“News is not what happened, but a story about what happened.“

–Robert Darnton

Guiding Questions for This Chapter

What do American journalists typically mean when they use the phrase “the story”? And what other definitions of that word “story” bear upon the dimensions of narrative journalism that I introduced in Chapter 1? Let’s start this way: by imagining you’re back in the 1940s, in a world of gangsters, old-fashioned police cars, and tabloid photography:

A Reporter Looking to Get the Story

Shots ring out in an alley on a cold winter night, and a body falls on a city pavement. Someone thinks to call the police, and in due time they indeed roll up in black & white patrol cars. They push a few early onlookers back, bend over the body, and then begin to roll out the yellow “CRIME SCENE: DO NOT CROSS” tape. They do so because, as the great American journalist Stephen Crane loved to say, albeit with a wink: “a crowd gathers.” And imagine, if you will, in and through that gathering crowd walks a stubby, trench-coated man in a floppy hat, smoking a cigar, carrying a big box camera with an enormous flash that rattles the night. He’s elbowing his way to the front, crouching down, capturing the glint of his own flashbulb off the graininess of the pavement: snap, flash—the illumination races down and over the body, filling the alley for a split second. In the flash, you glimpse a steel-black revolver lying inches from a lifeless hand.

The photographer returns to his 30s-style Chevrolet sedan parked illegally, on the other side of the street. From the photographer’s chatter with the cops, you realize that he’s intercepted their radio calls at his own apartment—a greasy grim place that you later hear that he has wired to connect to the police dispatcher. He will, in fact, produce one of most famous “crime scene” photographs of this kind–an image sometimes known as “Hell’s Kitchen.” And yet, through it all, the odd man is also cursing under his breath. You see, he’s angry that he arrived too late again. In fact, he didn’t want just another “crime scene” photograph. He wanted to be there as the bullet arrived, before the body had fallen.

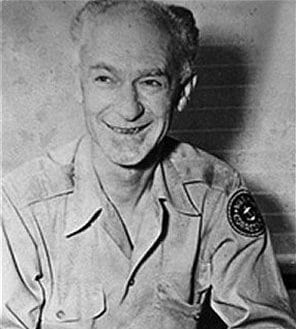

The odd man of this scene I’ve just described—a character who later became the centerpiece of an X-files episode, and had an exhibition at the Getty Museum in Los Angeles devoted to his work–is, of course, “Weegee” (Arthur Fellig), the famous tabloid news photographer from the 1930s and 1940s.

Fellig gave himself the name “Weegee” to remind others of a “Ouija” board, and thus to speak to the desire I’ve mentioned above: the hope that, someday, he could be present not to the aftermath of a crime, but to the moment the crime originally happened. He dubbed this fantasy “psychic photography.”1

“The Story” as Reporters Will Usually Define It

As odd as it may seem, however, in fact Weegee’s dream is only an exaggerated vision of the desire often at the heart of modern journalism: to get “the story,” the catchphrase reporters use. Indeed, in many ways, photography itself came of age alongside modern journalism’s quest for public legitimacy. The authority of a news photograph, that is, lies in what we call testimonial authority. Documentary photographer Jacob Riis (whom I will discuss in Chapter 4) even identified the flash of flash photography with evangelical illumination and truth itself—a light brought into the darkness of poverty or crime. Indeed, it’s often said that a photographer seems to make the photographer, or the reporter, disappear: it’s as if we become the witness.

