through walls, or see forward in time.) Likewise, third-person narration often comes with the illusion of the speaker or writer’s invisibility. (Or, as I said in Chapter 3, it can make us that we are looking at an event from an impossible Archimedean position.) Some reporters also feel that omniscience can play into an idealized notion of “objectivity” that isn’t credible or honest. As thinkers like historian Hayden White have argued for some time, the idea of a “disinterested” observer may well be a completely “imaginary” notion that, in some respects, goes hand in hand with old-fashioned empiricist thinking, or what White calls the “the illusion of a centered consciousness capable of looking out on the world, apprehending its structure and processes, and representing them to itself” (14).2 To many thinkers these days, this is merely a “reality effect” that doesn’t exist in the real world.

On top of that, using an omniscient narrator of a realistic narrative can easily create the impression that the author has full authority and control over what they are telling us. And yet, as David Shields has pointed out, it’s only in fiction that an author creates what a character is “really” thinking; there, we never question whether or not that is a “true” account of that thought process.3 But no journalist is actually a mind reader. “Facts,” indeed, might seem more unstable in journalism than they are in fiction.

The Example of William Finnegan

So what are some experiments that journalists take on? Well, some narrative journalists will try to create a quite visible, “character” out of themselves. That is, they create a narrative persona. That doesn’t mean they “make up” things about themselves, necessarily; often it means simply pointing to their fallibility–to their doubts, their limits, their mistakes of perception. Here, for instance, are the reflections of New Yorker staff writer William Finnegan, whose book Cold New World (1998) recounts travels across the United States, talking to at-risk teenagers and young adults in disadvantaged communities. What Finnegan says here has become his trademark–and a more authentic way to present himself:

[For me, O]mniscience is really not a possibility. My fallibility, my presumptuousness, have to be acknowledged … The right of the characters in the piece to tell their stories seems so much greater. I feel compelled to show how I am constructing the story, how my opinions are just my opinions, how the people I’m writing about may have their different opinions, and how this is all about not simply their lives, but my interaction with them–and their efforts to understand me.4

This move is not the byproduct of self-indulgence on Finnegan’s part. Rather, he chooses to re-create himself as a character in the story we’re reading, a figure who characteristically is represented as have reacted openly to the scene his text is describing—often, in fact, that character wears his thoughts and emotional reactions “on his sleeve.” Moreover, we’re constantly made aware of how Finnegan’s own presence might have affected the scene, provoked reactions in others, and so on (Something omniscience also prevents us from thinking about, often.). He also shows how his journalistic assignment often represented an intrusion in his subjects’ lives, as well.

Meanwhile, Finnegan also not uncommonly writes his stories denying the reader the kind of certainty and control of retrospection (and as I say in Chapter 3, the false foresight) that realism has made us accustomed to. Sometimes he does this by using the grammatical form known as the “historical present tense.” (For instance, he will write something like “I walk into the room,” rather than “I walked,” even though past events are being represented). The result is that the figure of the journalist is no “icon” of impartiality, as Janet Malcolm and others would have it, but someone human and fallible, even making it up as they go along. Indeed, as Robert Boynton has observed (78), Finnegan is more than willing to create a narrative structure that exposes gaps or contradictions in his own thinking, both at the time of his observation and in hindsight. (This is what are sometimes called aporia .) In other words, Finnegan intentionally shows the discomfort of privilege he often experienced. Other writers–Joan Didion and David Foster Wallace come to mind, immediately–take this representation of self-consciousness even further, often very intentionally letting us in on (to use Didion’s phrase) how they “feel,” or (in Wallace’s terms) re-appearing as a figure who follows the “imperative” to be constantly questioning what others actually in the scene being reported do not.5

If you re-examine Finnegan’s reflection above, you can also see that he simply wants to let us see how his story-form was built and researched—and moreover, to have his the story-form honestly represent his “take” on the actual subject relations he attempted to forge along the way. Reciprocally, he intuits that denying himself (and us) the privileged positions of omniscience and retrospection, even at the level of the narrative voice, is one way to create more story-telling space for those subjects themselves. (Think back to how Barbara Ehrenreich, as discussed in Chapter 2, may not do that enough.) Because journalists such as Finnegan have consciously worked to give more story-telling authority to their subjects, they get to say or think what they will—even react to him or contradict the journalist. (For instance, to the fact that the journalist is white, or an outsider, just there for a “story,” and so forth.) Quite often, this is also a matter of keeping the language or the “argot” (the particular vocabulary, patterns, inflections and subtexts of speech) of a subject intact and visible in what one writes, rather than constantly changing it into standard English or paraphrase. Here’s Finnegan again, from the introduction to Cold New World:

