Can you use “close reading” when analyzing Narrative Journalism? The Answer is Yes–with a few Twists

What is “Close Reading,” anyway?

Over the years you’ve been in school, maybe especially in English courses, you’ve probably been taught, over and again, the importance of so-called “close reading.” It’s a term that has a general sense, and a specific one. In general, it refers to paying close attention to details, figuring out what a writer is implying rather than just saying “out loud,” and keeping an eye out for general themes or motifs–ways that a writer pulls together a longer work. It’s hard to imagine any reason not to go about this general sense of “close reading” when you’re reading narrative journalism.

But you probably know there’s a more specific, technical sense of “close reading” as well. Here, the phrase refers to a particular way of intensive reading that is sometimes called “exegesis” or “explication,” and it’s famously connected to the school of interpretation known as “formalist” reading. Close reading in this sense means something more like

- teasing out the patterns in the figurative language and imagery of a literary text, so as to

- describe the relationship between the design of that text–the point of view the writer used, its dramatic structure and so on–and

- the broader ideas, associations, and connotations that are embedded in its language.

A close reading is typically demonstrated or “performed” by an intensive, extended reading of a selected passage.

Close reading is a mode of “analysis,” a word which often means simply breaking down something into its parts--like, say, a car engine–and then showing how the parts work together (as in how a fan cools an engine when it gets hot so that it keeps running without boiling over).

The reasons your teachers emphasize this more technical sense of close reading are, of course, various. Mainly, it is thought to be a way to have you arrive at something more than just a personal response when you read, or to “build out” on that reaction–something you may sense is going on but need to explore more deeply. Instead of just liking or disliking a story or style, or jumping prematurely to a connection to your life (e.g. “this description reminds me of something that happened last summer”), you’re encouraged to first “think like the writer” and imagine how that writer designed the text with certain patterns that allow you, if you “read closely,” to understand more of its the journalist’s ideas, the larger context, what’s “complicated” rather than what’s simple. (So, for example, you might notice that a character uses the same mannerism as her mother; that a soldier’s name refers to a famous (or failed) battle in the past; that a church is described in a way that repeatedly associates it with sacrifice, or safety, or (alternatively) corruption. When you do just “react” and reflect–which is a good thing–the idea of close reading is that you’ll be able to come up with a deeper, or more informed response, even if you ultimately disagree with the ideas or feelings you find. (I often warn students that it’s deadly to disagree with something a writer is not saying.)

That’s Why the First Answer is–Yes! Please do!