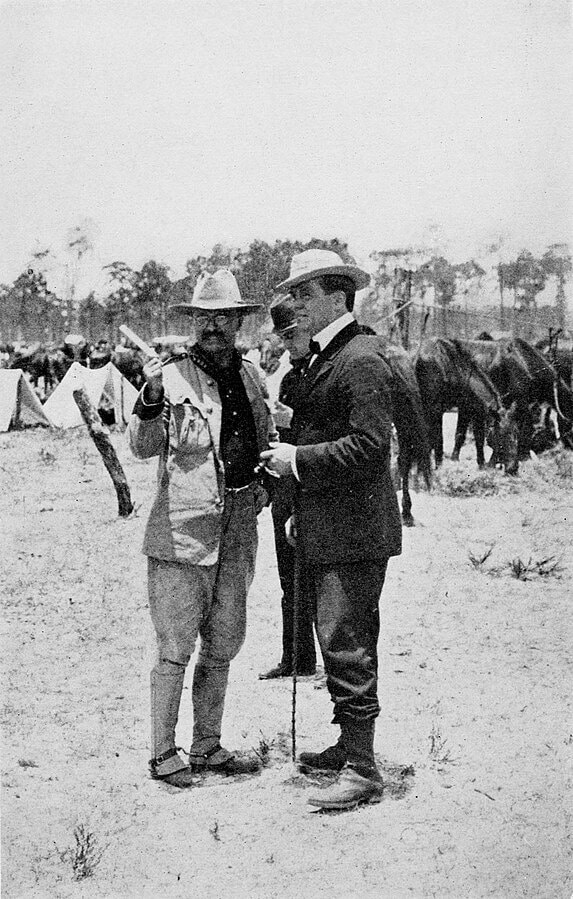

Young reporters are often told by their boss to “get the story,” and whether they do or not can often decide whether they keep their job. And by “the story,” journalists habitually refer to the element in an event that has the most news value, the element I have been calling the “news content.” Reporters talk about having a nose for news; in the 19th century, U.S. foreign correspondents were in fact sometimes called “news hunters” or “news gatherers,” as if a story was something to be tracked down like a lion. Here are some different images of American war correspondents over the decades that capture the identification of the reporter’s craft with exploration, adventure, or performing something like a soldier’s duty:

The word “Story,” however, has Other Dimensions

But for starters, we should notice that the word “story” doesn’t have that single meaning. For example, a family member or a teacher may read us “stories” in the sense of fairy tales, adventures, or fables. In this second sense, that is, a story is a narrative–as I said in Chapter 1, a collection of episodes put into a particular sequence, and seen from a particular point of view.

So there’s an important tension: journalists themselves usually speak of “the story” not as the narrative form into which their reporting will be inserted, but to the set of facts, testimony, and witnessed events prior to the choice of narrative form. In other words, reporters talk about going out and “getting the story,” because—or so it seems–they believe it exists in events, not in the means by which such events might be told. When cultural studies scholars and media critics refer to mainstream journalism’s assumptions as “positivist” or “empiricist ” norms, this is usually what they mean: that a reporter feels a story is something “out there” that they can gather up.

Meanwhile, there is a third dimension of “the story” that also gets into the mix. This is suggested by the colloquial way Americans use the word “story,” for example, when they meet someone for the first time: they say “so, what’s your story?” Or, if we’re confused about the way someone is reacting, Americans will quizzically say, “what’s their story?” In other words, Americans use the term “story” to refer to someone’s background or life history, or more commonly to something like “where did you come into these events?—how are you connected to them?” and “how would you tell it?”

Now, it might seem that this third meaning has very little to do with our first two meanings. But in fact, a good reporter is always asking people to tell their story—to tell the journalist who they are, or what their version of events is. In journalistic circles, this is referred to as the “subject’s” story, with again the “subject” being the person (or persons) directly involved in what will be reported. Even though journalists want to be direct witnesses, they more often arrive, like Weegee, after the bodies have fallen.

However, there is yet another, final sense of “story” that is connected to what we normally call “legwork.” Sure, we can reconstruct on our own how writers have conducted their research; sometimes we have to do that, because a reporter writes in a way that deemphasizes their own role or even seem “invisible” to us as readers. But in many other cases, works of narrative journalism often feature the journalist as a “character”–and even when they don’t, they often implicitly suggest how the journalist researched and reported their narrative. For example, they tell us about riding on helicopter, or say “when I met the General in Baghdad two years later,” and so on. Even when they’re not depicted in the narrative, we understand that they’ve often formed very close relationships with the subjects (the people) they’re reporting on.

Now, I’ll admit, this last point can seem like pretty minor stuff. But whether we like it or not, many of the finest works of narrative journalism read very much like a memoir. Sections of Michael Herr’s Dispatches, for example, originally appeared in Rolling Stone and Esquire magazine. However, the book version is looking back on what it was like to be a reporter in that war: it tells us about what it felt like to ride a helicopter in Vietnam, the temptations and risks to be a voyeur, and about the “personal movie” about heroism and masculinity that Herr confesses was in his own head at the time. (And after that time.) And so, by reading Dispatches, we learn something about how Herr collected stories, where he traveled, which events he witnessed, even—as various critics have said—about how his own memory worked.