I’m particularly interested in how people understand their own situations. I tried to let them show me, when possible, where their story was and what it might mean. Some of the most eloquent commentary I found came, therefore…in jokes, asides, quarrels, incidents, display. I can’t think of a more nuanced expression…of the ‘double truth,’ as Benjamin DeMott calls it, “that within our borders an opportunity society and a caste society coexist’ than [sometime drug dealer] Terry Jackson’s decision to “go Yale..” [in a local New Haven parade]. . . It was dope,” Terry said afterward. Indelibly, I thought. (xv)

The Example of Margaret Randall

Considerations of the subject’s voice and perspective are also vital to a variety of experimental reportage I’ve been referring to as “testimonial” journalism. An illustration of this approach can be found, for instance, in the writings of Margaret Randall, who reported on Latin America (and particularly women’s experience there) for decades starting in the 1960s. Repudiating the standard practices of war correspondents from what she deemed imperialist countries, Randall instead took to likening her own work to the practice of oral history. Indeed she compared her reporting to what she called “reclaiming” the “lost” experiences of women transformed by war, forced to live underground in revolutionary times, or marginalized in cultures given to machismo.6 In famous works like Sandino’s Daughters (1981), Randall even took to printing snapshots of her subjects, and then transposing their memories into short, inset reflections cast in their own voice–as in this selection from a chapter entitled “The Women in Olive Green,” about female soldiers following the success of the 1979 Nicaraguan revolution:

Right alongside this particular photograph, Randall offers two different ways of framing it. The italicized selection below is from the unnamed narrator (we assume Randall herself); the second is the direct testimony of Randall’s subject:

This is Ana Julia Guido, a young woman with an honest face and strong body. She is dressed in olive green and carries a heavy pistol at her hip. The rolled-up sleeves of her army shirt revealed traces of the notorious “mountain leprosy” that was so common among guerillas assigned for long periods to the mountains. Ana Julia works in Personal Security, the office responsible for the bodyguards of the Revolution’s leaders. . . . ANA JULIA: . . . When I went underground I was sent to a training school in the mountains. It was given by Tomas Borge. We studied political, military and cultural questions. We also learned some basic nursing techniques. But the emphasis was on military training Monica Baltodano and I were the only women. It’s because of those classes that I’m the guerrilla I am today. Eight or nine of us decided to form a group in the mountains. The others all went to work in mass organizing, in the neighborhoods, or in the underground student movement. I was in the mountains for two-and-a-half years. (128 – 129)

Many readers will no doubt recognize that Randall’s technique is carrying even further the “mosaic” or scrapbook effects I discussed in my previous chapter—in a sense, literalizing those effects. In many moments Sandino’s Daughters looks like a collection of “candids” captioned by very personal, even intimate histories. Especially in Randall’s photographs, the bodies of these women, as females, are made larger and important, and the exchanges these ex-soldiers have with Randall often pivot on their shared understandings as women. In short, narrative journalism is presented as a record of a transaction that is itself is meant to testify to a forged political relationship between Randall and her subjects. At the same time, the subject’s voice is allowed to emerge, as if she is given more authority over her own memories (to decide what’s important seemingly without the journalist choosing it for her.) Randall seems to ask her U.S. audience to see her Nicaraguan women not as dangerous guerrillas, but as we would our own veterans, as returning home with new expectations and a new maturity. Their testimony, in turn, becomes something to cherish, again like a literal a scrapbook–much as, say, memoirs of war correspondents often do, by including photographs of comrades or soldiers. Or, as Dexter Filkins did in The Forever War (2008), when he included some work by the photographers who had accompanied him in Iraq and Afghanistan.

