Effects of Style and Selection in Narrative Journalism

Guiding Questions for This Chapter

What makes a work of reportage seem “realistic?” –why do we find ourselves feeling as if we’re experiencing events just as the reporter did, or that the people in the story did? How much of our reaction is a result of effects of style? What are those effects, and how can we respond to them with a more critical eye?

I am a child of the Atomic Age. I was born just a few years after the United States dropped two atomic bombs on Japan, one on Hiroshima and another on Nagasaki, in August of 1945. Defining the opening blow in what became called the Cold War—a label initiated by an often-forgotten essay by George Orwell— these bombings even shaped the politics and culture of my own suburban boyhood. In elementary school, for instance, I was introduced to civil defense drills, while a neighbor across the street in my otherwise bucolic world dug a bomb shelter in his back yard. I became an avid watcher of the atomic-radiation science fiction movies on TV—and, probably as a result, had many nightmares about waking up and finding that my world incinerated. And much later in life, I discovered something else I should have known about the Atomic Age: that my father, who had served in the Navy in World War II, had been waiting in the Pacific fleet off the shore of Japan while President Harry Truman made up his mind about dropping those bombs. Given that part of Truman’s calculation was about saving American lives—well, I guess you get the point. There is a possibility that I am alive because of the Bomb.

Imagine my interest, then, upon first reading John Hersey’s classic work of reportage, Hiroshima (1946), in my late ‘teens. (I didn’t know then that Hersey’s account had been given the space of an entire issue of The New Yorker when it appeared in 1946.) Hersey’s report, as you probably know, centered on the experience of six residents of Japan (one of them a visiting German Jesuit, the rest Japanese citizens) in the moments and days following the first bombing. Carefully describing the blinding yet oddly noiseless flash of light that signaled the bomb’s destruction across the city of Hiroshima, controlling his narration so that it might recreate the initial confusion of these Japanese residents on the ground, Hersey seemed to capture the attempts of these everyday citizens to survive and, in time, mentally process the meaning of the Bomb’s arrival. And I remembered exactly how I responded, at first, in reading Hersey’s book—a response that many of us have to a powerful work of reportage. I felt that Hiroshima seemed more than simply vivid: I thought it was extraordinarily “realistic.”

Recognizing “Realism” as a Style

Now, that’s a common reaction, and yet it’s an important one to understand properly, too. When we have a reaction like that, I think we’re trying to say something more than what has been reported to us seems to have really happened. Rather, we’re probably talking about how a book’s style makes us feel as if the event happened the way it is being described. The reading experience, that is, makes us feel almost as if we were immediately present to the event, or at least to feel that we know what it was like to have actually been there. As a result, the style of a work of reportage can seem to contribute significantly to the authority that we grant it. If a given work seems more realistic, in other words, it can also seem more accurate, truthful, or authoritative.

To be sure, probably the most frequent reason we turn to a work of reportage is to bring us closer to events that have previously been outside our experience; if the work seems realistic, we think, so much the better. That’s very much part of the empiricist claim I discussed in Chapter 2. But again, this “empiricist” claim is usually something you have to “break through,” and understanding realism is a big step in the right direction. In effect, “realism” often makes it seem as if 3 of the 4 dimensions we’ve discussed are simply equivalent: that the story the report tells is the same thing as what “actually” happened, and that it’s the same thing any human subject in the story would tell, too. As I pointed out in Chapter 2–well, it just ain’t so.

Just take my own first reactions to Hiroshima. To call Hersey’s book realistic, as I did, was a bit naive, perhaps even contradictory. Rather, precisely because the Bomb was an entirely new event in human history, I really had no way of knowing, myself, what it was like to experience it. Assuming, that is, it could be said to generate a coherent experience in the first place, or be “like” something more familiar to me. The very point was that the Bomb was not familiar at all, and in fact it generated many different kinds of experiences. Moreover, a report that is, say, actually based in direct witnessing could be written up in a way that might not seem realistic to us at all: take, for instance, Hunter Thompson’s famous Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (1971). (I’ll be talking about some of these kinds of “un-realistic” texts in Chapter 5.) But that’s precisely why it’s helpful to think of stylistic effects in realistic works of reportage as a kind of spell cast over us: we are so caught up in the story that we don’t pay attention to what it’s doing to us. Such a spell, in fact, often makes us forget that every work of reportage is, by definition, also an interpretation of the events being reported on.

And so, here’s the challenge. Along with absorbing the three other dimensions of “getting the story” I discussed in Chapter 2—the news-content story, the story told by specific persons inside the event, the story of how the narrative was constructed in the first place–we also need to pay attention to the literary effects of the story-form, to effects of style and selection which are what have been called reality effects. Essentially this concept, famously associated with the French theorist Roland Barthes, says that even seemingly insignificant details of a text—for example, descriptions of objects or the setting, or an author’s renderings of the way people ramble when they talk—actually play a substantial role in creating the illusion that we are in the presence of reality itself. This is one of the biggest challenges to our experience of reading many classic realistic works of narrative journalism: coming to terms with the fact that “reality effects” can have this impact on us without our fully being aware of them.1

Chew for a minute on this paradox from a literary scholar named Andrew Corey Yerkes, writing about the American novelist Sinclair Lewis:

Modern realism allows the reader to suspend disbelief and forget the conventionality of the text, as though looking through a window into a world that is recognizably real in terms of physics, human motive, and social behavior.2[2]

In other words, realism is a style that–well, makes us forget it’s a style. As Yerkes says, it makes us think we’re looking through a window, not a lens. We often think we can separate the art of reportage from its contents. But not for long. Instead, we have to remember that what we’re looking at is, after all, writing, not the event itself.

What Do We Mean by “Realism”?

“Reality,” “realism,” “realistic”–these are, of course, very slippery words. Even in everyday speech, English-speaking Americans tend use words connected to reality or “the real” as words of praise. One says someone is realistic not just if they are truthful, but if one thinks they demonstrate a level-headed view of events. Or maybe we tell someone to “get real” if we want them to dispense with the illusions we think they’re holding. To many reporters, being realistic means having the requisite skeptical temperament around the events they report on–to put a premium on being dispassionate, accurate, fair-minded but dubious of unsupported claims. Reporters often want to show us that they are not deceived by the grand claims of just anyone. Instead, they typically test such claims against documents, scientific findings, or the accounts of people more in the know—or against their own witnessing.

This is especially true when the reporter uses the first person “I.” Here, as with Nickel and Dimed, the journalist retraces their footsteps, in order to establish the authority of the report: we see how it was produced. In the direct-witnessing tradition, the choice of a first-person narrator works to show us how facts were gathered. In other instances, long-form journalists turn over the business of story-telling to their subjects. This is what is sometimes called testimonial journalism. The subject is being given more power to tell their story while the journalist seems to disappear from the text. Testimonial journalism is still witnessing–it’s just presented in a different story-form that “cedes” the telling to the subject.

