A Reporter Looking to Get the Story

Shots ring out in an alley on a cold winter night, and a body falls on a city pavement. Someone thinks to call the police, and in due time they indeed roll up in black & white patrol cars. They push a few early onlookers back, bend over the body, and then begin to roll out the yellow “CRIME SCENE: DO NOT CROSS” tape. They do so because, as the great American journalist Stephen Crane loved to say, albeit with a wink: “a crowd gathers.” And imagine, if you will, in and through that gathering crowd walks a stubby, trench-coated man in a floppy hat, smoking a cigar, carrying a big box camera with an enormous flash that rattles the night. He’s elbowing his way to the front, crouching down, capturing the glint of his own flashbulb off the graininess of the pavement: snap, flash—the illumination races down and over the body, filling the alley for a split second. In the flash, you glimpse a steel-black revolver lying inches from a lifeless hand.

The photographer returns to his 30s-style Chevrolet sedan parked illegally, on the other side of the street. From the photographer’s chatter with the cops, you realize that he’s intercepted their radio calls at his own apartment—a greasy grim place that you later hear that he has wired to connect to the police dispatcher. He will, in fact, produce one of most famous “crime scene” photographs of this kind–an image sometimes known as “Hell’s Kitchen.” And yet, through it all, the odd man is also cursing under his breath. You see, he’s angry that he arrived too late again. In fact, he didn’t want just another “crime scene” photograph. He wanted to be there as the bullet arrived, before the body had fallen.

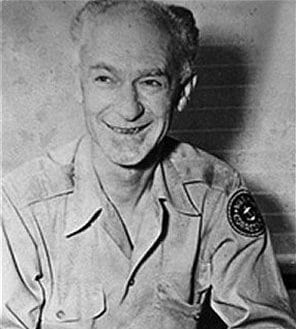

The odd man of this scene I’ve just described—a character who later became the centerpiece of an X-files episode, and had an exhibition at the Getty Museum in Los Angeles devoted to his work–is, of course, “Weegee” (Arthur Fellig), the famous tabloid news photographer from the 1930s and 1940s. Fellig gave himself the

name “Weegee” to remind others of a “Ouija” board, and thus to speak to the desire I’ve mentioned above: the hope that, someday, he could be present not to the aftermath of a crime, but to the moment the crime originally happened. He dubbed this fantasy “psychic photography.”1

“The Story” as Reporters Will Usually Define It

As odd as it may seem, however, in fact Weegee’s dream is only an exaggerated vision of the desire often at the heart of modern journalism: to get “the story,” the catchphrase reporters use. Indeed, in many ways, photography itself came of age alongside modern journalism’s quest for public legitimacy. The authority of a news photograph, that is, lies in what we call testimonial authority. Documentary photographer Jacob Riis (whom I will discuss in Chapter 4) even identified the flash of flash photography with evangelical illumination and truth itself—a light brought into the darkness of poverty or crime. Indeed, it’s often said that a photographer seems to make the photographer, or the reporter, disappear: it’s as if we become the witness.

Young reporters are often told by their boss to “get the story,” and whether they do or not can often decide whether they keep their job. And by “the story,” journalists habitually refer to the element in an event that has the most news value, the element I have been calling the “news content.” Reporters talk about having a nose for news; in the 19th century, U.S. foreign correspondents were in fact sometimes called “news hunters” or “news gatherers,” as if a story was something to be tracked down like a lion. Here are some different images of American war correspondents over the decades that capture the identification of the reporter’s craft with exploration, adventure, or performing something like a soldier’s duty:

Sonia Tomara, New York Herald Tribune

Rosette Hargrove, Newspaper Enterprise Association

Betty Knox, London Evening Standard

Iris Carpenter, Boston Globe

Erika Mann, Liberty magazine.Source: US National Archives Public Domain

The word “Story,” however, has Other Dimensions

But for starters, we should notice that the word “story” doesn’t have that single meaning. For example, a family member or a teacher may read us “stories” in the sense of fairy tales, adventures, or fables. In this second sense, that is, a story is a narrative–as I said in Chapter 1, a collection of episodes put into a particular sequence, and seen from a particular point of view.