It would be unwise, of course, to read testimonial journalism or scrapbook effects uncritically, or to view the words of Randall’s subjects as fully “unframed.” Testimonial journalism can lure into thinking that we need not question the subject’s own story, or its authenticity–since it makes it look like we’re getting that story straight. (Or, to make the “news story” the same as the subject’s story.) But especially in partisan or politically controversial contexts, subjects often don’t just tell their stories unprompted, or without expectations about what their listener(s) want to hear–quite the opposite, in fact, is usually the case. It’s unavoidable, for instance, to wonder whether Randall ends up cropping her subjects’ testimonies much as she does the photographs that accompany them: even the verbal text alongside acts as a caption, interpreting the photograph for us. In the case of Dexter Filkins, meanwhile, the photographs he reprints aren’t simply “illustrations” standing on their own, un-interpreted, either; rather, we typically will compare them to the stories we read in his text. As if we are looking at another person’s scrapbook, we might well feel as if we are reading over the shoulder of Filkins himself. That is, these images are working as memory triggers to call up deeply emotional, personal responses in Filkins’s memory.

And then, of course, when we’re talking about representing “testimony,” there’s the entire complication of translation, say, from Spanish or Arabic to English. Even when a narrative journalist intends to cede story-telling authority to their subjects, translation comes in between. And in translation, of course, there is always interpretation.

Michael Herr and Postmodern “Illumination”

Finnegan’s and Randall’s desire to cede some interpretive authority to their subjects also takes us back to Michael Herr and “Illumination Rounds”—indeed, to the phenomenological experimentation in Dispatches that goes well beyond realism. In a general sense, much of Herr’s reporting is testimonial, too—though he expands that approach to become, as well, a “collector” of song lyrics, superstitions among his soldiers, and more. And much like other testimonial journalists, Herr wants to preserve the way soldiers talked, so as to demonstrate how they interpreted and experienced the war. Herr also lets us into the contradictory emotions he himself felt (fear, guilt, envy) as these stories were told to him.

However, Herr’s departures from realist conventions are even more experimental. For example, the memoir throws out the conventional linear, exposition phase of realist narrative–that is, Herr usually doesn’t bother to orient us to time and place, or give us the background we think we need. Rather, Dispatches is closer at times to lyric poetry: it turns back in time over and again, as if the war itself isn’t really going anywhere. Only in the second and third sections of the book, entitled “Hell Sucks” and “Khe Sanh,” does he give us moderately-chronological renderings of military campaigns. Instead, Herr reminds us that the “round” circularity of Time itself often defined this particular war. In one moment, Herr compares the war to a round “Mandela,” in that it repeats itself, and even when reporters are “backgrounded” that background starts “sliding forward” (49 ). Meanwhile, the American military simply repeats the mistakes of the French in Indochina; the repressed past returns in Herr’s present.

Some of these experimental techniques do seem to reflect the nature of this particular war. Herr’s pattern of dropping down into intense moments of combat or fear, and then lifting out of them again, was partly a byproduct of the signature technological feature of the war: the helicopters that were deployed in counterinsurgency and battle, engagement and rescue. When caught up in the visceral motion of the “choppers,” it’s easy to lose track of where we are. Moreover, given the way his soldiers (the “grunts”) talk, we can disoriented both by their military jargon and use of acronyms, and the way that their use of American history is so often turned into twisted private jokes. (The grunts call one bunker, for instance, the “Alamo Hilton” [123].) And of course there is a lot of tangents, too–especially complaints about the media in the book: dismissive asides about the “dial soapers” (commercial TV reporters [42]) accepting everything they hear from the military, or indulging in a “fact-figure crossfire” (50) of body counts. Herr also condemns the “Five O’Clock Follies” (99 ) of daily press conferences, which he calls “psychotic vaudeville” (215) that desensitized Americans to the violence and absurdity of the war.7

However, what really makes Dispatches experimental is how Herr writes about the relationship of consciousness, perception, and language. Like other postmodern writers, Herr does not believe human beings come to experience as blank slates. Nor are we ever—to return to Hayden White’s point—ever able to stand apart, able to capture events in our minds without distorting them. (The phenomenological approach, in this sense, might be thought of as the opposite of the Archimedean.) Rather, Herr believes we are already criss-crossed and permeated by prior images and experiences that deeply affect our perception and understanding. These images and prior experiences “hardwire” us to have certain physical, emotional, and even ideological responses. As a result, as we gather up the thing we call “experience,” we do so only through a filter of internalized and often deeply distorting concepts and feelings.