In testimonial journalism, the word “witness” sometimes takes on the older meaning of “bearing witness”: events are being “testified to”–as, for instance, in Ida B. Wells’s Red Record (1895), a powerful indictment of the horrors of lynching. The journalist-witness shares the subject’s suffering or past experience. But even this approach can take many different forms: personal memoir, a traveler’s account, or a letter from abroad. (The older meaning of correspondent, in fact, was a letter-writer: a person who wrote back to audiences in the U.S.). Or, perhaps such a story begins by describing a journey: the reporter’s arrival into a place or social setting that simply seems foreign but is actually quite personal to the reporter. (For example, Nick Reding’s Methland [2009], about the methamphetamine crisis ravaging the Midwest.) As in travelers’ stories or anthropological accounts, the reporter is represented as disoriented at first, but then typically “breaks through” to the inside of the story. We realize, then, that we’re reading an initiation story, and as readers we often share in the emotions and the shocks of the reporter’s journey getting past social or cultural barriers. (A very good example of this is the opening sequence of Geraldine Brooks’s Nine Parts of Desire [1994], which tells us a woman from the West reporting on the Middle East sometimes isn’t allowed to interview anyone.) Reporters also typically end their stories by recounting the culture shock of returning to the world they originally came from–often the “home” of the reader as well. These are the many ways reporters help us identify with a story, and make us feel it’s realistic. Indeed, some scholars of narrative journalism use the term ethnographic realism to describe this last style of narrative journalism. You can find the pattern I have described here—a voyage out and back, from home to another environment and back–in memoirs of war correspondents, reporters who go undercover, and so on.

But why might such styles strike us as realistic? Perhaps we’re caught up in the excitement of the story; all of us have had the experience of starting out as an outsider and then breaking through. Moreover, this form of witnessing is liable to persuade us because memoirs—from Stephen Crane’s famous “War Memories” (1899), to Ernie Pyle’s books about World War II, to Dexter Filkins’s report on Afghanistan and Iraq, The Forever War (2008)–are often re-composed out of dispatches written in the moment itself. Journalism’s “first draft of History” creates that feeling of immediacy. In some of the most well-known stories of a reporter’s immersion or undercover work—Nellie Bly’s exposé of the Blackwell Island insane asylum, Ten Days in a Mad-House (1887); George Orwell’s recounting of being Down and Out in Paris and London (1933); Ehrenreich’s Nickel and Dimed (2001); or Ted Conover’s work as a prison guard in Newjack (2000)–the reporter may start out as an innocent whose education in experience we follow. Over time, being immersed seems to mean becoming intimately connected to the world being reported on.

So-called journalistic immersion narrative, such as Nickel and Dimed, can be a powerful approach. And as I said earlier in this Chapter, quite often we think the witnessing and the journey are what make an immersion story seem authentic and visceral. But in fact the style of these accounts goes a long way towards making it feel real, too: the descriptive intensity, the confessional voice, and the sensation of shock work together to make us feel that we are sharing in the sensory experience of the reporter. (If it helps to call the reporter an “avatar,” that’s fine in this case; I prefer persona). By the power of words on the page, our bodies can seemed wired into the journalist’s own. Take a look at these passages below:

All the windows in the hall were open and the cold air began to tell on my Southern blood. It grew so cold indeed as to be almost unbearable, and I complained of it to Miss Scott and Miss Ball. But they answered curtly that as I was in a charity place I could not expect much else. All the other women were suffering from the cold, and the nurses themselves had to wear heavy garments to keep themselves warm. I asked if I could go to bed. They said “No!” At last Miss Scott got an old gray shawl, and shaking some of the moths out of it, told me to put it on. . . . So I put the moth-eaten shawl, with all its musty smell, around me, and sat down on a wicker chair, wondering what would come next, whether I should freeze to death or survive.

(From Nellie Bly, Ten Days in a Mad-House)

…my customers are hardworking locals . . . and I want them to have the closest to a “fine dining” experience that the grubby circumstances will allow. No “you guys” for me; everyone over twelve is “sir” or “ma’am.” I ply them with iced tea and coffee refills; I returned, midmeal, to inquire how everything is; I doll up their salads with chopped raw mushrooms, summer squash slices, or whatever bits of produce I can find that have survived their sojourn in the cold storage room mold-free (18-19)

(Barbara Ehrenreich in Nickel and Dimed)

[The prisoner] walked right up to me, stood less than a foot from my face, and radiating fury, said, “You’re going to learn, CO, that some things they taught you in the Academy can get you killed.” . . . I hadn’t heard those words spoken to me before, and that, in combination with the man’s standing so close, set my heart racing. I tried staring back at him as hard as he was staring at me, and didn’t move until he had stepped back first. (99)

(Ted Conover in Newjack)

It’s hard not to feel we are “in the scene” with these talented reporters. They’re calling up all the senses: smell, taste, the temperature of the room and more; it’s easy as well to feel threatened in the way that they were, or shocked–and so on.

However, it’s time to widen our perspective a bit, and maybe tighten our terminology. That is, it’s going to be more helpful if we start to use the terms realism or realistic to describe the effects of certain styles–certain literary techniques, for now–rather than simply the “what” of what is being reported or the reporter’s reactions to it. Not just the story-line alone, but the style in which it is cast. For me, that meant thinking harder about how Hersey’s Hiroshima was written.

Learning from Realistic Paintings and Drawings

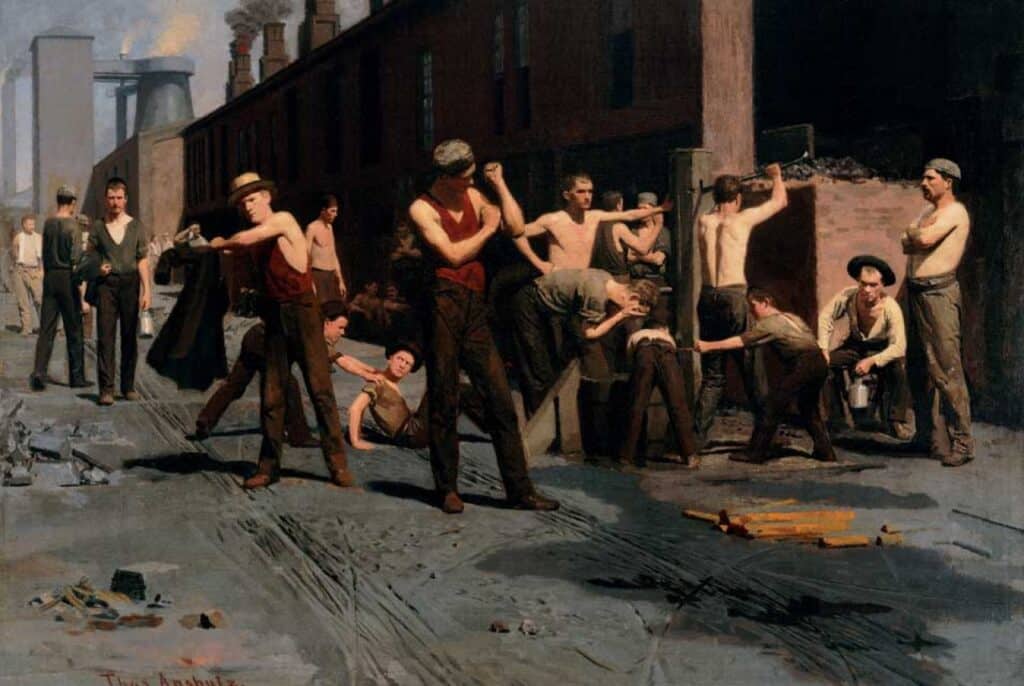

One of the better ways to understand the reality effect of style is to look at how it is created by a “realistic” painting or drawing. Look at the paintings in the gallery below—all of which, though they come from different artists and countries, are typically categorized as examples of artistic Realism:

So why do we call these paintings realistic? Well, it is true—part of it has to do with content: these painters are interested in everyday life: work, leisure activities, known landscapes or locations, and so on. But more precisely, we call them realistic because they all recreate the illusion that we we are actually present to those real things, ourselves—as if we were right in the room, or on the scene, or again looking through a window.