So there’s an important tension: journalists themselves usually speak of “the story” not as the narrative form into which their reporting will be inserted, but to the set of facts, testimony, and witnessed events prior to the choice of narrative form. In other words, reporters talk about going out and “getting the story,” because—or so it seems–they believe it exists in events, not in the means by which such events might be told. When cultural studies scholars and media critics refer to mainstream journalism’s assumptions as “positivist” or “empiricist ” norms, this is usually what they mean: that a reporter feels a story is something “out there” that they can gather up.

Meanwhile, there is a third dimension of “the story” that also gets into the mix. This is suggested by the colloquial way Americans use the word “story,” for example, when they meet someone for the first time: they say “so, what’s your story?” Or, if we’re confused about the way someone is reacting, Americans will quizzically say, “what’s their story?” In other words, Americans use the term “story” to refer to someone’s background or life history, or more commonly to something like “where did you come into these events?—how are you connected to them?” and “how would you tell it?”

Now, it might seem that this third meaning has very little to do with our first two meanings. But in fact, a good reporter is always asking people to tell their story—to tell the journalist who they are, or what their version of events is. In journalistic circles, this is referred to as the “subject’s” story, with again the “subject” being the person (or persons) directly involved in what will be reported. Even though journalists want to be direct witnesses, they more often arrive, like Weegee, after the bodies have fallen.

However, there is yet another, final sense of “story” that is connected to what we normally call “legwork.” Sure, we can reconstruct on our own how writers have conducted their research; sometimes we have to do that, because a reporter writes in a way that deemphasizes their own role or even seem “invisible” to us as readers. But in many other cases, works of narrative journalism often feature the journalist as a “character”–and even when they don’t, they often implicitly suggest how the journalist researched and reported their narrative. For example, they tell us about riding on helicopter, or say “when I met the General in Baghdad two years later,” and so on. Even when they’re not depicted in the narrative, we understand that they’ve often formed very close relationships with the subjects (the people) they’re reporting on.

Now, I’ll admit, this last point can seem like pretty minor stuff. But whether we like it or not, many of the finest works of narrative journalism read very much like a memoir. Sections of Michael Herr’s Dispatches, for example, originally appeared in Rolling Stone and Esquire magazine. However, the book version is looking back on what it was like to be a reporter in that war: it tells us about what it felt like to ride a helicopter in Vietnam, the temptations and risks to be a voyeur, and about the “personal movie” about heroism and masculinity that Herr confesses was in his own head at the time. (And after that time.) And so, by reading Dispatches, we learn something about how Herr collected stories, where he traveled, which events he witnessed, even—as various critics have said—about how his own memory worked.

Likewise, whenever a reporter writes in the first person, we’re getting an account of how they tracked through the story that we are reading. Barbara Ehrenreich, as I will discuss below, gives us a first-person recounting of her journey as a reporter in Nickel and Dimed: On (not) Getting By in America (2001), about why she made her decision to start in Florida, to adopt an undercover identity, and seek out employment as a low-wage waitress and hotel domestic worker. In other words, as she writes her story of low-wage work, she also recounts her reporting strategy and experience—the two are actually tied to each other in the book that we read.

As I’ve said in Chapter 1, one way to think about this is to imagine the literal footprints a reporter leaves in the text. It also sometimes helps to think of a perimeter or horizon line around your reporter. In real time, a reporter can’t be everywhere. So, what were the possible limits on how far they could see?—and what might have fallen outside of that horizon line? How is that horizon recreated in the narrative itself?–or is it transcended, somehow?

As we’ll see, there are many other questions one might ask about this fourth dimension of the “story:”

- what kinds of research, direct witnessing, or legwork contributed to the narrative?

- where does the reporter say they went?

- Who was interviewed? What was the pattern or routine of information-gathering established by the reporter?

- How, and how fully, did the reporter immerse themselves in the scene, or the group of people within the story?

- Did a reporter show us their tracks, or cover them, in the final written product?

- What kinds of emotions is the journalist sharing with us, now? How much of the journalist in the text seems like a persona, a kind of mask worn at the time—or even created for what we’re reading?