In other words, in phenomenological terms, whenever we think we are getting the very things that war correspondents value so highly–direct, immediate experience with combat, moments of individual heroism and valor, and so on—are actually liable to be perceptions deeply filtered through prior exposure to films or TV or even legendary stories from other war writers (e.g. the writings of Ernest Hemingway or Graham Greene). Indeed, experience can actually feel as if it is second hand, an eerie echo or comic knock-off of those images. (One soldier calls out in a crossfire, “cover me,” and everyone cracks up in hysterics [211]).

As many scholars have shown, Dispatches reminds us that the “reports” we are reading are dramatically reshaped by the tricks of memory, too. As in postmodern novels, memory commonly is not simply the holder of events as they actually are; rather, to Herr, the brain works like a camera or a tape recorder. Thus, a shocking memory is called a “memory print”(28) that stays in Herr’s brain; he refers to feedback loops (210), and constructs elaborate puns on journalistic terms like “background” or “contact”–or, in his most famous refrain, “I went to cover the war and the war covered me” (20). That simple phrase can give you a very good sense of the layers a phenomenological approach entails. Of course “to cover” is what a reporter does: cover the war. But in time, the word reverses itself, to mean it becomes part of, dominates over, the journalist as well, covering like paint or a tattoo or a collage of news clippings and photographs. Indeed, in music, another meaning of “cover” is to take an original tune and create another version; thus, Herr’s war is really “covering” or repeating every war before it.[2] The title “Illumination Rounds” itself refers to such effects. The phrase refers literally to “rounds” of ammunition that contain hot flares that illuminate a target, much as a strobe light will; in the context of Dispatches, the word refers to “illuminating” moments from the war, or something like film clips or, more likely, montage.

And finally, there are writers who draw upon the epochal transformations in the visual arts since the heyday of classical “realism” I discussed in Chapter 3. That is, at least since the arrival of impressionism or cubism at the turn of the 20th century, many painters have experimented with forms that, as David Hockney has repeatedly put it, “break the window” of the realist illusion and attempt to arrive at something closer to how human beings actually perceive the world while being in it.8 So let’s take a look at my final example of experimental reportage: Joan Didion’s controversial account of the Civil War in El Salvador, from the early 1980s. An account in which Didion uses many tools–collage, shifts in point of view, quite “unreal” landscapes–one finds throughout 20th century painting.

Joan Didion: Rethinking the Real

Some Context

Didion’s short, 108-page work Salvador (1983) resulted from a trip of just a few weeks in the early 1980s to report on El Salvador’s ongoing civil war. Originally, sections of Salvador appeared in the New York Review of Books. That the NYRB is generally considered a liberal journal is important. Although she had previously been labeled a conservative, largely because of her portrait of the 1960’s counterculture in her collection Slouching Towards Bethlehem (1968), Didion gradually found herself recoiling from the resurgence of the Republican Party in the 1980s. She resented the increasing elitism and public-relations emphasis of American political campaigns, manifested especially, she thought, in the administration of Ronald Reagan. Along with Nicaragua, El Salvador was one of the primary testing grounds of Reagan’s new, aggressively anti-communist policy in Latin America.

Reagan’s shift away from President Jimmy Carter’s platform of human rights in Latin America is vital to understanding the context for Salvador as well. Following the defeat of Carter in 1980, a still-Democratically-controlled Congress had imposed a set of conditions on Reagan’s campaign of increasing military aid to the government of El Salvador. Briefly put, Congress established a set of so-called “certification” standards by which the Reagan administration was required to verify (1) the curbing of human rights abuses by the military and private militias, (2) the extension of what was called “land reform,” or redistribution of lands held by Salvadoran elites to the wider populace, and (3) the establishment of free and fair elections. In the early 1980s, Didion arrived in-country, ostensibly to assess how things were going.

Didion’s Challenging Style

Nevertheless, anyone reading Salvador at the time with these expectations probably came away disappointed–as readers still may, even today. Didion can seem like she’s avoiding the very assignment we think she should take up. Instead, we are confronted with dense, highly stylized passages. For example, here is her opening description of the airport that she lands in, itself supposedly a landmark of the U.S-sponsored modernization underway in El Salvador. But she says that the airport only testifies to

a central hallucination of the [recent political regimes in El Salvador], the projected beach resorts, they Hyatt. . . tennis, golf, water-skiing, condos . . . the visionary invention of a tourist industry in yet another republic where the leading natural cause of death is gastrointestinal infection. In the general absence of tourists these hotels have since been abandoned, ghost resorts . . . and to land at this airport built to service them is to plunge directly into a state in which no ground is solid, no depth of field reliable, no perception so definite that it might not dissolve into its reverse. (13)