However, of course we’re not present to these scenes at all. We’re looking at a flat canvas with a bunch of paint or lines on it. The painter has tricked our eyes and our mind. Typically, paintings like these

- make objects look like they have dimensionality or weight or substance—that is, bodies in the paintings can seem fully rounded, or mist can feel wet, or the velvet of a hat can be made to seem smooth. By a figure’s posture, a muscle can be made to seem sore, or cloth can seem bunched up, or feet can seem as they are flat on the ground;

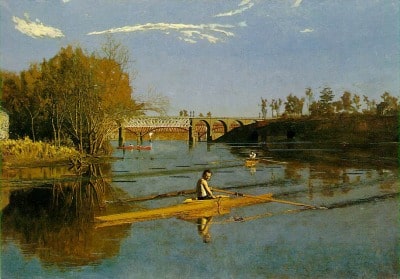

- make us feel we are observing from a location that isn’t an actual place where we could be standing—rather, we might be floating in the air. (In the Eakins painting of the rowing scull on the Schuylkill River, we’d actually having to be standing on the surface of the water).

So how are these illusions created?

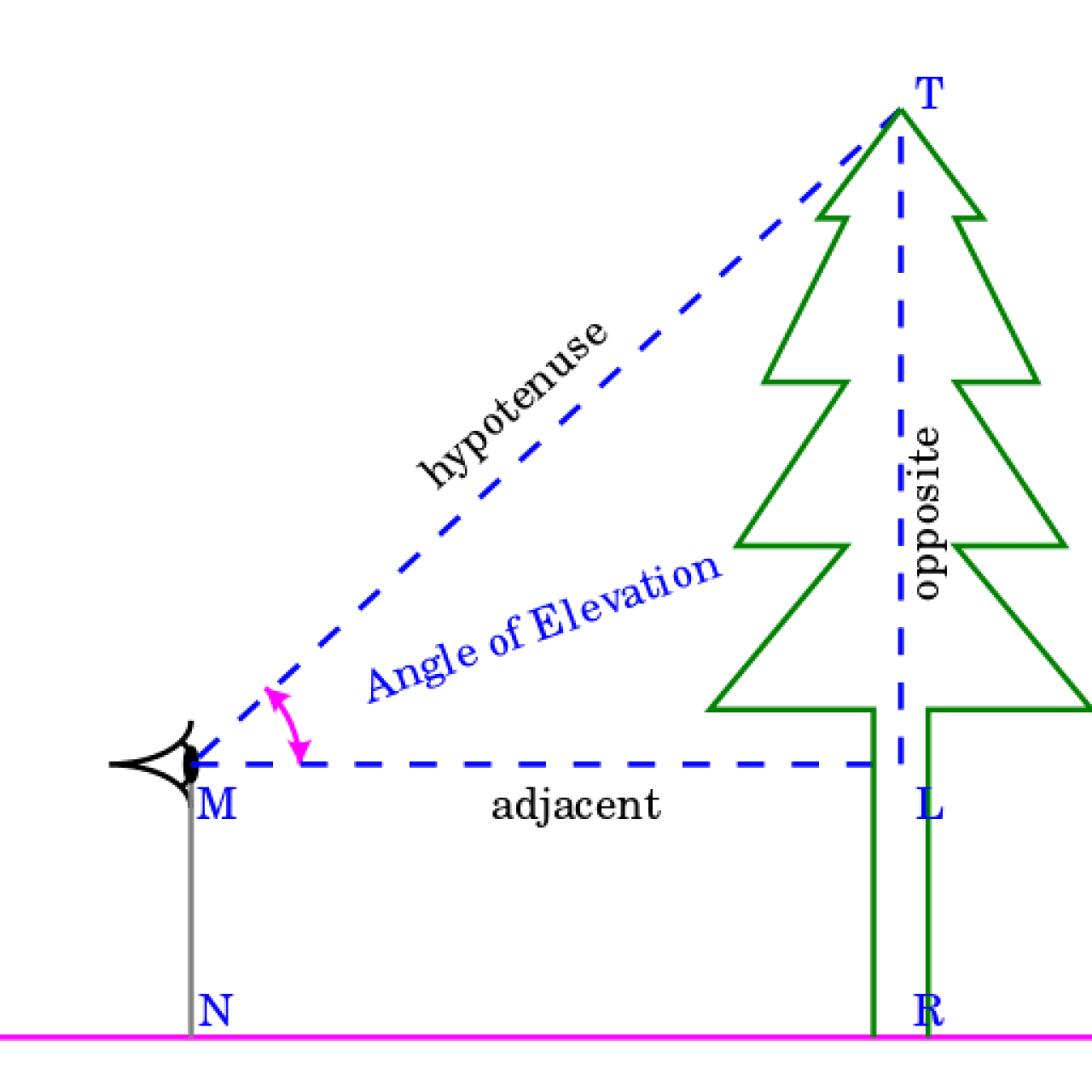

Well, in part, this is a result of a long tradition of realistic conventions in painting handed down since the Renaissance. In the fifteenth century, artists began to figure out how to paintings could be designed to trick how the eye sees, and to translate what is our three-dimensional world onto the flat, two-dimensional surface of a canvas. The main solution they came up with was what we now call linear perspective. The surface of the painting was broken into sections or zones, often starting with a ground level on which objects or persons could be placed. Then, it was a matter extending that visual ground up to the level of what we now call a horizon line which was narrower than the ground line. The height of that horizon line on a painting, painters like Leon Battista Alberti realized, was directly related to the hypothetical height of the viewing point (our eye) looking into the painting’s recreated scene:

The next two steps followed directly: our mind thinks objects that are larger are closer to us, while objects that are smaller appear to be further away. Moreover, things sharper in focus, or more detailed, seem to be closer, while things that lose that detail seem further away from us. Thus, people who were actually the same height could be drawn smaller and shorter and less distinct if they appeared in the background of the painting. But you’ll also notice a related trick of the eye: while such figures in the background are drawn to be shorter, they are usually also elevated, raised up on the screen/canvas—and that’s because artists realized that the position of objects on a canvas could be calculated depending on how those parallel lines of height converged on a chosen vanishing point on the horizon line—as you can see in the example of the comparison I’ve provided below.

When we say some forms of realism have a classical structure—in the visual arts, and in writing—this is partly what we mean: that such forms are built around this system of perspective, this illusion of space and fullness.

And what about that feeling in, say, the Eakins painting above, where it seems we’re standing on water? In the Eakins painting, the viewer is sometimes said to be placed in an Archimedean position, so named after the Greek mathematician Archimedes, who hypothesized he could move the earth with a lever if he could be given another place to stand on. (In other words, the viewer of those paintings often stands on a space that doesn’t really exist, as if outside the world being looking at. In writing, a comparable effect would be the “fly on the wall” narration. In that form of point of view, we feel we are looking in but not really standing anywhere in the story itself.)