Likewise, whenever a reporter writes in the first person, we’re getting an account of how they tracked through the story that we are reading. Barbara Ehrenreich, as I will discuss below, gives us a first-person recounting of her journey as a reporter in Nickel and Dimed: On (not) Getting By in America (2001), about why she made her decision to start in Florida, to adopt an undercover identity, and seek out employment as a low-wage waitress and hotel domestic worker. In other words, as she writes her story of low-wage work, she also recounts her reporting strategy and experience—the two are actually tied to each other in the book that we read.

As I’ve said in Chapter 1, one way to think about this is to imagine the literal footprints a reporter leaves in the text. It also sometimes helps to think of a perimeter or horizon line around your reporter. In real time, a reporter can’t be everywhere. So, what were the possible limits on how far they could see?—and what might have fallen outside of that horizon line? How is that horizon recreated in the narrative itself?–or is it transcended, somehow?

As we’ll see, there are many other questions one might ask about this fourth dimension of the “story:”

- what kinds of research, direct witnessing, or legwork contributed to the narrative?

- where does the reporter say they went?

- Who was interviewed? What was the pattern or routine of information-gathering established by the reporter?

- How, and how fully, did the reporter immerse themselves in the scene, or the group of people within the story?

- Did a reporter show us their tracks, or cover them, in the final written product?

- What kinds of emotions is the journalist sharing with us, now? How much of the journalist in the text seems like a persona, a kind of mask worn at the time—or even created for what we’re reading?

Looking for our Four Dimensions

As discussed in Chapter 1, it helps to think of a work of narrative journalism as an intricate lens that has been constructed by the journalist–a lens that asks the reader to focus on some things more than others.

There’s a lot that goes into making the lens. As I’ve jusst shown, narrative journalists make many decisions about how their project should be designed: choices about reporting strategies, the story-form to choose, how candid to be about their own experience behind the central tale they tell. Pay attention to those choices, and to the “balancing act” behind them.

Just as with legwork, there are many choices about the story-form the journalist chooses to put that legwork into. Among them:

- Where to start the story, in time—how far back to go?

- How many major characters to include?

- From whose perspective will the story be told?—and with what “point of view” (first person, third person, and so forth)?

- Did the reporter make themselves into a character in the story, and why?

- Where did the journalist choose to end the story?

And then, if we can, we try to think about the possible rationales that the journalist used to make the choices they did—what the advantages are of going about it in a certain way.

Be willing to Ask “Why”

As you go through a list like the ones above, be willing to ask “why” about things that may seem obvious at first: that is, why your journalist made the choices they did, and how those choices shaped the text’s lens of interpretation. Let’s take, for example, a book I’ve already mentioned–Ehrenreich’s Nickel and Dimed.

A highly popular work of investigative journalism, Ehrenreich’s book tells the story of going undercover as a waitress, Wal-Mart worker, and maid, in order to explore the world of low-wage labor in the late 20th century United States. So probably the first reason we read such a text is for its news content: to discover what it’s like to be one of those low-wage earners: how your boss treats you; what kinds of skills you have to master; and whether it is even financially possible to sustain a decent way of life. And so, maybe we’re taking notes not only about facts and statistics that Ehrenreich gives us, but her personal account of how hard she had to work, manage a budget, and so on. In other words, she is trying to create a portrait of that social class.

But take some of the choices behind her tale. For instance, we might ask why Ehrenreich chose to write her book in the first person (using “I”)–and what its consequences are for how she interprets service work. Well, one effect of a first person narrator, of course, is that we get access to how the journalist’s thinking—it’s a way that we get inside her head and even how she says her body feels, as well. Ehrenreich’s choice to use first person, therefore, is designed to give us access to her own psychological and physical responses to low wage work—the aches and pains she felt in doing the work.

Secondly, precisely because it is a first person account, we get pretty full accounting of the fourth dimension of her story: her legwork and its “footprints.” We learn her research decisions about why she started in Florida, chose to adopt an undercover identity, and seek out employment and so on.

Of course, there are other things we might notice about Ehrenreich’s narrative style beyond first person narration. (You might want to look quickly at this Checklist, too .) For instance, we might ask ourselves why Nickel and Dimed, while taking up such serious topics as exploitation and poverty, chooses to be funny at various points—to seem like a series of mishaps or misadventures that you might find in the works of Mark Twain or Miguel de Cervantes. Did Ehrenreich makes this choice just to be “entertaining,” or what?