Didion’s assignment seems to be short-circuited even before it begins. She goes on to emphasize that that she had become too deeply terrified by the ongoing political violence to fulfill even the most basic of reporting duties. We see her failing to conduct a serious interview with the political leaders of El Salvador, or to travel out into the countryside to successfully assess whether the criteria for “progress” the U.S. Congress had set were being met. The actual physical terrain, regional differences, or political institutions of El Salvador can be nearly impossible to “picture” in her book. Didion repeatedly confesses that she’s moving about in a kind of “amnesiac fugue” (14); she includes long passages examining the intricacies of how bodies are disfigured by local militia groups; or, she speaks of staring ahead, “not wanting to see anything at all” (16), remaining in a spirit of “personal dread” (56). Instead she prefers to paste in verbatim snippets of speeches, or cablegrams coming from the US, or recount strange episodes that seem to stand apart from the supposed objectives of her own visit. And because Didion seems so absorbed by her own fearful state, El Salvador’s institutions seem dysfunctional, disabled, or nonexistent in the face of ever-present terror. Not surprisingly, Salvador calls up the literary spirit of Joseph Conrad’s “heart of darkness,” and lingers over the apparent indifference or numbed obliviousness with which the residents of El Salvador seem to view the litany of violence around them

Once again, to put it mildly, by foregrounding how she feels, she seems to struggle to make any sense out of what she is seeing. Here, for instance, is her description of the interior of the local Metropolitan Cathedral, where the famous opposition leader, Archbishop Oscar Romero, had been assassinated by government forces in 1980:

On the afternoon I was there the flowers laid on the altar were dead. There were no traces of normal parish activity. The doors were open to the barricaded main steps, and down the steps there was a spill of red paint, lest anyone forget the blood shed there. Here and there on the cheap linoleum inside the cathedral there was what seemed to be actual blood, dried in spots, the kind dropped by a slow hemorrhage, or by a woman who does not know or does not care that she is menstruating. . . .

The tomb itself was covered with offerings and petitions, notes decorated with motifs cut from greeting cards and cartoons. I recall one with figures cut from a Bugs Bunny strip, and another with a pencil drawing of a baby in a crib. The baby in this drawing seemed to be receiving medication or fluid or blood intravenously, through the IV line shown on its wrist. I studied the notes for a while and then went back and looked again at the unlit altar, and the red paint on the main steps, from which it was possible to see the guardsmen on the balcony of the National Palace hunching back to avoid the rain. Many Salvadorans are offended by the Metropolitan Cathedral, which is as it should be, because the place remains perhaps the only unambiguous political statement in El Salvador, a metaphorical bomb in the ultimate power Station. (79–80).

Readers can easily feel at a loss for what they are supposed to be learning here. In some moments Didion seems to fall back on unappetizing stereotypes about “the tropics” and its politics, or about Latin-American machismo. Indeed, Didion’s occasional moralism, or the ethnocentrism that sometimes mars her work, can also be very off-putting. Little wonder, then, that, of all Didion’s works, Salvador is probably her least-respected. To many, Didion had not only spent too little time in-country; she had also failed nearly all of her duties as a journalist–after all, a profession we commonly associate with taking risks; and, instead, she gives us a series of opaque and disconnected “mood” pieces that can seem narcissistic and even gratuitous in their voyeurism of violence. At first glance, she seems to fail at immersion, too.

Style, Feeling, the Dreamwork of Politics

Salvador may indeed never meet everyone’s personal standards for effective reporting. But if we come to this text with the expectations of a fully recreated “world” (or country) in all its dimensionality, we’re liable to be looking for something that Didion isn’t out to provide. So, suppose, instead, we start by re-looking at the experimental style of Salvador more directly.

Just as I did in Chapter 3, I’d suggest that one of the most useful ways to re-think her experimental style is to consider analogies to painting. For instance, if you begin by looking back at that description of the airport that greeted Didion upon arrival, or the one of the Metropolitan Cathedral, you might come to see that they are not “realistic” renderings in the classical sense discussed in Chapter 3. (They are not offering, that is, a neoclassical, proportional, or balanced illusion of three dimensionality.) Instead, the first passage about the airport, for instance, talks about the absence of a visual “depth of field”– the perspectival device so important to the tradition of realism–and even the absence of any “ground” that appears solid. Instead, Didion suggests that the images taken in by her eye become reversible and unstable–as, again, in a mirage or a hallucination.