But What Do “Perspective” or “Depth” Mean for Writing?

But what would be equivalent of the above in writing, and specifically in long-form journalistic writing? Well, as in painting, realism in writing controls the density of detail. For instance, because some characters are given more coverage in a storyline, denser descriptions, or more chances to speak, this has the effect of making them seem more dimensional or, as we commonly say, more “rounded.” We probably also feel closer to them emotionally (though the emotion can be of any kind). Conversely, characters that don’t get those things are said to be “minor,” or “flat,” or less fully “fleshed out.” All of these effects were visible in the immersion samples I quoted above.

Likewise, point of view—a term we use for the kind of narrator used in a literary text—has a similar kind of visual dimension (indeed, notice the phrase: it literally speaks of the position from which things are seen). But this can of course be handled differently: for the immersion writers above, it’s the “I” that draws us in–we’re in that person’s shoes. But conversely, if a narrator is not given a name or identity in what we read, and doesn’t participate in the action—points of view we call “omniscient” or third person, typically—that too can be powerful in a different way. For instance, it can have the effect of making the journalist seem invisible, even “Archimedean.” Indeed, if the narrator is able to move back and forth in time, see into characters’ minds, and so on—that kind of “omniscience” really does seem God-like, in the colloquial sense of being invisible and yet all-powerful. (See, in turn, what I say about journalists’ use of hindsight below).

You might also think of setting–and the amount of detail–as creating the feeling that we are looking at a complete and even whole world-unto-itself. (Victorian novels, for example, usually have a sprawling cast; upstairs and downstairs intrigue; rich and poor; master and servant; men and women. It can seem as if it’s a complete world re-created for us.) Put all those effects together—and you often have an overall illusion that many readers will say “reads like a novel.” (Some think this form of realism has become the default setting for narrative journalism, too.) In turn, this seemingly styleless style reinforces some journalists’ claim to be impartial or non-judgmental, or that they’ve had little effect on what they have observed. In short, it can reinforce an illusion of “objectivity.”

Reading Like a Novel

But sometimes, as well, this phrase–“reading like a novel”–can have a much more precise and fuller meaning. The “default” setting I mention above actually has a long history–a way of telling a story that came of age in Europe and the U.S. in the 18th and 19th centuries, the design we now call a novel. (Even though there are many different varieties). But this aspect of “reading like a novel” has more to do with how stories are built–as it were, not the “interior decoration” of voice and descriptive detail but their internal architecture or design.

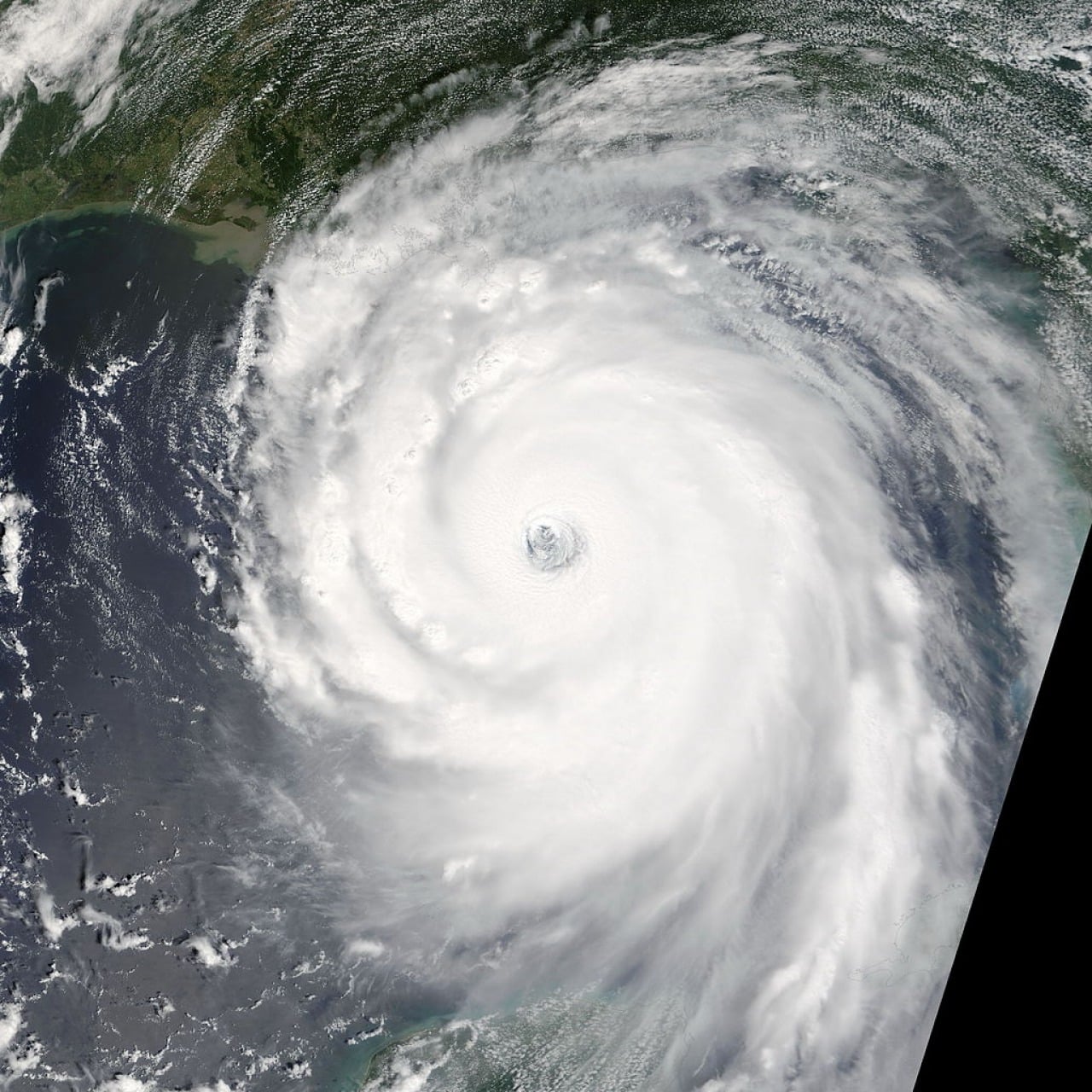

What do I mean by that? Well, in what scholars commonly call the realist tradition, writers began to use a form of the novel featuring a largely linear plot with a protagonist who experiences growth or a personal crisis of some kind. Often, the novel had a central protagonist whose name became the title of the book: Huckleberry Finn, Silas Marner, and so on. The story of that character was a little like the spine of the book’s skeleton–with other characters, and other plots, connecting into it. Dave Eggers’s Zeitoun (2009) is a good example of a contemporary work of narrative journalism using this model: here, one character and his family become the main lens through which we re-experience Hurricane Katrina.