To get at that question, here’s a next step: let’s start to read the story-form for its literary language – for its metaphors, similes, allusions, and so on. Doing so really can clue you in to the journalist’s interpretation. For example, in The Warmth of Other Suns, Isabel Wilkerson compares the Great Migration of African Americans to the North to the famous “middle passage” during the slave trade; to immigrants crossing an ocean, and envisioning a “promised land”; even to traveling between planets. These metaphors invite us to make comparisons, and to look deeper into what the analogies suggest. Likewise, when Ted Conover compares unlocking the cell doors of a prison to opening a “Pandora’s Box”—as he does in his account of going undercover as a guard in Sing Sing, Newjack (2000: 9)– it becomes clear that he means the prison is like a box where the world has put all its troubles, and that one invites great danger if one opens it up. Such imagery not only enhances the emotional impact of what we’re reading, or makes it entertaining; it also interprets for us by saying the thing we’re reading about is “like” something else.

So: how would we use those two aspects–the humor of the book, and its literary language–to dig into Ehrenreich’s interpretation? For starters, if we look at the name Ehrenreich chooses for her own character in the book, which is “Barb”—of course it’s literally her nickname. But we read for the literary pun, we might also notice that her narrative voice is full of “barbs,” or sarcastic comments. That’s a big reason why she chooses to be funny–she’s creating something of a satire. Indeed, a literary historian would recognize her story-form as a modern variation on satirical writing that is often called the picaresque: originally, a “misadventure” story, usually comic, through which we follow the misfortunes of a often naïve character trying to cope with failing social institutions. And that comic framework connects to the serious issues raised by other imagery, too. For instance, when she titles her first chapter “Serving in Florida,” we might start to realize that by “serving” she means not only “working in the service industry,” but “serving” in the sense of feeling like a servant, or even being imprisoned (serving a sentence). Indeed, like a novelist, Ehrenreich will soon extend her metaphor, even compare “serving” to being overtaken by an invading spirit or disease: “[S]omething new—something loathsome and servile—had infected me” (41), she will eventually write. That’s how her interpretation of service is starting to take shape.

Adding in “the Subject”–and being willing to Speculate

As we start to fill out Ehrenreich’s interpretation, we might start to ask: who are the subjects she’s writing about? Maybe we might make a list of her central characters—and ask what then do we really know about them? What do we learn about their backgrounds, or their beliefs? For instance, do they feel like servants?–do they feel “servile”?

That is, in some journalistic story-forms, subjects are made into seemingly complete and rounded “characters” whose names and backgrounds and opinions are shown to us (that’s something like a conventional novel). Or, sometimes they are simply sources of information whom we don’t see in depth; and sometimes they are placed completely offstage. Sometimes they are given big speaking roles; other times, the journalist chooses to speak for them. Sometimes you’ll be able to gather up the actual testimony of those subjects–in effect, using moments they are quoted, asking yourself how those subjects would interpret the story our journalist is telling. Sometimes you may have to do a little bit of creative imagining of what those subjects might say about their lives or experiences.

Or, if you have time, you might watch YouTube videos on being a service work, or documentaries on the tourist industry in Florida. Or, you might look at The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics on service wages, unionization, regional variations and so on. Maybe you try to find out what Walmart’s so-called “Associates” are paid, how many other jobs they might be holding down, whether they’ve tried to unionize or not.

And again, all of the above also connects back into the questions one might ask about what I’ve called the fourth dimension, or the story about the journalist’s own journey. Yes, we’re looking at legwork: Who was interviewed? Did you think that reporter was working undercover, in a disguise? In real time, a reporter can’t be everywhere. So, what were the possible limits on how far they could see? As I will be emphasizing in Chapter 5, you can also profit by looking closely at what I like to call the “on the ground” conditions that shaped the reporting that was even possible. By this phrase, I mean the prevailing conditions within a news event that

- shaped or restricted the flow and availability of information;

- structured what kind of access journalists had to the stories they sought, and the people telling those stories; -and-

- tried to influence the reporter with its own stories and/or angles on the events being investigated.