Her description of the Cathedral, likewise, might seem more like a flat collage: Bugs Bunny cartoons, motifs about blood and IVs, drawings of babies with no known author. Didion emphasizes the sheer incoherence of her own journalistic materials, their degradation, and the way they resist logical explanation. And then, perhaps alluding to the Metropolitan Cathedral’s history, Didion’s eye moves away from the “unlit” altar to the National Guardsmen, doubtless signifying the agents of Romero’s murder, still watching over the scene. We might also notice that blood itself runs through the description. bombing If these are indeed “mood” pieces, their defining effect is the ominous, fearful awareness of the destruction of a site we otherwise might view as sacred, or as a locus of peace.

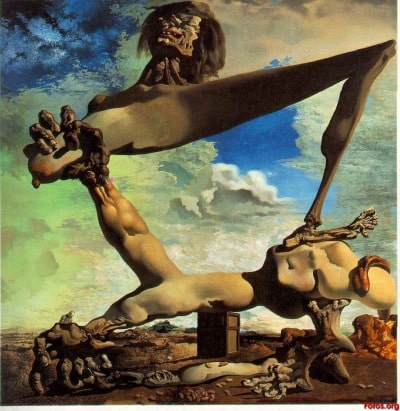

Now, there are many terms one might apply to the style of Salvador, and to those passages in particular. She refers (for instance) to Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s “magical realism” (53). Later, she compares the Cathedral’s ruins to the cold materialism of Brutalist architecture (78). And in seeing the destruction around her, she says she thinks of Pablo Picasso’s Guernica , not coincidentally just after her description of the Cathedral (79). (Guernica commemorates the German Nazi bombing of a Spanish community in 1937 during the Spanish Civil War.)

But of all the allusions to the arts Didion mentions here, perhaps the most mportant precedent is called up by the title of her book. Along with the religious allusion in her title, she is doubtless calling up the twentieth-century Spanish painter Salvador Dali, whose ways of picturing the world–as below–often meditated on civil war and global conflict in similarly startling ways:

In short, the possibility exists that Salvador, at least in part, is not so much a work of realism as what Dali and his contemporaries called surrealism.

Of course, we often use the word “surreal” colloquially to describe something that seems “unreal,” incongruous, out of place, or defying the laws of physics. Or, we often use the term “surrealistic” to refer to images representing a dream-like state–and certainly there are numerous instances where Didion refers to be being in a dream, nightmare, mirage or hallucination. However, suppose–as I have frequently asked my own students–we went deeper. Suppose we tried to dig into Dali and the actual Surrealist movement itself, and compare them to Didion’s own style?9

For instance, let’s begin with Didion’s decision to have her own emotional state permeate her reporting. Dali, as it turns out, was similarly interested in creating his paintings though a process of what he termed (in translation) “automatic writing,” or even inviting a “paranoiac” state in order to tease out the unseen in the present, or the portents of the future that could not be seen or verified in the empirical realm. Compare Didion, in an early scene in which she establishes the keynote of so much of what is to follow:

Whenever I had occasion to visit the Sheraton I was apprehensive [in a way that] came to color the entire Escalon district for me . . . I recall being struck by it on the canopy porch of the restaurant near the Mexican Embassy, on evening when rain or sabotage or habit had blacked out the city and I became abruptly aware, in the light cast by a passing car, of two human shadows, silhouettes illuminated by the headlights and then invisible again. One shadow sat behind the smoke glass windows of a Cherokee Chief parked at the curb in front of the restaurant; the other crouched between the pumps at the Esso station next door, carrying a rifle. It seemed to me unencouraging that my husband and I were the only people seated on the porch. In the absence of the headlights the candle on our table provided the only light, and I fought the impulse to blow it out. We continued talking, carefully. Nothing came of this, but I did not forget the sensation of having been in a single instant demoralized, undone, humiliated by fear, which is what I meant when I said that I came to understand in El Salvador the mechanism of terror. (25 – 26)

Here, Didion interweaves a physical location, an actual place, with the subconscious fears she felt on scene. And in turn, connecting her own paranoia–if that’s what it is–to the “mechanism” of authoritarian terror. As my students reported, Dali was similarly interested in more than merely “picturing a dream.” Rather, he was often making his canvases demonstrate how the subconscious realm permeated the visible world as well, suffusing social and political operations that others viewed as “normal.”