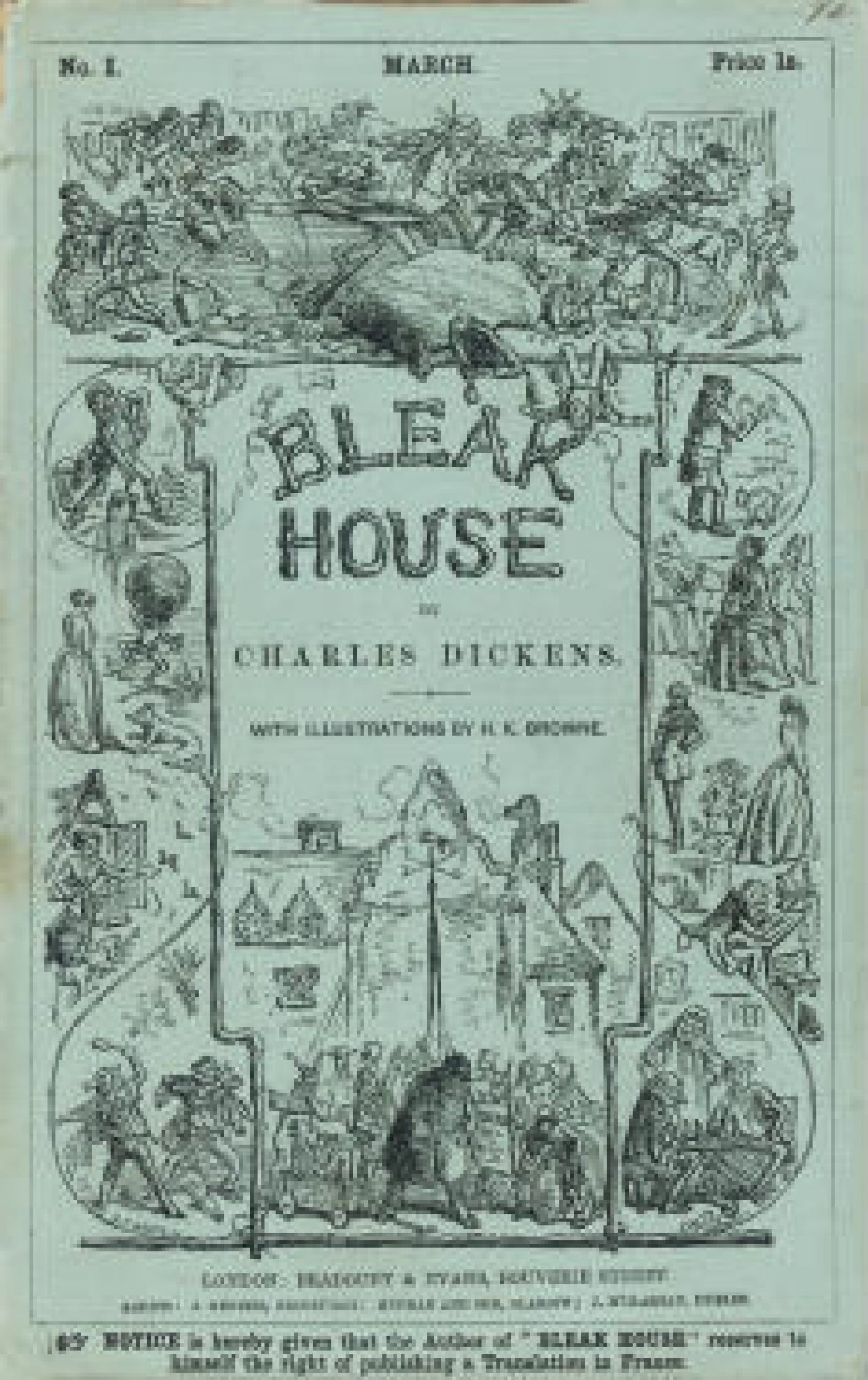

These days, when people say that a work of narrative journalism reads like a novel, they usually mean variations on that basic model–perhaps with a family at the center, or a more ambitious cast. (Alex Kotlowitz’s story of gang violence and boyhood in Chicago, There Are No Children Here [1991], is another good example of a journalist adapting this style—more on this text in following.) Charles Dickens’s Bleak House (1853)–much more panoramic in the sense of having a big, ensemble cast and a bunch of plots and subplots helping to survey a wide swath of society–was one model for Nina Bernstein’s book about contemporary foster care, The Lost Children of Wilder (2001). Adrian Nicole LeBlanc’s Random Family (2003) reads like a novel of this kind.

Naturally, this form too can be modified. Perhaps it will reappear in a collective biography like David Finkel’s The Good Soldiers (2009) or his Thank You For Your Service (2013); or a narrative that traces different common persons across great historical transformations, like Jason DeParle’s American Dream: Three Women, Ten Kids, and a Nation’s Drive to End Welfare (2004), or Isabel Wilkerson’s story of the Great Migration, The Warmth of Other Suns (2010). Not uncommonly, this last variation also shares a lineage with the “epic” tradition of poetry.

In general, however, to make a work of narrative journalism read like a novel, reporters commonly turn to three stylistic reality-effects. Here they are:

Reality Effect #1: Choosing a Style of Attribution

If you’re a reporter filing a daily news story, you lean quickly that all facts–and especially quotations–have to be subject to what the profession calls attribution . This is the technique by which facts or statements are rendered as “according to” a particular person, institution, or source of authority. (As in “According to the Pentagon…” or “as the Department of Defense stated,”…and so on.) One of the most revered forms of verification in all of American journalism, attribution generally has to be “adjacent” to such facts or statements–in the same sentence or paragraph. If it’s not directly identifying a person or source, protocols for other kinds of statements–background, “deep background,” on condition…all come into play.

And yet, if you turn to works of narrative journalism–especially in book form–you’ve probably notice that these rules have been, to put it mildly, relaxed. That’s because one of the first effects of “reading like a novel” is a “smoothing out” of the narrative so that it’s not clogged up by endless “according to’s” and so forth. We start to grant the long-form journalist much more scope and authority as a result: we assume such things are “as told to” or directly seen by the reporter, usually. And by doing that, often the “immersive” effect is enhanced: we “suspend disbelief” and go with the reporter’s novel-like account. Sounds like a plan.

But really, there’s much more to it than that. To illustrate some of the many effects involved in removing attribution, in what follows I’ve copied down two passages from Hersey’s Hiroshima, which is famous for this erasure of attributions. Hersey uses, as you’ll see below, a dispassionate, third person style that can make us feel we’re watching actual events. But what I’ve decided to do is show you what the same passage might look like with a series of hypothetical attributions put back in, in bold print below. I’ll try to suggest, through my inventions—including converting Hersey’s third person to direct quotation–how Hersey might have chosen to give us more explicit sources for his facts, his telling occasions, and so on—but in fact chose not to. What follows are two descriptions of one of Hiroshima’s main characters right before the blast hits him:

Mr. Tanimoto was a small man, quick to talk, laugh, and cry. He wore his black hair parted in the middle and rather long: the prominence of the frontal bones just above his eyebrows and the smallness of his moustache, mouth, and chin gave him a strange, old-young look, boyish and yet wise. He moved nervously and fast, but with a restraint which suggested that he was a cautious, thoughtful man. (3)

Before six o’clock that morning, Mr. Tanimoto started for Mr. Matsuo’s house. There he found that their burden was to carry a tansu, a large Japanese cabinet, full of clothing and household goods. The two men set out. The morning was perfectly clear and so warm that the day promised to be uncomfortable. A few minutes after they started, the air-raid siren went off—a minute-long blast that warned of approaching planes but indicated to the people of Hiroshima only a slight degree of danger, since it sounded every morning at this time, when an American weather plane came over. (4)