That is, narrative journalists very rarely enter into open terrain where they can go where they please. Imagine the police’s control of the Weegee’s crime scene: consider the police tape, the withholding of a victim’s name, the original source of the gun, and so on. Or, imagine a war zone: where reporters can go is often explicitly controlled by armies, or affected by damage to roads or buildings or by the dangers that come with warfare. Imagine a courtroom, where defendants are not allowed by their lawyers to speak to the press, and trials themselves have strict rules for kinds of evidence that can even be discussed. And so: what have those conditions allowed the reporter to see? And what has a reporter been prevented from seeing? How has the reporting strategy, which responds to conditions on-the-ground, shaped the journalist’s interpretation?

What was the meaning of the journey–for the journalist?

And here’s an even trickier part: you might start thinking about “what the story meant” to the journalist, too. You might think of this as a “back story,” or “story within the story.” The story you may be reading may be about what it’s like to live in poverty, fight a counterinsurgency campaign, or cross a border as a migrant. But it may also include a back story telling you where the reporter comes from, where they traveled to, to whom they talked, the decisions they encountered along the way, and so on. For instance, you can learn to read the Acknowledgements page, the “Notes on Method” the journalist includes, or authors’ prefaces, and listen to what journalists say about how they built their stories. (Several of these statements are available in the Authors’ and Practitioners’ Video section of this site.) Or go online on your own, and see if you can find an interview, or see a reading the journalist has given. Paying attention to the backstory can reveal things about the emotional investments the narrative journalist made, the costs or sacrifices that went into the project as a whole. And perhaps even the changes the reporter went through.

That’s a lot, I recognize. But the real payoff, I hope to show, is learning how to start putting these dimensions into conversation with each other.

How these Four Dimensions Can Interact

You’ll notice that I’ve already called these four dimensions of the “story” a “balancing act”—and here’s why: sometimes those dimensions work together, but sometimes they can compete with each other. Just as when you build a house, for example, there are going to be setbacks and compromises made along the way, and the final product may reflect them: a window that’s a bit too drafty, a room that seems shoehorned into the overall design, and so on. For example:

- Perhaps you’re left feeling that a journalistic subject in the tale wouldn’t like the interpretation the journalist is using;

- perhaps you gather up the kind of research the reporter did, and it seems incomplete;

- perhaps you think a particular literary choice the author made (e.g. deciding to leave themselves invisible to the tale) is a mistake (in this case, hiding what influence their presence may have had).

Again, the lens reporters create, the choices they make about form and legwork and the rest, can produce focus and clarity, and yet some areas that can be blurry or unexamined, as well. And with any narrative framework a reporter creates, certain things will fall outside the lens. You can learn both to appreciate a text and see some of its limitations. Media scholars sometimes use the term “framing”—which is helpful because a “frame” (or cropping) places limits and emphasis, too, just as it will on a photograph or a painting. Whatever analogy you find most helpful, the best ones help us realize that stories emphasize particular subjects at the expense of others, create chains of causation and call upon our sympathy, draw conclusions and suggest future repercussions.

For example, if a war correspondent writes a book about the U.S. Marines by focusing on a particular battalion, that choice might well give us a close-up vision of wars that our political leaders don’t often provide us. David Finkel’s The Good Soldiers (2009), for instance, shows us how such a battalion had to implement the so-called “surge” in Iraq, the civilian-management skills they had to learn to complete the mission, so on. At the same time, you might ask yourself what insights derive from the decision to write from the vantage point of foot soldiers rather than, say, generals or Pentagon officials. And what, alternatively, would talking to generals (or Iraqi citizens) have shown us—or overlooked—about such strategies? And so on.

Or, let’s take another look at Nickel and Dimed, starting with its central point about the supposed “servility” of the workers Ehrenreich examines: that is, she argues that they seem too ready to lay down on the job, not fight their bosses, much less form a union. Or, you might say, they keep their “barbs” to themselves, unlike Ehrenreich’s smart-alecky first-person narrator. But of course service workers aren’t exactly like servants, are they? Or, perhaps you can come at your critique through Ehrenreich’s choice to use that smart-alecky first-person persona of “Barb” as her narrator. In part, she uses her nickname to keep reminding us about her own birth family’s blue-collar identity. But it also works to contrast the supposed passivity she believes she has seen in her low-wage-worker peers in restaurants or at Wal-Mart. The identity of the narrator therefore becomes part of the argument Ehrenreich is making. (If you need to, read that sentence again.) In addition, her satirical stories about smoking rules and bathroom breaks are fundamental to describing the parameters of class warfare on what used to be called the shop floor. In other words, if we look into the literary effects of her story-form, we can better appreciate the many layers and nuances of her argument.