Didion uses a very similar effect to show how “dreamwork” is actually in charge of a supposedly “rational” political process like certification. Here is her description from an interview with a local citizen about land reform:

What he said was obvious, but out of line with the rhetoric in this conversation with President Magana about the Land-to-the-Tiller, which I had heard described through the spring as a centerpiece of United States policy in El Salvador, had been one of many occasions when the American effort in El Salvador seemed based on auto-suggestion, a dreamwork devised to obscure any intelligence that might trouble the dreamer. This impression persisted, and I was struck, a few months later, by [an intelligence report which showed that] . . . [t]he intelligence was itself a dreamwork, tending to suprt policy, the report read, “rather than inform it,” providing “reinforcement more than illumination,” “’ammunition’ rather than analysis.” (92)

Here, Didion suggests that American officials themselves are caught up in a kind of “dreamwork” that is directed by auto-suggestion. Or, compare her discussion of how bourgeois democracies orient themselves by using a political distinction (left/right), or speak of “solutions” (usually to other countries’ problems) but that has little resemblance to the object of its missions:

Whatever the issues that had divided [the people I interviewed], the prominent Salvadoran to whom I was talking seemed to be saying, they were issues that fell somewhere outside the lines normally drawn to indicate “left” and right.” That this man saw la situation as only one more realignment of power among the entitled . . . Was, I recognized, what many people would call a conventional bourgeois view of civil conflict, and offered no solutions, but the people with solutions to offer were mainly somewhere else, in Mexico or Panama or Washington. (35)

Naturally, my students have found many other suggestive links to Dali’s theories. For instance, my students often noted Dali’s interest, likewise, in creating different “quadrants” in his paintings’ canvases, perhaps a realistic-seeming ground in one zone of a painting, and then other quadrants where such realistic conventions were disrupted or abandoned altogether. We might say the canvas Didion has designed a similar canvas, meant to thwart realist expectations of that are cultural and political as well.

Perhaps, then, Salvador is not “El Salvador”

If so, why would she do that? Well, perhaps Didion’s Salvador might be read as a phenomenological text that retains a political edge. That is, perhaps Didion means to create an account which goes beyond the standard conventions of immersion–diving deep into an “underworld,” say, as the heroic reporter–and instead recount how her own conscious and subconscious mind was victim to the distorted perceptions and destabilizing effects of El Salvador’s political climate and violence. To the extent that Didion’s fugue state seems self-induced, it may be, as with Dali, something that the perceiver (Didion) invites into herself. While also trying to capture its surreal engagements with the U.S., Didion is also intent, I think, on passing her shadows and fears onto her American audience’s reading experience: the feeling of not really knowing when a real threat exists or whether it is merely one’s own paranoia. A soldier with a gun standing in the shadows may only be a shadow.–as Didion puts it above, this is the “exact mechanism” (26) of terror.

A few final points:

First, of course, much of I am saying above bears upon Didion’s rather unconventional political interpretation–one that doesn’t simply fall into “right” or “left.” Here, I don’t simply mean that she probably chose the Guernica-like interior of the Metropolitan Cathedral because of the long-standing associations of Picasso’s painting with the Nazi destruction of the Spanish Republican forces in Spain’s civil war. Rather, she wants to show us how the “Mission” of U.S. foreign policy is flawed. For instance, she is clearly playing with the connection between Salvador and the eclipsed “salvation,” religious or political, that might come from within El Salvador itself, or travel down from the U.S., in the guise of religious missions or political ones. Meanwhile, Didion’s book is not called “El Salvador”–it does not put the definite article on the place-name we expect, more conventionally, from realistic works of narrative journalism. In fact, Didion once uses “salvador” (as in “el salvador del Salvador” [29]) to pun on Ronald Reagan’s policy objectives—the Reagan who, in a characteristically surreal moment, also appears in movie playing at a local in-country festival. In our political culture, in other words, perhaps this is all but a phantasmic projection of our own political life, including our recurrent failures in Latin America.