Here’s the same sequence, but now I’m putting some possible attributions back in. (I should emphasize again that I’m just making these up—I don’t mean to suggest I’m inferring them from the original, or from Hersey’s remarks, or anything like that):

Mr. Tanimoto was a small man, quick to talk, laugh, and cry, his friends all said. As photographs from the time showed, he typically wore his black hair parted in the middle and rather long: the prominence of the frontal bones just above his eyebrows and the smallness of his moustache, mouth, and chin gave him a strange, old-young look, boyish and yet wise. Even when I met him two years later, he moved nervously and fast, but with a restraint which, as he later said to me, was intended to suggest that he was a “cautious” thoughtful person. (3)

Before six o’clock that morning, Mr. Tanimoto recalled, “I started walking to Mr. Matsuo’s house.” There, as both he and Matsuo later recounted, he found that their burden was to carry a tansu, what he described to me as a large Japanese cabinet, full of clothing and household goods. The two men set out. Newspapers from the day tell us that the morning was perfectly clear and so warm that both men felt that the day promised to be uncomfortable. A few minutes after they started, the air-raid siren went off, at what the Japanese government later said was 8:44 AM —a minute-long blast that, many residents later testified, warned of approaching planes but usually indicated to the people of Hiroshima only a slight degree of danger, since it sound every morning at this time, commonly when an American weather plane came over. U.S. military commanders later confirmed that these were, in fact, spying runs.(4)

You may, yourself, notice many differences here. To my eye and ear, Hersey’s own prose, in the original first version I’ve given you here, seems less cluttered, more compact—a simple word count tells us that. Many of Hersey’s stylistic choices often tend toward this restrained, compressed, seemingly straight factual effect. And even though his original is in the past tense, his prose seems intent on creating that feeling of immediacy I myself responded to on my first reading when I was a teenager. That is, we might feel, as I first did, that the effect of removing such attributions is to make readers believe that they are listening directly, as if it’s a reality effect we all recognize, that famous “fly on the wall” effect (or fourth wall effect if this were drama) that enhances the feeling of immediacy. (Some will label this the illusion of unmediated experience, to tell us that the media representative, the recording journalist, has been made to disappear. Or, again, to make it seem Archimedean.)

So one way to think of those passages is that Hersey consciously omitted those attributions–in order to make the moment seem “real.”

But if you really think about it, you can see that the effect of Hersey’s choice to remove attribution, above, is actually more complicated than all that. For instance, though we may feel we’ve been listening to directly quoted dialogue, maybe we’re not: rather, maybe Hersey has translated such interviews into actions and indirect descriptions, again to make us feel as if we’re reading a transcription of what happened. Moreover, my added attributions might have actually served to clear up things that Hersey doesn’t bother to clarify: about who said what and where.

And so, you see, there might be an argument worth taking on about which is really more “realistic.” Paradoxically, for instance—and many mainstream reporters would agree with me on this—adding the attributions actually makes the passage more authoritative even if it also might seem less realistic in the way we commonly use the word. (You might want to read that sentence again). In fact, you can imagine (and, as I’ve said, you should imagine) journalistic subjects objecting to having the context of their words removed. Many, in fact, do. In fact, if you want to really get down into the grammatical weeds, one thing a rhetorician or grammarian might say is that my added attributions also have what is called restrictive effects—that is, they may limit the authority and even the power of a given fact by showing us a source for it that we might actually find insufficient or unpersuasive. So, for instance, if we learn that Hersey is using a photograph to describe a character rather than standing there looking at him, that might actually be less authoritative that Hersey made it seem, since photographs can be staged, or add weight to the person being photographed, and so on. And as such, we might realize that things Hersey does not attribute look like pure or incontestable facts rather than something said or claimed by a third party or source.

Now, it’s important to say again that I’ve made those missing attributions up. And there’s little evidence that Hersey did anything immoral or unethical here–and no evidence, here, that he was inventing facts. Nevertheless, we can say that if he enhances the reality effect of what we read, perhaps he did so by covering his tracks or “footprints.” And with such disagreements, one starts to see what could be the basis of your own critique. Indeed, some controversy.

Reality Effect #2: Point of View

Then there is the matter of point of view. We all have had the infamous list of this technique drilled into us in secondary school and college (first person, third person, omniscient, third person limited, and so on). For works of narrative journalism, however, I often think it’s more useful to think about point of view quite literally: as a term for the vantage point from which events are seen. Again, as in a painting. Even when removing attributions obscure the original telling occasion, it’s still the case that point of view can imply a position from which things are seen—even, for instance, create the effect of interior thoughts or feelings on the part of characters.

For instance, we often say long-form journalistic reporters typically use a mix of the “first” and “third” person. But in fact, much of realistic reportage resorts to what is more precisely called, in fiction, free indirect discourse—simply put, a stylistic effect in which the narration of time, action, place and so on crosses back and forth from a third person narrator and the interior thoughts and/or feelings of specific characters.

Take this passage from Alex Kotlowitz’s account of two boys named Lafayette and Pharaoh Rivers (not their real names) growing up in a housing project in Chicago in the late 1980s. By and large, There Are No Children Here uses what for a novel we would call a past-tense omniscient narrator. That is, in his story-form, Kotlowitz chose to make himself invisible to the story he tells us, preferring instead to keep us focused on the boys themselves and their experience. Below is a scene where the boys and their mother, LaJoe, take a rare visit to the glamorous downtown high-rises and shops during the Christmas holiday season. Before this passage, Kotlowitz has been describing the children’s excitement in his own narrative voice, but then he shifts into the mother Lajoe’s consciousness, thoughts, and memories:

LaJoe began to share in their excitement. “When we’re through,” she promised the distracted crew, “I’ll buy you some popcorn like you’ve never tasted before.” She remembered the popcorn her mother treated her to when as a young girl she had visited her at her job in the downtown county building. LaJoe was beginning to feel a part of an ordinary family, a family without problems. . . .

Then, Kotlowitz shifts into the head of one of her boys named Pharoah, then out again into third person, from free indirect discourse into something like a literary voice:

. . . Pharaoh was mesmerized by the afternoon rush. Men in suits and ties walked past him, their eyes focused straight ahead, their faces fixed with determination. And the women. They looked so pretty in their long wool coats, brightly colored scarves draped around their rosy faces. He twirled 180 degrees as his gaze followed one passerby after another.

“Pharaoh!” LaJoe shouted again. “Pharaoh!” He drew upright at the sound of his name, which for the past minute had fluttered by him like the rush-hour shoppers . . . .Like paper chains, the eight of them floated down State Street… (173)

Despite all the shifts in point of view here, one of my students a few years ago called Kotlowitz’s style of realism “seamless,” and I think she was really onto something. Because of those shifts, it’s almost as if there is no seam, no gap, between Kotlowitz’s narrative voice and what LaJoe or Pharaoh thinks or feels. We skip from consciousness to consciousness, while the boy’s fascination or the mother’s worries can be reflected in ours.

Naturally, this technique can raise hackles for some readers and writers: how can a journalist claim to be inside someone’s head? (As I said in Chapter 1, even some very famous narrative journalists say you shouldn’t ever do this.) Or, again, what about the problem of attribution or verification—what are the sources, we may wonder, for what a certain character is said to have thought? All, as I’ve said, reasonable questions, and points worth disputing. But for now, I think, it’s important to see how this effect is created and what its interpretive consequences are. After all, even in moments we hear an interior voice for Pharaoh, quite often the diction tells us that it is really Kotlowitz’s voice (e.g. when he uses “the paper chains” analogy).