By the same token, however, we might see possible drawbacks, as well. For instance, the first-person point of view ends up making Ehrenreich herself, quite often, the dominant center of her narrative. As a result, though, we don’t hear all that much from her fellow workers, and we also don’t get very full biographies of their lives. Another journalist might have approached this same news-content (low wage work) differently—say, with a third-person interview technique that might have ushered more voices from those workers into our view. We might have learned how many immigrants come to be hired, something also neglected in Nickel and Dimed.

And so, it’s a little like taking the four dimensions “on” individually, and then seeing how they work together. And in doing that, you also start to think about how it all might have been done differently. That’s how you arrive at an active, critical reading that combines empathy and critique. You’re not out to “cancel” a book or a writer–you’re attempting to arrive at a balanced sense of their strengths and weaknesses.

In all, the conflicts between reporters and subjects, the events they report on and what they write, are often intrinsic to the four dimensions of narrative journalism itself, but not reducible to “subjective” feelings or points of view. (You might also want to see my “Short Take” entry on “subjectivity and objectivity.”) Those conflicts often derive, as I’ve been saying, from tensions between the different interpretations that exist in the very idea of what “the story” is–that’s the central point of this Chapter.

Some Takeaways

So: again, what does it mean to read in 4-D? To begin with, I can certainly recognize that I haven’t answered all the questions you might have about a given work. As I’ve said, sometimes you’ll have to go outside the text you’re reading to answer them. For instance, you can read another work on the same topic. Just as I would never recommend watching one TV news outset or reading just one newspaper, I’m always saying you can really see a writer’s interpretation of a given topic (poverty, colonial war, migration, etc.) if you see another journalist’s angle.

But maybe you’re saying: OK, perhaps I can see that these dimensions of narrative journalism exist, but how do I keep all these dimensions in my head?

Well, probably no one can. Often it’s more a matter of exploring the relationship between two or three dimensions.The point is that each of these dimensions works in tandem with the others, and any one of them could have been undertaken in a different way

That’s why I started this Chapter with Weegee. Because Weegee is arriving at the crime scene after the body has fallen, his photographs can’t really “gather up” everything about his crime scene. A photo can’t capture, for instance, the “why” behind the killing, nor the motives, nor even the particular sequences of time when it all went down. But writers of narrative journalism, faced with a similar problem, can use investigation to move their stories back in time; they can interview people, and reconstruct the things not directly seen. So knowing when a writer came into a story can show you where they were engaged in that reconstruction; likewise, understanding that “horizon line” established by point of view can help you think about where else a reporter had to—or should have—gone to “fill out” their story. As I hope I’ll be making clear in my next Chapter’s discussion of Alex Kotlowitz’s There Are No Children Here and John Hersey’s Hiroshima, writers are often quite strategic about where and when they start their narrative and the angles they want to create by choosing certain points of view, or creating certain collaborations with certain subjects and sources.

And that’s the final takeaway. While it’s important to “take in” and empathize with your reporter’s goals, it’s just as important to look for gaps, blind spots, trails un-followed. You see what is “covered,” but also what gets left out, or gets less emphasis or falls between the cracks. It turns out that, as you perform these critical tasks, you discover that there are actually many “stories” in any given work of narrative journalism. That’s usually what makes these books even more engaging.

In the next Chapter, I mean to take up the question of “how realistic” a work of narrative journalism can seem–and the different ways it creates that feeling.

==============

A Study Sheet on Reading in 4-D

Notes

- For an overview of Weegee’s career, see Miles Orvell, “Weegee’s Voyeurism and the Mastery of Urban Disorder,”American Art, Vol. 6, No. 1 (Winter, 1992): 18-41.[2]. The Macdonald case, and Malcolm’s own treatment of it, is also the subject of Errol Morris, A Wilderness of Error (New York: Penguin, 2012), and Kathy Roberts Forde, Literary Journalism on Trial (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2008). Part of this section appeared in my “The Journalist Who Was Always Late: Time and Temporality in Literary Journalism,” Literary Journalism Studies, vol. 10 no. 1 (Spring 2018): 113-138. ↩︎