I would even speculate that perhaps Salvador is not really depicting the place we call “El Salvador” at all--that is, the physical or geographical place we think we know or could assess. Rather, as in a Dali painting, it is more that Didion places her reader down into a collage, in the sense of causing us to lose ourselves in those decontextualized, indented snippets and stories that come from speeches or public relations or political “intelligence.” The sum effect of such floating snippets is that they ask us to re-examine a set of rhetorical exchanges that have moved North and South across the hemispheric divide, each becoming stranger to the other. In that way, Didion tries to show us–in a way challenging the left as well as the right– the simple improbability, in her view, of arriving at facts or measurable standards in such a political climate. And as such, she tries to show us the limitations of the conventional empiricist assumptions behind reporting more generally—the idea that facts or stories can be “gathered up” simply by being diligent and relying on one’s sources (especially “official” ones who are caught up in the Mission’s failure).

Our own tastes, of course, may be for more concrete reporting, more testimonial emphasis, and so on. Both Didion and Margaret Randall were trying to speak back against the distortions they felt dominated press coverage of Latin America. Randall’s goal is to show the ordinary lives of women hoping to use the Nicaraguan revolution to combat the machismo and discrimination in their own culture; Randall wants to make her women in olive green more familiar to U.S. readers, make their aspirations recognizable. And to help the women themselves recover and respect the importance of their own experience, as women, in the Revolution itself. Didion, by contrast, chooses to accentuate her vulnerability—the goal is to present the frightening horror of “disappeared” peasants and political violence. Even minor but devastatingly disturbing details in Salvador, like swimming pools that never have swimmers, or hotels that still have bullet holes in the wall, show us the scars of violence and authoritarian rule. If for very different political ends, these two reporters emphasize elements that are typically erased in, or put in the background of, dispatches sent out by correspondents so that more familiar political and military “actors” play their parts.

In this roundabout way, in fact, Didion’s decisions about her style and story-form might make a certain amount of journalistic sense. If one believes, as Didion clearly believes, that a given politician is a psychopath, or a fascist, politely asking him for information to “get the story,” or as a way to somehow certify ongoing progress in the region, seems absurd to her. For her part, Didion felt that the political setting of a place like El Salvador was so rife with propaganda, public relations, and political cover-ups that one could not assume anyone, or any group, was actually who they said they were. In these lights the U.S. Congressional certification process was itself a farce. What she was there to measure, in other words, in empirical terms—well, in her view, it didn’t really exist. In this way, by showing us honestly how “she felt”–and by capturing the terror that permeated even her role as a narrative journalist–perhaps she did her job, after all.

(An Afterword and Glossary section follow.)

(Note: if you’re interested in exploring Didion’s interests in modern and postmodern painting and architecture, this site has a classroom exercise devoted it–entitled Didion and the visual arts.)

Notes

- For the interview where that confession took place, see Paul Ciotti, “MICHAEL HERR : A Man of Few Words : What Is a Great American Writer Doing Holed Up in London, and Why Has He Been So Quiet All These Years?” Los Angeles Times 15 April 1990 ↩︎

- Hayden White, “The Question of Narrative in Contemporary Historical Theory,” History and Theory 23 (Feb. 1984): 1-33. ↩︎

- David Shields, Reality Hunger: A Manifesto (New York: Vintage, 2011). ↩︎

- As quoted in Robert S. Boynton, ed. The New New Journalism, p. 90. ↩︎

- Didion’s famous reflection appeared in Slouching Towards Bethlehem (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1968), 13.I have also relied on the insights of Josh Roiland, “Getting Away From It All: The Literary Journalism of David Foster Wallace and Nietzsche’s concept of Oblivion,” in The Legacy of David Foster Wallace, ed. Samuel S. Cohen and Lee Konstantinou (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2012) ↩︎

- Especially helpful is Margaret Randall, “Reclaiming Voices: Notes on a New Female Practice in Journalism,” Latin American Perspectives 18 (Summer 1981): 103-113 ↩︎

- For my discussions of the techniques in Dispatches, I have relied especially on Maggie Gordon, “Appropriation of Generic Convention: Film as Paradigm in Michael Herr’s Dispatches,” Literature/Film Quarterly 28 (2000): 16-27. ↩︎

- Hockney as quoted in Lawrence Weschler, True to Life: Twenty-Five Years of Conversations with David Hockney (Berkeley: U. of California Press, 2008), p. 31-33. ↩︎

- Many of the ideas in following derive from Ades Dawn, Dali and Surrealism (New York: Harper & Row, 1982), and Felix Fanes, Salvador Dali: The Construction of the Image, 1925-1930 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007). ↩︎