To put this another way, free indirect discourse, in many moments, makes it seem as if the narrator (journalist) and character (especially LaJoe, above) share or co-create a common interior language for explaining what’s happening to the characters. And, indeed, Kotlowitz re-voices a feeling that he says LaJoe has: that she wants to feel, for the moment, that she has a normal family. In another phase of that same passage, Kotlowitz interpolates a description Pharoah might have used (“so pretty”), and we can’t separate the two. But that’s the point: scholars of the 19th century novel tradition of social realism upon which Kotlowitz draws, in fact, call this a consensual effect, in that the realism of the scene is created by the way the master narrator seems to gather up his characters’ views into a reality we are asked to agree upon, ourselves. In other words, the style signals to use that the writer is right in there with them, intuiting their desires and hopes and—more to the point—sharing in them. And naturally, that’s why I encourage you to also think of the subjects independently, if you can: what would they make of that sharing?

Reality Effect #3: Retrospection

This kind of consensual effect is also illustrated by a third, less-discussed and perhaps even more controversial stylistic technique in narrative journalism. And that is the customary use of retrospection in the narrative voice. Though we barely recognize it as such, like many classic novels, reportage is customarily told in the past tense: when someone testifies in the text, for instance, the journalist will write “he (or she) “…said,” not “says.” But what we often don’t recognize is that, as narration, this is a past tense that has been created by an author or narrator who is actually speaking in our own (the reader’s) present tense. Thus, the writer might be best understood as standing at the very end of the book, looking back and telling us what happened. Let’s see if the following graphic illustrations help:

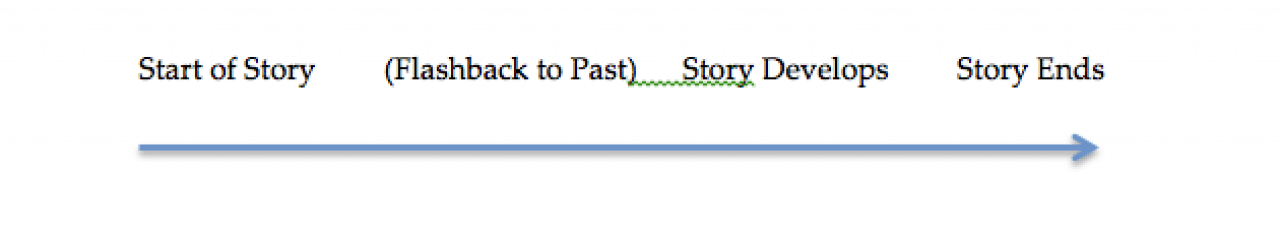

We commonly read a story from start to finish, and the author may include what we colloquially call flashbacks to prior events. So a graph of the narrative might look like this:

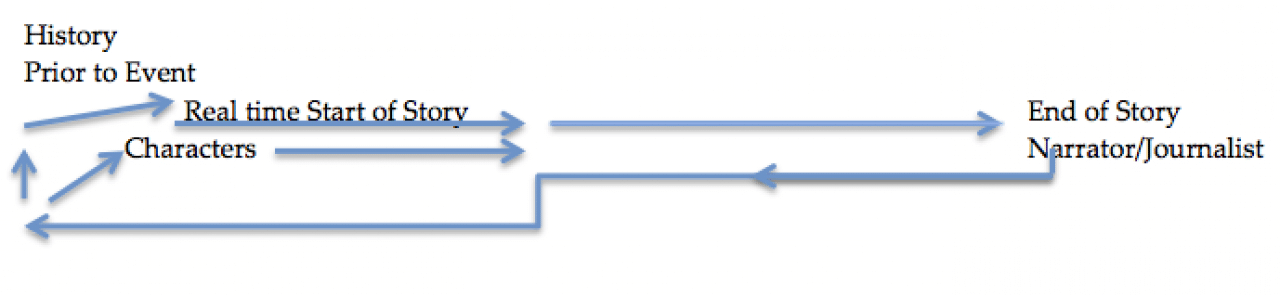

In real time, however, the journalist commonly comes to writing the story we’re reading after it has already finished. So if you were thinking of this in real-time, the writer actually “stands” at the right end of this graph, not the left, and is looking backwards in time, and then moving forward back to the present:

This would be true, in fact, even if in real time the reporter arrived in the middle of the story—writing it up habitually starts after everything is concluded. This is why, in fact, attribution is typically in the past tense (“he said”)—because it always happened before the writer is telling us that it did.

Well, so what?

Well, of course there are tremendous interpretive and story-telling advantages to hindsight: looking back on events, we often think we can now see where things were headed. And thus, in the reality-effects of novels and much of narrative nonfiction, the narrator gets the privilege of putting into the past tense those things that the reporter could really only know later, in hindsight. Omniscience, something that is only possible in narrative (and not in real life), is thus linked to a certain power over time. Indeed, what we habitually call fictional foreshadowing in introductory literature courses is, especially in narrative journalism, actually narrative hindsight. And that’s especially important for reportage—and, legitimately controversial–because such a position of foreknowledge was often not present in the moment at all. Even if one couldn’t know then, the reality effect of retrospection makes it seem as if one could know. And the big risk such retrospection runs, of course, is that it creates a position of viewing, of knowing, that no one (not even the reporter) experienced in real time.

Even, alas, if a report looks realistic. And so, it’s perfectly legitimate to push back, to question: how much of such foresight was possible, for instance, in the real time of the people being depicted? Are they being faulted for not being able to foresee what the narrator only knows by virtue of hindsight?

Some Takeaways about Style and Selection

You might have already intuited my first takeaway:

1. The question is usually not whether a given work of narrative journalism is realistic—many of them are. Rather, the question should be how it achieves such an effect on us, if it does. Therefore, we need to try and distinguish what is a byproduct of witnessing, or experiential immersion, or testimony from characters or a reporter, and what is an effect of literary technique.

Realism comes in different packages, of course. And as a result, there are different ways that we can become involved, much as a camera eye in a documentary can create different engagements in us: the awe and power we might feel in a panoramic shot that sweeps across a city; the exhilaration of being lifted up off the planet, allowed to see a Hurricane from space, while before (as in, say, Zeitoun, we have been paddling around in a canoe).

Or, think of the way a camera close up has the counter-effect of blocking out what is surrounding a face: yes, we may think we see intimate reactions and emotions, but we might be missing what’s actually causing them.

But as we describe these stylistic effects, we also need to break their spell over us, perhaps by asking questions of the selections and techniques used that seem to ask us to see the reporter as “in with” his subjects, sharing their dreams, and so on. Here again, thinking about the subject’s dimension, their story and how it might be told, is worth considering. Sometimes you even find a discrepancy between what a narrator offers up and what a character actually says. And for instance, if Alex Kotlowitz’s omniscience is only an effect of style and retrospection, what might he see?—or have seen– in real time? In No Children, for example, it’s easy to forget, while we’re watching LaJoe, Pharoah and Lafayette that there are liable to be six or eight or even ten more people in the apartment with them, or that Kotlowitz himself might be one of them. What effect do you think that might have had? Why choose these two boys, and not their older siblings, or their neighbors?