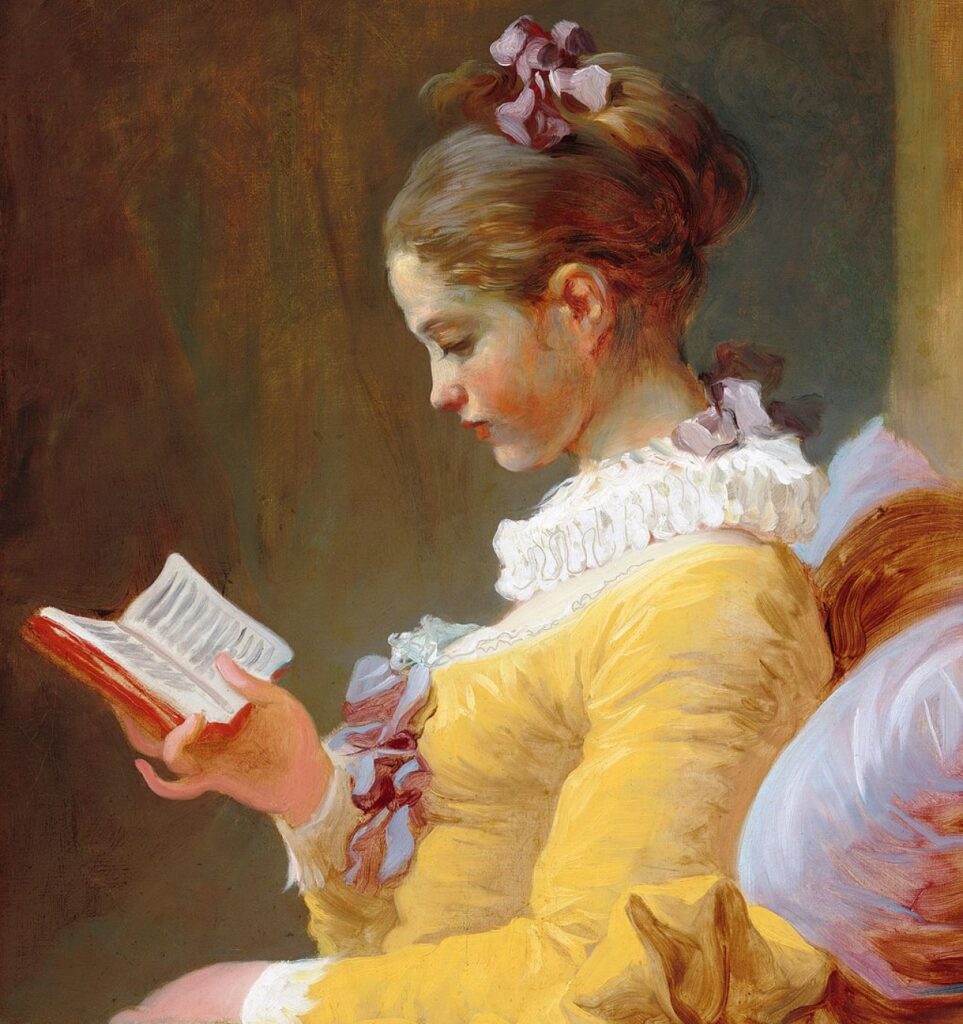

And so, of course: read closely!!–in both the general and the technical sense. It’s especially important to understand the meanings of “analysis” above–breaking a story down into parts, and thinking from the writer’s point of view. And, yes, focusing on a passage is very useful when analyzing narrative journalism, because it’s a bit like zooming in on the paint strokes or use of light in a painting. You’re not just looking at the subject matter (or “news content”)–you’re looking at how it is molded into a story. I’m often saying: forget that it’s nonfiction or journalism for a while–and just read the work as if if were a short story or a novella or a longer work of fiction–you’ll get much more out of it, if you do.

Take, for instance, titles. New Yorker staff writer William Finnegan titles his book about America’s disadvantaged youth Cold New World for many literary reasons. For one, his title is an allusion to Shakespeare’s The Tempest, itself set in the “new world” (the Americas), and featuring a debate between the main character Prospero (exiled from Europe) and his daughter Miranda. When she sets her eyes on what she thinks are inhabitants of that new world for the first time, she says “Oh, wonder! / How many goodly creatures are there here! / How beauteous mankind is! O brave new world, / That has such people in ‘t!” But then her more experienced father says “‘Tis new to thee,” meaning he himself recognizes the all-too-familiar presence of the “old” world’s (Europe’s) corruption. This allusion signals that Finnegan, who has lived abroad and reported on wars in Africa, also sees many similarities between America’s scenes of poverty and violence and what he saw in Africa and elsewhere. Cold New World also alerts us to the idea that Finnegan’s subject is the post “Cold War” landscape of the U.S.

Many book titles or chapter titles, many characters’s names and description, many place names in narrative journalism call up this kind of literary richness, and many journalists are using the “story forms” we can find in novels or epic poems or tragic plays to expand on those meanings.

That, in large part, is what Chapters 3-through-5 are about: learning about “story-forms” and different literary designs that journalists use. (I’ve also provided suggestions about how to write a paper on a work of narrative journalism.)

But There’s a Catch, too–Isn’t There?

Yes: more than one, actually. Let’s start with names. As I’m sure you realize, in a work of fiction, writers can invent the names of all of their characters–and thus they can embed allusions, historical references, and poetic resonance in any of them. But in journalism, the names refer to the names of actual people (who probably have gotten them from their parents!). So a journalist is necessarily restricted in what can be done–and this applies, of course, to a wide variety of elements (maybe just about all of them) in the story. In fact, if you think about it, these people aren’t actually “characters” except in a very limited sense: they have their own agency, they say what they want to say, go where they want to go. The journalist isn’t free to change any of that, except in rare circumstances where it’s necessary to disguise the person’s name or the location, etc. where something happened. (If you don’t want, say, a government agency to find them). Some small changes are sometimes made to “cover one’s tracks,” or to simplify a story-line–but that’s rare. (See the videos by journalists listed on this website, to see how some famous one finesse these matters.)

The Problem of “Omniscience.“

If you start with the premise above–that journalists can’t invent–well, other “literary” effects also can fall by the wayside. For instance, you’ve probably been taught at some time the idea of a writer’s “omniscient” point of view–the kind where the writer or narrator seems “god-like,” since that narrator can see into characters’ minds, go anywhere in the world of the book–even move back and forth in time.

Well, in journalism: there’s no such thing as “omniscience.” Sure, a journalist can make it look like they were “omniscient” or present where they were not–that’s part of the artistry of writing. But the line is pretty clear. The critic and scholar David Shields has put this problem well. If you’re reading a Henry James novel, and it says such-and-such a character “thought” something…well, that’s what they thought. Henry James says so, and in his novel, he’s god. But when a journalist does that, what they usually mean is “that character told me that’s what he thought.” In other words, it’s an implied form of attribution, really.

. . . Which is Why Selection is Key

But don’t despair. In fact, close reading in the technical sense applies because of the authorial privilege of selection. That is, writers do indeed create imagery and motifs, tricks of point of view, offer allusions–the whole gamut of literary devices, resources in language and word choice, “back stories” from history and culture that writers have to work with. They can do so because–say, out of dozens of scenes or lines of dialogue or details that were in front of the writer–journalists create narratives by choosing particular details and scenes to emphasize. And along with doing so, they still have at their disposal a huge array of techniques that can be quite “novelistic” in effect–and styles that range from the epic, to the “realistic,” to the postmodern. As the subsequent Chapters on this site hope to show.