Hersey’s canvas, by contrast, works largely by omission, rigorously restricting itself to what its six characters can know and don’t know about the bomb’s power or meaning. The rationales for the U.S. dropping the Bomb, by Harry Truman or others, go largely if not totally unmentioned in the book. But that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t wonder or ask about such rationales. In my view, Hersey is not, in fact, creating an effect where we’re the proverbial “fly on the wall.” Instead, that testimony (which was, we should remember, originally in Japanese) has been filtered back through Hersey’s voice, in some cases muted in very complicated ways. I worry that we can’t always figure out, in fact, whether Hersey’s characters are or have been traumatized, or whether the journalist is simply using Hemingwayesque omission to make us feel, paradoxically, the power of the things about the Bomb that can’t be named. But as with Kotlowitz, we should interrogate or question those stylistic choices. Can an American’s English transpose Japanese language and culture, and what might be lost in translation? Does the stoic Hemingway style make us feel the power of the bomb, or does it mute its horrors? Does Hersey’s narrator seem to make common cause with his Japanese subjects, and what kinds of cultural differences or gaps might that reality effect disguise?

In other words, there is an important qualification on my suggestion here about focusing on style, and it’s my second takeaway:

2. Matters of style and selection really can’t be separated from the interpretive work of a given work of narrative journalism: rather, they tell us how a journalist interprets the events they report on.

To understand another analogy to a photograph’s cropping, for instance, one might take the matter of how a journalist picks the ending for his book. In No Children, Kotlowitz chooses to end his book right at the moment one of those brothers has his criminal case dismissed—and well before his younger brother has become fully aware of the hard choices (for example, about joining a gang) ahead of him. Obviously, these boys’ lives continued on. But the key point here is that Kotlowitz’s ending was strategic: he ended his story-form as the boys were still children, compelling his reader to worry about their future. Or, take the decision about whom to talk to. Kotlowitz spent over six years developing his relationship with those boys and their mother, drawing close to their daily lives and their dreams. Kotlowitz depicts gang violence and membership, as I’ve suggested, as the primary threat to those boys as they grow up. But as I’ve just suggested, we never actually see what it’s like to be inside a gang, in part because the book ends before his subjects even join one. Though Kotlowitz of course can offer others’ research on gang life, interview the police and a gang member (perhaps one in prison), and so on, his horizon line stays largely around the subjects he has chosen. And that, for all the achievements of the book, may limit its angle of vision.

The same analogy to photographic cropping, meanwhile, might be applied to Hiroshima, in fact. As I’ve said, strategic decisions made by the U.S.—considerations that, as I’ve said, made the Bomb the opening blow of the Cold War—are left almost entirely out of view in Hersey’s telling, in favor of the experience (and as I’ve suggested, the memories) of his six victims. But you might notice that, strictly speaking, these are Bomb survivors—certainly those immediately killed were affected by the Bomb, but we’re not reading about them.3 And should we know or be told about the strategic considerations of the U.S. in dropping the Bomb? Some have complained that leaving these matters unsaid leaves them unexamined, too.

And thus, one final takeaway:

3. Whenever possible, the story-form of a given work of narrative journalism is best tested against those other dimensions of “the story” I mentioned in Chapter 2, and even against counterfactuals we can conjure up, ourselves.

In much of the above, I’m trying to suggest how important style and selection are for effects of realism. Quite often, however, they also testify to how a journalist wants you to understand the legwork and subject relations behind a given narrative. From effects of style and selection, we can often infer subject relations (a third dimension in Chapters 1 and 2), even fill in seemingly missing attributions, because nearly always these choices reflect decisions to see things from a particular point of view. Thus, these styles are meant to testify to the kind of commitment each writer made to trying to see from his subjects’ points of view, and indeed to model a certain relationship that made the reporting possible in the first place. Hersey’s indirect transposition of his subjects’ experience, his refusal to offer retrospective knowledge, is designed in part to cede some authority to his subjects, to let them speak to the Bomb’s meaning, and in particular to speak to readers in the language of those who dropped it.

However, don’t hesitate to fill in material that might have originally contributed to the creation of a different work of narrative journalism with some of the same “givens.” As I’ve said, if Kotlowitz’s book is focused on two boys in a ghetto— what, then, if this were a book about two young girls? Likewise, what is in or beyond Chicago that can’t be seen by them, that might be affecting those boys? What if they were Hispanic or white?—how would that change the substance of the story? What if Kotlowitz was not invisible to us—suppose we saw him, notebook in hand, in the Rivers’ apartment? And in regard Hersey, what if he wrote a Preface where he told us why he chose his six characters, and not six others? What if he did include Harry Truman’s calculations about the costs of not dropping the bomb, or why the President chose Hiroshima and not, as historians have debated, some other more strategic city?

Some historians and literary critics have a word for these kinds of speculations, and it’s a word they sometimes use pejoratively: they are sometimes called counterfactuals, or counterfactual speculations. For readers of narrative journalism, I believe it means you sometimes have to be willing to think outside the frame, to entertain facts that haven’t been selected or scenes unwritten—because if you do, you actually get close to heart of the spell of realism in reportage. You recognize its power, and something equally as important: your own power to break free of its interpretation, and offer up your own.

And it turns out there’s a lot more to style–and that’s what the next two Chapters of this site are about. My two main examples in this chapter, for example, represent very different ways of seeming realistic. Hersey’s style is much more influenced by what is sometimes called modernist realism, of the kind modeled by Ernest Hemingway and, in Hersey’s case, Thornton Wilder (especially Wilder’s novel the Bridge at San Luis Rey [1927], about six people killed in a Peruvian bridge accident). Kotlowitz’s There Are No Children Here draws upon the template style of the 18th and 19th century social-realist novel. Particularly in the moment when it is offering up a sentimental plea for these two boys’ dignity and future, he sounds an awful lot like Charles Dickens. (On that Christmas trip to the downtown in Kotlowitz’s book, Dickens is explicitly mentioned, and there’s even, yes, a tiny character named Tim we meet along the way).

The next Chapter takes up that element: the moment when a narrative journalist reaches out to select a particular Genre of writing.

A Study Sheet on Realism in Narrative Journalism

Notes

- Barthes, Roland. “The Reality Effect.” The Rustle of Language, Trans. Richard Howard. Oxford: Blackwell, 1986. 141-148. ↩︎

- Yerkes, Andrew C. “’A Biology of Dictatorships”: Liberalism and Realism in Sinclair Lewis’s It Can’t Happen Here,” Studies in the Novel 42 (2010), 3. ↩︎

- In fact, leaving aside how the Japanese have responded to Hersey’s rendering, there is an entire strand of American criticism that has said that Hiroshima really isn’t realistic enough: that is, that these effects actually mute the bomb’s horror. Readers disagree, that is, over the interpretation of the Bomb resulting from Hersey’s style and selections. See esp. the commentaries of Dwight MacDonald, “John Hersey’s ‘Hiroshima,’” Politics 3:10:308 (Oct 1946), and Mary McCarthy’s Letter to the Editor, also in Politics 3:10: 367 (Nov. 1946). Cf. also Phyllis Frus, The Politics and Poetics of Journalistic Narrative (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994). ↩︎